CANNES AND RUSSIA: A LOVE-HATE RELATIONSHIP

BY JOEL CHAPRON *

“Crown an American, and you have sold yourself to the US; crown a Russian, and you are a Communist”, Cocteau used to say, and he knew what he was talking about, having served twice as President of the Jury and once as Honorary President of the Festival de Cannes. Of all countries, the Soviet Union was the one to experience the most political turmoil over its presence – and absences – at the Festival. Over the first twenty-five years, when countries submitted their own films, relations changed according to the political reversals in the two countries, with the Festival serving as a major issue in these relations.

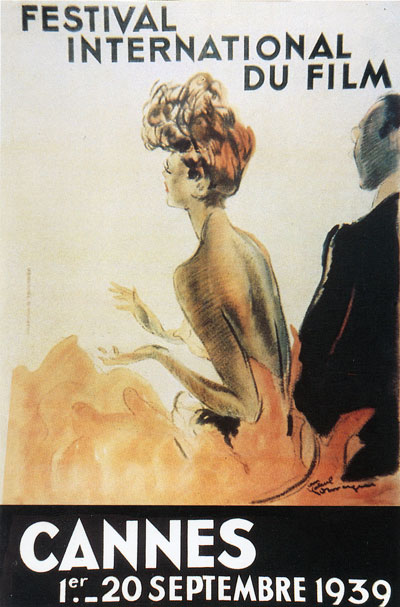

Solicited via diplomatic channels like all the other countries, the Soviet Union was invited to the first Festival de Cannes in  1939. For obvious political reasons, France coveted the participation of the USSR, hoping to make them an ally. On 13 August 1939, Vyacheslav Molotov, Chairman of the Council of People’s Commissars, signed a secret note addressed to the Politburo in which he named “Comrade Kormilitsin, Chief of the USSR’s commercial delegation in France, as a member of the jury at the Festival de Cannes and Comrade Polonski, director of Mosfilm studios, as the representative of Soviet cinematography”. Two days later, the Politburo approved the decision and the USSR, responding to the special privileges that France extended to them concerning the number of films presented, selected four feature films and four short films. However, on 23rd August, this same Molotov signed the Nazi-Soviet non-aggression pact with Joachim von Ribbentrop, Hitler’s representative. French hopes were dashed, war was declared and the Festival was cancelled – Kormilitsin was never to serve on the jury.

1939. For obvious political reasons, France coveted the participation of the USSR, hoping to make them an ally. On 13 August 1939, Vyacheslav Molotov, Chairman of the Council of People’s Commissars, signed a secret note addressed to the Politburo in which he named “Comrade Kormilitsin, Chief of the USSR’s commercial delegation in France, as a member of the jury at the Festival de Cannes and Comrade Polonski, director of Mosfilm studios, as the representative of Soviet cinematography”. Two days later, the Politburo approved the decision and the USSR, responding to the special privileges that France extended to them concerning the number of films presented, selected four feature films and four short films. However, on 23rd August, this same Molotov signed the Nazi-Soviet non-aggression pact with Joachim von Ribbentrop, Hitler’s representative. French hopes were dashed, war was declared and the Festival was cancelled – Kormilitsin was never to serve on the jury.

In September 1946, in preparation for the first Festival that actually took place, France made it a priority to invite the victorious nations, including, of course, the USSR. During this Festival, the Soviet delegation became famous for its receptions, where guests could help themselves to as much caviar and vodka as they liked (a tradition that was maintained until Perestroika), but where they had to wear a little red flag with the slogan “Art in the service of peace” in their buttonholes. Nevertheless, in light of the technical problems that occurred during the screening of their films (and for other reasons as well), the Soviets claimed they were the victims of sabotage and began a long series of paranoid protests that the Festival would have to deal with over the next four decades. In 1949, the Party’s Central Committee decided that the USSR would not participate in the Festival on the grounds that they were discriminated against by the rule that set a quota for the number of films to be presented by each country in proportion to that country’s annual production, which of course reserved the lion’s share for America. The Soviets did not return to the Festival until two years later, after Stalin himself gave his approval. The Soviets sent seven films to the Festival, accompanied by the director Vsevolod Pudovkin and the actor Nikolai Cherkasov, who had become famous in his roles as Alexander Nevsky and Ivan the Terrible in films directed by Eisenstein. However, the Soviet-Chinese documentary The New China, by Sergei Gerasimov, was withdrawn from the competition by the Festival itself under pressure from the French government, who did not want to “offend national sentiment” (as is provided for by one of the Festival’s regulations) of other countries that only recognised Formosa (Taiwan) and not Maoist China. The offended Soviets boycotted the 1952 and 1953 Festival seasons, to return in 1954, after the death of Stalin (with 120 kilos of caviar in their baggage for their famous reception!). In turn, they lodged a complaint against a Swedish film for “offence to national sentiment”.

that the USSR would not participate in the Festival on the grounds that they were discriminated against by the rule that set a quota for the number of films to be presented by each country in proportion to that country’s annual production, which of course reserved the lion’s share for America. The Soviets did not return to the Festival until two years later, after Stalin himself gave his approval. The Soviets sent seven films to the Festival, accompanied by the director Vsevolod Pudovkin and the actor Nikolai Cherkasov, who had become famous in his roles as Alexander Nevsky and Ivan the Terrible in films directed by Eisenstein. However, the Soviet-Chinese documentary The New China, by Sergei Gerasimov, was withdrawn from the competition by the Festival itself under pressure from the French government, who did not want to “offend national sentiment” (as is provided for by one of the Festival’s regulations) of other countries that only recognised Formosa (Taiwan) and not Maoist China. The offended Soviets boycotted the 1952 and 1953 Festival seasons, to return in 1954, after the death of Stalin (with 120 kilos of caviar in their baggage for their famous reception!). In turn, they lodged a complaint against a Swedish film for “offence to national sentiment”.

In 1955, Soviet films won five awards in all (for the first time, a Soviet filmmaker, Sergei Yutkevitch, was on the jury). However, 1958 was the banner year. In the midst of the political “thaw”, Mikhail Kalatozov won the Palme d’Or – the only one in the history of Russian cinema to date – with Letjat Zuravli (The Cranes are Flying).

|

This beautiful and moving film, a testimony to the Soviet revival, presents the fateful turns of an unhappy love affair in the dramatic context of the war. The film introduced two extraordinary actors, Tatiana Samoilova and Alexei Batalov, as well as a virtuoso of cinematography, Sergei Urussevski. With the advent of the 1960s, the Festival was still under the yoke of French politics – Gaullist politics this time around. It snubbed both Soviet and American cinematography, giving precedence to European films which, as a result, carried off most of the awards. Nevertheless, the Soviet films selected over the years by the Central Committee to represent the country did receive all kinds of Special Jury awards: “Best Lyric Film” (1955),  “Best Original Screenplay, Human Quality and Novelistic Grandeur” (The Forty-First by G. Chukhrai, 1957), “Best Participation” (1960), “Best Depiction of a Revolutionary Epic” (1963), but also, fortunately, “Best Director” (1956, 1961 and 1966). Whenever they did not receive any awards (1964), vehement protests appeared in the Soviet press, to which the French government responded through diplomatic channels to calm things down. In 1966, Robert Favre Le Bret, the general delegate at the time, travelled to the USSR and subsequently the State Cinematography Committee and the Union of Soviet Filmmakers revealed, in a secret letter to the Central Committee, that he had given them to understand that David Lean’s Doctor Zhivago would open the Festival. Both of these Soviet institutions felt, therefore, that participation was not advisable. However, they finally declared that the embassy of the USSR in Paris “had taken steps to ensure that this film would not open the Festival” (in June, de Gaulle had to go to Moscow and this visit led to the signing of an agreement on Franco-Soviet cinematographic coo

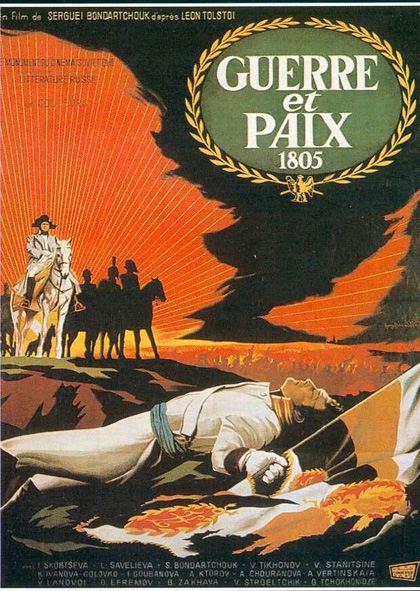

“Best Original Screenplay, Human Quality and Novelistic Grandeur” (The Forty-First by G. Chukhrai, 1957), “Best Participation” (1960), “Best Depiction of a Revolutionary Epic” (1963), but also, fortunately, “Best Director” (1956, 1961 and 1966). Whenever they did not receive any awards (1964), vehement protests appeared in the Soviet press, to which the French government responded through diplomatic channels to calm things down. In 1966, Robert Favre Le Bret, the general delegate at the time, travelled to the USSR and subsequently the State Cinematography Committee and the Union of Soviet Filmmakers revealed, in a secret letter to the Central Committee, that he had given them to understand that David Lean’s Doctor Zhivago would open the Festival. Both of these Soviet institutions felt, therefore, that participation was not advisable. However, they finally declared that the embassy of the USSR in Paris “had taken steps to ensure that this film would not open the Festival” (in June, de Gaulle had to go to Moscow and this visit led to the signing of an agreement on Franco-Soviet cinematographic coo peration in July of 1967). As a result, Soviet films were able to participate. In 1967, journalists asked the Soviet delegation in attendance at Sergei Bondarchuk’s press conference for War and Peace why Tarkovsky’s Andrei Roublev was not at the Festival, to which the Director of Mosfilm responded that the film was not ready – which was not true. It was sold to France in 1969 and presented at the Festival that same year by the company that bought it (Out of Competition and without the approval of the Soviet Committee of Cinematography). It won the FIPRESCI Critics’ Award (which the authorities urged Tarkovsky to refuse, as the President of the French Critics’ Union was considered to be Zionist; the Central Committee issued a severe reprimand to the Ministry of Cinema for the error committed).

peration in July of 1967). As a result, Soviet films were able to participate. In 1967, journalists asked the Soviet delegation in attendance at Sergei Bondarchuk’s press conference for War and Peace why Tarkovsky’s Andrei Roublev was not at the Festival, to which the Director of Mosfilm responded that the film was not ready – which was not true. It was sold to France in 1969 and presented at the Festival that same year by the company that bought it (Out of Competition and without the approval of the Soviet Committee of Cinematography). It won the FIPRESCI Critics’ Award (which the authorities urged Tarkovsky to refuse, as the President of the French Critics’ Union was considered to be Zionist; the Central Committee issued a severe reprimand to the Ministry of Cinema for the error committed).

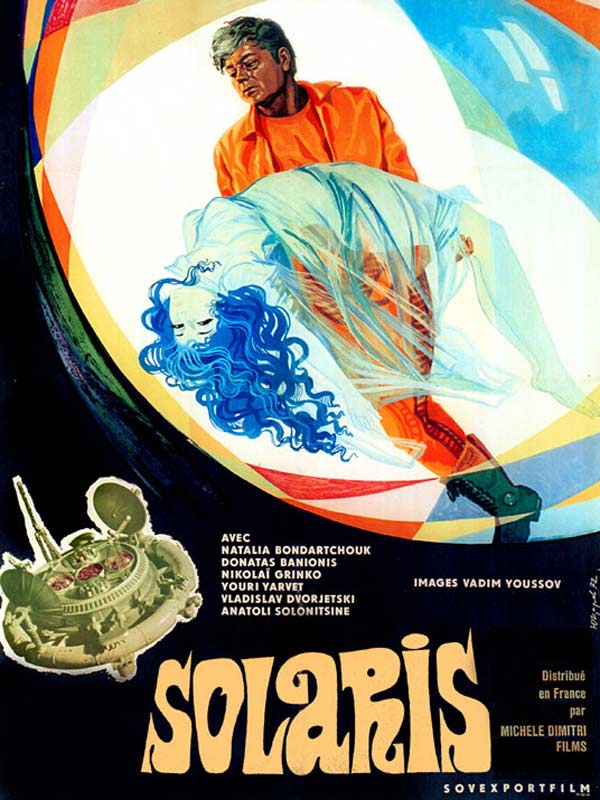

1968 marked a major shift in mentality and by the end of the sixties, the Festival enjoyed greater freedom. This hardly pleased the Soviets, who balked at submitting films to the new section created in 1969, the Directors’ Fortnight. Before Perestroika, the only hard-won screenings of Soviet films in the Directors’ Fortnight were  There Once was a Singing Blackbird, by losseliani (who came under escort) in 1974, Mikhalkov’s Five Evenings in 1979 and, in 1985, Gouloubye Gory (The Blue Mountains) by Chenguelaia – who was not informed in advance of the selection by the Soviet ministry, only learning of it three months later – as well as a short film by Parazhanov, Return to Life, which the Directors’ Fortnight screened secretly in 1980. In 1970, the USSR was absent from the Festival but returned in 1971 with a film that was initially refused by the Festival before being later accepted. The same scenario took place in 1976, but the Festival upheld its decision. In fact, since 1972, it is the Festival that chooses the films, not the country from which they originate (even if, as in 1975, diplomatic pressures may win the day). Relations immediately soured as a result and the USSR balked at handing over the films that the General Delegates requested. So was it based on a misunderstanding that Tarkovsky won the Special Jury Grand Prix for Solaris, screened in his presence in 1972? In fact, the interpreter for the Soviet jury member, who had emigrated to France long before, did not understand everything that Mark Donskoy said!

There Once was a Singing Blackbird, by losseliani (who came under escort) in 1974, Mikhalkov’s Five Evenings in 1979 and, in 1985, Gouloubye Gory (The Blue Mountains) by Chenguelaia – who was not informed in advance of the selection by the Soviet ministry, only learning of it three months later – as well as a short film by Parazhanov, Return to Life, which the Directors’ Fortnight screened secretly in 1980. In 1970, the USSR was absent from the Festival but returned in 1971 with a film that was initially refused by the Festival before being later accepted. The same scenario took place in 1976, but the Festival upheld its decision. In fact, since 1972, it is the Festival that chooses the films, not the country from which they originate (even if, as in 1975, diplomatic pressures may win the day). Relations immediately soured as a result and the USSR balked at handing over the films that the General Delegates requested. So was it based on a misunderstanding that Tarkovsky won the Special Jury Grand Prix for Solaris, screened in his presence in 1972? In fact, the interpreter for the Soviet jury member, who had emigrated to France long before, did not understand everything that Mark Donskoy said!

|

Mikhalkov came to Cannes for the first time in 1977 with An Unfinished Piece for Player Piano, but Out of Competition. During his first trip to the USSR, Gilles Jacob, to whom Maurice Bessy, General Delegate since 1972, was handing over the responsibility for selection, wanted to see Iosseliani’s Pastorale, but the Cinematography Committee did not allow him to do so. Gilles Jacob had to ply his course between two opposing positions. On the one hand, Robert Favre Le Bret, who had become President of the Festival, had developed affinities with the USSR. On the other hand, Maurice Bessy held a very firm position regarding this country that demanded a greater presence for its films in Cannes but which the Minister for Cinema considered as “not very significant”. In 1979, the Soviets refused to send Stalker to Cannes on the pretext that “the film is too good and [that they] are saving it for the Moscow Festival” – where of course, it was never screened! But the next year, Gilles Jacob  obtained a copy illegally through subterfuge, which he screened without announcing it as a “surprise programme”. The Soviets were up in arms, but the screening took place and the film received the Prize of the Ecumenical Jury. In 1983, Tarkovsky was in Cannes with Nostalghia and Bondarchuk was on the jury, and even though the latter spent his time denigrating the former’s film, it carried off three awards. Backstage, Tarkovsky bumped into Andrei Konchalovsky, his old friend and co-screenwriter of Andrei Roublev, with whom he had broken off relations. Bondarchuk and Tarkovsky found themselves in competition against one another three years later. Tarkovsky, weakened by illness, did not come to Cannes, but he was awarded another three prizes, while Bondarchuk received nothing.

obtained a copy illegally through subterfuge, which he screened without announcing it as a “surprise programme”. The Soviets were up in arms, but the screening took place and the film received the Prize of the Ecumenical Jury. In 1983, Tarkovsky was in Cannes with Nostalghia and Bondarchuk was on the jury, and even though the latter spent his time denigrating the former’s film, it carried off three awards. Backstage, Tarkovsky bumped into Andrei Konchalovsky, his old friend and co-screenwriter of Andrei Roublev, with whom he had broken off relations. Bondarchuk and Tarkovsky found themselves in competition against one another three years later. Tarkovsky, weakened by illness, did not come to Cannes, but he was awarded another three prizes, while Bondarchuk received nothing.

Nostalghia directed by Andrei Tarkovski

Repentance directed by Tenguiz Abouladzé

Perestroika went on to change everything. Henceforth, the Festival was able to deal directly with the filmmakers themselves. The USSR was represented in competition, in 1987, by a key film of the new era that was coming into its own, Repentance by Tenguiz Abouladzé ( who had won the Palme d’Or for Short Films in 1956, the year of de-Stalinisation) and also, via Italy, by Mikhalkov’s Black Eyes (Oci ciornie). Yves Montand, President of the Jury, and Elem Klimov, a juror in the vanguard of Perestroika, were at odds over these two films (Montand was not convinced by the Communists’ “repentance”). Repentance was to leave with the Jury’s Special Grand Prix and Black Eyes with the award for Best Actor for Marcello Mastroianni. Ironically, Mikhalkov’s brother, Andrei Konchalovsky, was also in competition with an American film, Shy People, for which Barbara Hershey won the award for Best Actress. Finally, that same year, Nana Dzhordzhadze received the Caméra d’Or.

who had won the Palme d’Or for Short Films in 1956, the year of de-Stalinisation) and also, via Italy, by Mikhalkov’s Black Eyes (Oci ciornie). Yves Montand, President of the Jury, and Elem Klimov, a juror in the vanguard of Perestroika, were at odds over these two films (Montand was not convinced by the Communists’ “repentance”). Repentance was to leave with the Jury’s Special Grand Prix and Black Eyes with the award for Best Actor for Marcello Mastroianni. Ironically, Mikhalkov’s brother, Andrei Konchalovsky, was also in competition with an American film, Shy People, for which Barbara Hershey won the award for Best Actress. Finally, that same year, Nana Dzhordzhadze received the Caméra d’Or.

Robinsonnade, my English grandfather directed by Nana Djordjadzé

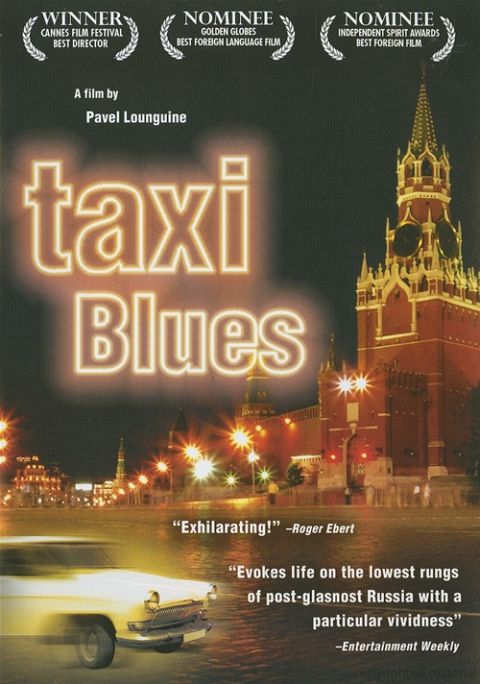

In 1990, this same prize was awarded to Vitali Kanevski, a 55-year old director who was presenting his first film. He arrived in Cannes as a hitchhiker, picked up by the sailors of a ship of the Soviet fleet anchored offshore. 1990 was also the year that the world discovered a new society in Pavel Lounguine’s Taxi Blues, where the old and new Soviet worlds confronted each other. The following year, the famous bad-boy director, Rustam Khamdamov, came to the competition with Anna Karamazoff, co-produced by French director Serge Silberman, with Jeanne Moreau in the lead role. Between Khamdamov and the French, who did not recognise the script they had agreed on in the film, sparks were flying even before the Festival opened. Silberman demanded an explanatory introduction; Khamdamov complied, but, at the press screening, his assistant placed his hand in front of the projector to prevent its being viewed. That evening, Jeanne Moreau was squirming in her seat; Silberman confiscated the film, saying he would never show it again (and, in fact, even after his death, it remains inaccessible).

Pavel Lounguine’s signature

Pavel Lounguine’s signature

Since the start of the 1990s, the scandals, intrigues and political blackmail related to Russian cinema have become a thing of the past. Russian cinematography has acquired its right to be treated like any other, which, in the eyes of some Russians, may sound like a step backwards. From that time, there were years in which no Soviet films were screened in competition (1995, 1996, 1997, 2004, 2005, 2006, 2008, 2009). Sometimes, the coveted Palme d’Or eluded the grasp of a hopeful contender: Mikhalkov left disappointed, in spite of his Grand Prix for Burnt by the Sun in 1994, and then he stammered on with Soleil Trompeur 2 in 2010). In a rare occurrence, a director in competition did not attend the Festival : this was the case of Sokurov in 2007, although he was the Russian director the most often selected in competition for twelve years. Five films out of the seven selected are his. Henceforth, in its selections and its non-selections, the Festival de Cannes has reflected the current state of Russian auteur cinema.

READ >>> THE HISTORY OF RUSSIAN CINEMA

* Joel Chapron works as a Russian interpreter and foreign correspondant at the Festival de Cannes. He is in charge of Central and Eastern European countries at Unifrance, Associate Lecturer at the University of Avignon, author of numerous articles on Eastern European cinema and editor of the new edition of the Dictionary of Film (Larousse).

The Festival de Cannes would like to thank all the writers for their free contributions.