Interview with Nicolas Champeaux and Gilles Porte

The journalist Nicolas Champeaux and the filmmaker Gilles Porte plunged into the archives of the Rivonia Trial, which resulted in June 1964 in Nelson Mandela and seven others being sentenced to life imprisonment. Presented in a Special Screening, The State Against Mandela And The Others reminds us of how important the role was of Mandela's co-defendants in the witness box, although unknown to the general public, in the legal battle against Apartheid.

How did the film come about?

Nicolas Champeaux: I had the chance to interview some of the defendants who were sentenced alongside Nelson Mandela when I was a sent as a special correspondent to Johannesburg. Two years ago, I obtained exclusive access to the sound archives of the Rivonia trial and what I heard really shook me. In the spring of 2016 I decided to construct a film based on those tapes.

Why revisit the trial?

NC: I wanted to tell the story of Mandela's comrades. They were black, white and Indian, and like him, they paid a heavy price, but remained in the shadows. I wanted to give these voices unknown to the general public a platform, on an equal footing with Nelson Mandela, who is the only one to have really been in the limelight.

Gilles Porte: At the beginning, we wanted to call this film "The Others". They were the ones who made Mandela what he was. Their movement needed a face and Mandela was chosen because he'd studied and knew how to talk. The iconic Mandela figure arose out of that.

What struck you most when listening to the archives?

NC: I was impressed by their courage and their mental agility in turning every situation round. They were all in a deeply uncomfortable situation as they potentially faced the death penalty. But they preferred to sacrifice their lives, faced with a racist cartoon prosecutor, in order to defend their cause. During the counter-interrogations, they described how they had come to this level of activism and told their personal stories. It's very moving, and that's what we've restored in the film.

How did you prepare it?

NC: We first listened to the entire archives, around 256 hours, and made a selection. We then went to meet five protagonists who are still alive – three of the defendants and two lawyers – all now in their nineties, and we conducted marathon four-to-five hour interviews. We offered them the chance to listen to the sound extracts, which they had never heard. They were all extremely responsive and curious about it, fifty years on. And we see the survivors listening to and reacting to the archives.

When did the structure of the film make itself clear to you?

NC: We quickly established a framework but the interviews we carried out changed that. We made two shoots twelve months apart. In between, we refined the screenplay on the basis of the information we'd gathered.

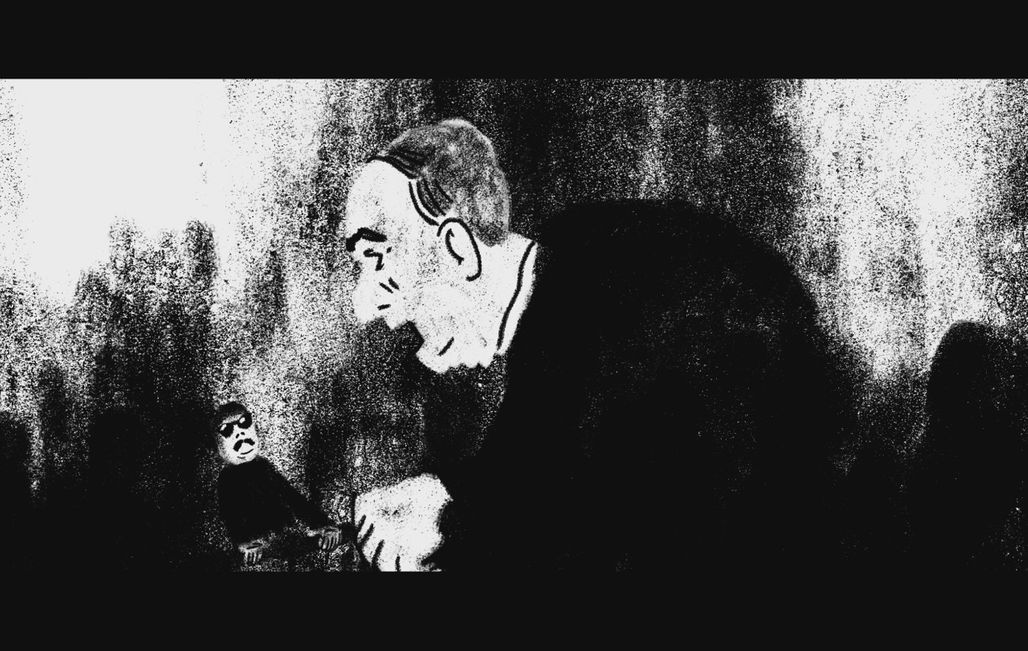

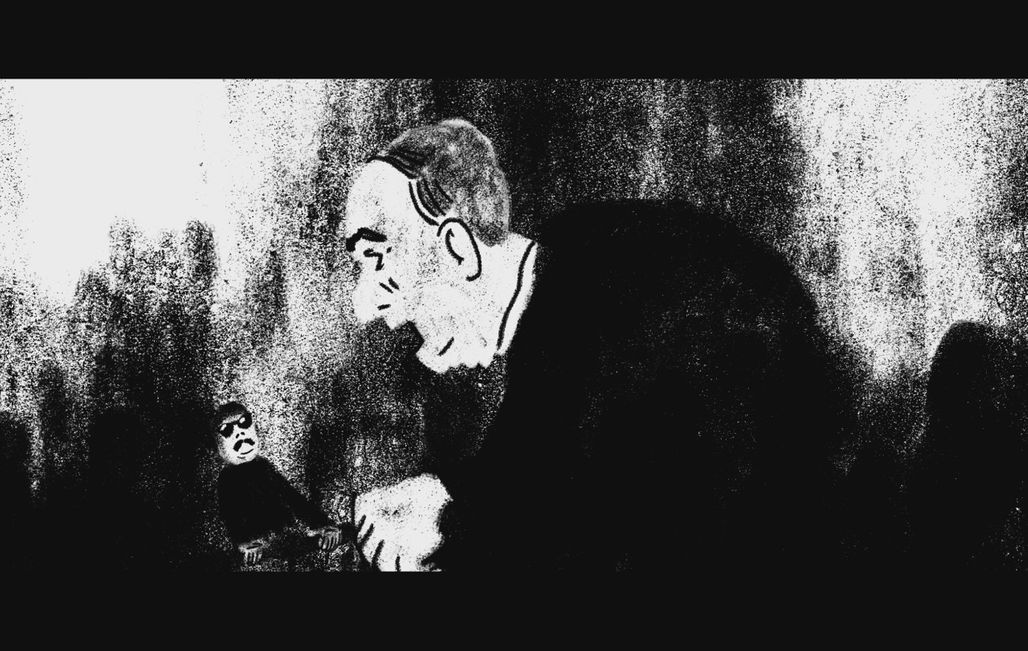

You illustrate the film with animation. Why is that?

GP: I asked to see the drawings of the trial, and very quickly came across the drawings of the wife of one of the co-defendants. She sat through the hearings and sketched all the protagonists. Her initiative inspired me. I called on one of the graphic designers I'd worked with before and I introduced him to Nicolas, In total, the film contains 40 minutes of animation.

How did you work with the archives?

NC: They were good quality but we proceeded to restore them. The film contains over 35 minutes of sound archives. The challenge was not to let the animation, either abstract or figurative, distract the spectator from what was going on in the trial.

GP: We wanted to give the protagonists' voices centre stage and at the same time make sure the music and sounds didn't upstage the archives, or the words of the defendants – in some cases their last words. That meant we had to work meticulously on the sound.