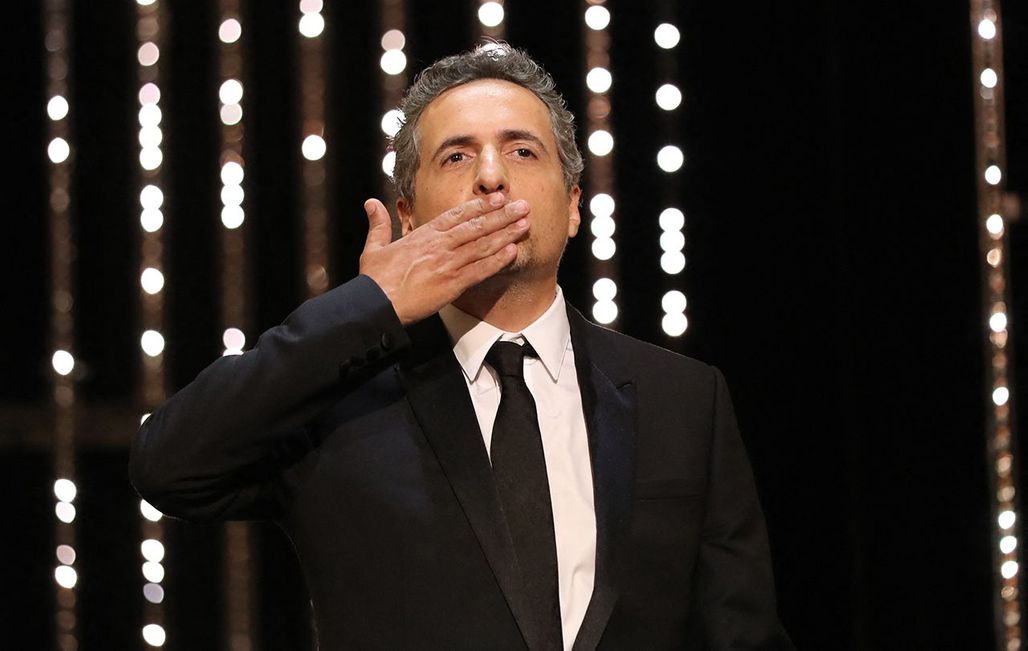

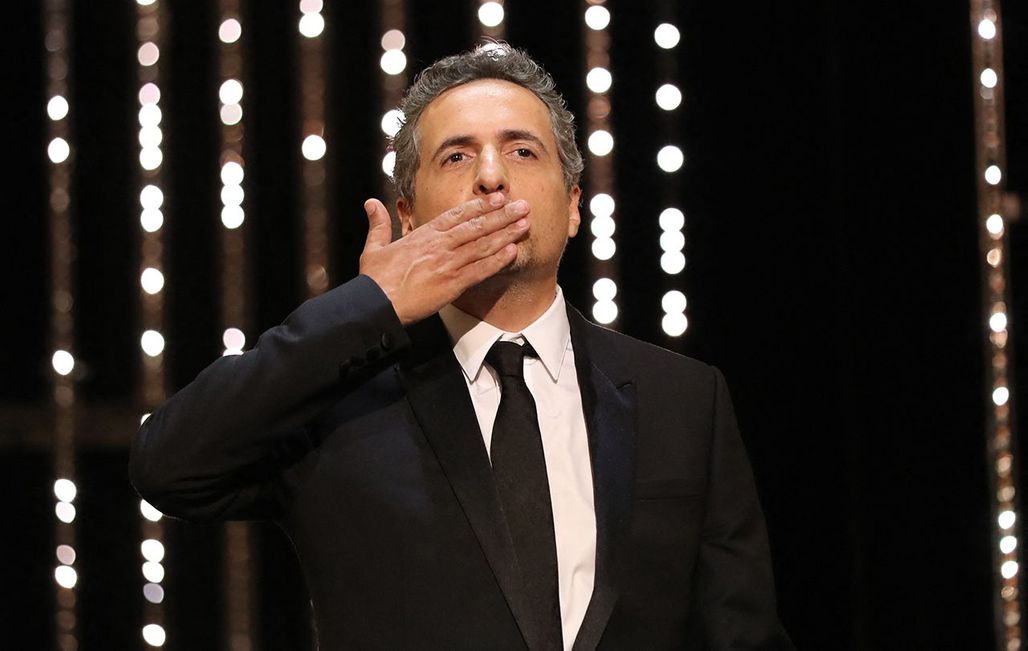

Interview with Kleber Mendonça Filho, member of the Feature Film Jury

Kleber Mendonça Filho embarked on a career as a critic and programmer before signing a highly acclaimed first feature film in 2012, Neighboring Sounds (O Som ao Redor). After Aquarius (2016), which marked his first appearance in Competition, Bacurau (2018), his latest film - which won the Jury Prize ex-aequo in 2019 - set itself up as an emblem of the resistance to Jair Bolsonaro. The filmmaker talks about his relationship with cinema and the situation in his native country.

We all have a film that once gave us the cinema bug. What was yours?

It's very difficult to choose just one because there are so many… but among them, I remember the impact of one film in particular on my love of films. It was released in 1990 in Brazil, but I discovered it on VHS because a long time passed before it was shown in the cinemas of Recife. The film was called Do The Right Thing, by a certain Spike Lee! He is one of the people who made me want to become a director and it is an honour for me to be on the jury with him.

What kind of film lover were you before you became a critic?

I've been hungry for films ever since I was a child. My mother very often took my brother and me to the cinema. I grew up in the 1970s and all the films that came out in the cinema at that time were incredible. Just imagine: I was eight years old when I saw Richard Donner's Superman (1978) on the big screen! I also clearly remember Steven Spielberg's Close Encounters of the Third Kind (1977) and John Landis' The Blues Brothers (1980). I was lucky enough to see all these great American films and I think it had an impact on my desire for cinema. It was an exclusively American film diet, but a powerful one! When I was 14 or 15, I suddenly realised that there were other kinds of films. And the first non-American film I saw that transported me was Fitzcarraldo (1982) by Werner Herzog. Then I started following other types of films!

You do not hesitate to anchor your criticism of Brazilian society in genre cinema. What is your relationship with this genre?

It came naturally to me because the films I watched as a child were very genre-oriented. An American Werewolf in London (1981) by John Landis, E.T. (1982) by Steven Spielberg, Halloween (1978) by John Carpenter or Piranha (1978) by Joe Dante… These were films like any others that it was normal to go to the cinema at the time. I also lived in England with my family when I was a teenager and that opened my eyes to other types of film. British television was full of great films. I discovered Australian cinema that was a bit crazy, Indian films and even the French cinema of Truffaut and Godard.

Can you describe your working method?

I take a lot of time to think about my scripts but I don't necessarily plan these periods of reflection. Many people think that writing a screenplay means spending time in front of a computer. But for me, it's mainly an act of reflection because ideas come to me all the time. And when I'm stuck, I think more, I watch films or hang out in my local bookstores to find inspiration. I'm also very connected to social networks, especially since life in Brazil has become absurd. They are a constant stream of humanity, both good and bad, and you often need to protect yourself from it. But it allows me to take the temperature of what's going on in the world. It's a bit like swallowing films at Cannes. After ten films, you manage to assess how the directors analyse the period they are going through. It's a powerful way of looking at things.

Bolsonaro's presence in power is not good news for culture. What can we fear for the cinema?

State funding for culture is enshrined in the Brazilian constitution. It's something that is set in stone, a bit like in France. There are great similarities between the two systems. Our far-right government does not understand it, does not tolerate it and does not like artists. They don't believe in supporting culture. They have not done anything officially to destroy this system because it works on a lot of bureaucracy. But they are sabotaging us by keeping the files in a corner of the table. We have about 8,000 film projects that are currently being blocked in this way, which means that technicians are not being paid and a whole industry is being affected. All Brazilians working in the cultural sector are in a very bad position at the moment because of this toxic relationship. And now, to top it all off, we have the epidemic.

How does the new generation of filmmakers perceive the situation?

A lot of film students tell me that they made the wrong choice to go into film. But it's the opposite! It's the best time to be a student, to love films and to want to make them. Tension is what makes the best human stories. I really think we are living in interesting times. When this government leaves office, the streams will reconnect.