AMERICAN CINEMA AT THE FESTIVAL DE CANNES

BY SCOTT FOUNDAS *

Given the historical love affair between America and France—the Enlightenment, the Statue of Liberty, Jerry Lewis—it comes as no surprise that American films have been a major presence on the Croisette ever since the beginning of the Festival de Cannes. Indeed, the festival’s first edition, in 1946, was something of an anus mirabilis for Hollywood, with eight American productions among the 44 features “in Competition,” including Cukor’s Gaslight, Hitchcock’s Notorious, Wilder’s Lost Weekend (one of nine films to share the Festival’s inaugural Grand Prix, then the top award) and Disney’s Make Mine Music, the start of a long tradition of animated features in the Official Selection. This was, perhaps not coincidentally, the same year that the historic Blum-Burnes agreement mandated the opening of French cinemas to more American product. Vive les États-Unis!

Given the historical love affair between America and France—the Enlightenment, the Statue of Liberty, Jerry Lewis—it comes as no surprise that American films have been a major presence on the Croisette ever since the beginning of the Festival de Cannes. Indeed, the festival’s first edition, in 1946, was something of an anus mirabilis for Hollywood, with eight American productions among the 44 features “in Competition,” including Cukor’s Gaslight, Hitchcock’s Notorious, Wilder’s Lost Weekend (one of nine films to share the Festival’s inaugural Grand Prix, then the top award) and Disney’s Make Mine Music, the start of a long tradition of animated features in the Official Selection. This was, perhaps not coincidentally, the same year that the historic Blum-Burnes agreement mandated the opening of French cinemas to more American product. Vive les États-Unis!

Hitchcock‘s Notorious

Of course, had Cannes begun as originally scheduled, in 1939—before World War II got in the way—it would have included The Wizard of Oz and DeMille’s Union Pacific among other treasures from that storied year in Hollywood history. (When a 1939 Palme d’Or was belatedly awarded in 2002, DeMille’s film was the winner.) Still, Cannes arrived in ample time to take advantage of Hollywood’s halcyon “Golden Age.”

|

|

| Edward Dmytryk’s The End of the Affair | Vincente Minnelli’s An American in Paris |

Throughout the end of the ‘40s and into the ‘50s, prestige studio pictures by the likes of Edward Dmytryk (Crossfire, The End of the Affair), Vincente Minnelli (Ziegfeld Follies, An American in Paris) and William Wyler (Detective Story, Friendly Persuasion) headed to the Cannes competition, as did a surprising number of genre pictures and “films noirs” like Fred

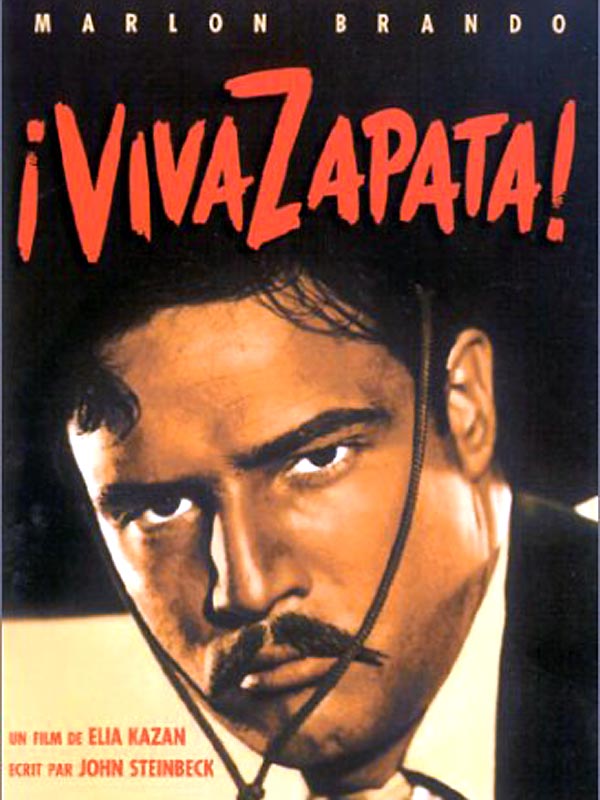

Throughout the end of the ‘40s and into the ‘50s, prestige studio pictures by the likes of Edward Dmytryk (Crossfire, The End of the Affair), Vincente Minnelli (Ziegfeld Follies, An American in Paris) and William Wyler (Detective Story, Friendly Persuasion) headed to the Cannes competition, as did a surprising number of genre pictures and “films noirs” like Fred  Zinnemann’s Act of Violence (1948) and Robert Wise’s The Set-Up (1949)—the sort of movies the French were, historically, the first to take seriously. In 1952, after three turbulent years of production, Orson Welles’ independently made Othello took home the Grand Prix—a year that also saw Marlon Brando (in Kazan’s Viva Zapata!) and Lee Grant (in Detective Story) take the festival’s top acting awards. In 1953, the great John Ford made his only appearance in Cannes with The Sun Shines Bright. Then, in 1955, the newly christened Palme d’Or was awarded in its first year to Delbert Mann’s Marty, the first of 14 American films to win that coveted trophy—more than any other country.

Zinnemann’s Act of Violence (1948) and Robert Wise’s The Set-Up (1949)—the sort of movies the French were, historically, the first to take seriously. In 1952, after three turbulent years of production, Orson Welles’ independently made Othello took home the Grand Prix—a year that also saw Marlon Brando (in Kazan’s Viva Zapata!) and Lee Grant (in Detective Story) take the festival’s top acting awards. In 1953, the great John Ford made his only appearance in Cannes with The Sun Shines Bright. Then, in 1955, the newly christened Palme d’Or was awarded in its first year to Delbert Mann’s Marty, the first of 14 American films to win that coveted trophy—more than any other country.

Orson Welles’ Othello

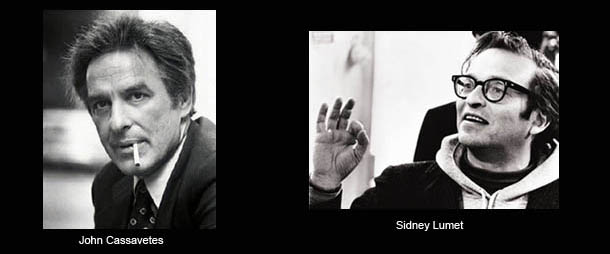

Just as the end of the 1950s witnessed seismic changes in the French film industry ushered in by the Young Turks of the Nouvelle Vague, American movies began to experience their own revolution, with independent directors like Morris Engel, John Cassavetes and Irvin Kershner (whose The Hoodlum Priest screened in competition in 1961) arriving on the scene, and other young filmmakers, like the television-trained John Frankenheimer and Sidney Lumet, chipping away at the conventional language of mainstream Hollywood cinema. Frankenheimer’s All Fall Down and Lumet’s Long Day’s Journey Into Night debuted in Cannes in 1962, with Lumet’s film taking a group Best Actor Palme for its trio of leading men (Dean Stockwell, Jason Robards and Ralph Richardson) and a Best Actress Palme for Katherine Hepburn. In 1965, the first year Cannes welcomed an American jury president in the person of Ms. Olivia de Havilland, the Palme d’Or went to Richard Lester’s groundbreaking Mod comedy The Knack…and How to Get It, and while the film itself was British to the core, it must be noted that Lester himself is an American. In 1967, only a single American film competed at the festival, and it was a low-budget independent that had begun as its director’s thesis project for the UCLA film school: the movie was called You’re a Big Boy Now, and the director a future two-time Palme d’Or winner named Francis Coppola.

Richard Lester’s The Knack…and How to Get It

The next year, the social turbulence of the ‘60s arrived full force on the Croisette, resulting in a famous case of festival interruptus. When (relative) order was restored in 1969, Dennis Hopper’s Easy Rider was there to announce that a new Hollywood cinema had arisen out of the ashes of Vietnam and the disillusioned American counterculture. Notably, the film screened in competition and not at the newly constituted, ostensibly more vanguard Directors’ Fortnight (which did manage to include another production of the influential BBS production company, Bob Rafelson’s Head, in its lineup).

Dennis Hopper’s Easy Rider

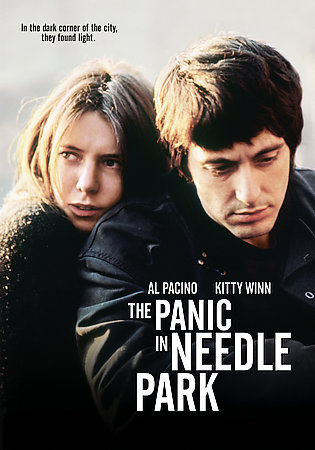

So the stage was set for a decade of brash, uncompromising, highly political auteur films from America, including Robert  Altman’s MASH, which won the 1970 Palme d’Or, though some of the jury was said to favor neophyte Stuart Hagmann’s campus revolution drama The Strawberry Statement (which had to settle for the Jury Prize). Blacklisted Dalton Trumbo unveiled Johnny Got His Gun in the same year (1971) that welcomed Jerry Schatzberg’s brilliant drug-addiction portrait Panic in Needle Park (featuring a pre-Godfather Al Pacino) and Milos Forman’s American debut, Taking Off, with its unforgettable scene of uptight bourgeois parents being taught how to smoke a joint. Schatzberg’s poetic, Palme d’Or-winning road movie Scarecrow, with Pacino and Gene Hackman in two of the best performances of their careers, won the 1974 Palme, and Martin Scorsese, whose Mean Streets had been a sensation at the Directors’ Fortnight in 1973, made his first competition appearance in 1975 with Alice Doesn’t Live Here Anymore.

Altman’s MASH, which won the 1970 Palme d’Or, though some of the jury was said to favor neophyte Stuart Hagmann’s campus revolution drama The Strawberry Statement (which had to settle for the Jury Prize). Blacklisted Dalton Trumbo unveiled Johnny Got His Gun in the same year (1971) that welcomed Jerry Schatzberg’s brilliant drug-addiction portrait Panic in Needle Park (featuring a pre-Godfather Al Pacino) and Milos Forman’s American debut, Taking Off, with its unforgettable scene of uptight bourgeois parents being taught how to smoke a joint. Schatzberg’s poetic, Palme d’Or-winning road movie Scarecrow, with Pacino and Gene Hackman in two of the best performances of their careers, won the 1974 Palme, and Martin Scorsese, whose Mean Streets had been a sensation at the Directors’ Fortnight in 1973, made his first competition appearance in 1975 with Alice Doesn’t Live Here Anymore.

Milos Forman’s Taking Off

Great names from Easy Rider and the future Raging Bull dominated the 1974 festival, with Coppola winning his first Palme for The Conversation—the ultimate in Watergate-era paranoia—while Jack Nicholson won Best Actor for his exuberant portrayal of a free-minded marine in Hal Ashby’s The Last Detail (written by the decade’s preeminent American screenwriter, Robert Towne), and a pair of first-time screenwriters, Hal Barwood and Matthew Robbins, were awarded for their first script Sugarland Express, which happened to also mark the feature directing debut of one Steven Spielberg. Two more American Palme winners, Taxi Driver (1976, from a jury headed by Tennessee Williams!) and Apocalypse Now, would round out the decade, just as Hollywood itself began to tilt towards a more conservative, blockbuster-friendly model.

Great names from Easy Rider and the future Raging Bull dominated the 1974 festival, with Coppola winning his first Palme for The Conversation—the ultimate in Watergate-era paranoia—while Jack Nicholson won Best Actor for his exuberant portrayal of a free-minded marine in Hal Ashby’s The Last Detail (written by the decade’s preeminent American screenwriter, Robert Towne), and a pair of first-time screenwriters, Hal Barwood and Matthew Robbins, were awarded for their first script Sugarland Express, which happened to also mark the feature directing debut of one Steven Spielberg. Two more American Palme winners, Taxi Driver (1976, from a jury headed by Tennessee Williams!) and Apocalypse Now, would round out the decade, just as Hollywood itself began to tilt towards a more conservative, blockbuster-friendly model.

Martin Scorsese’s Taxi Driver

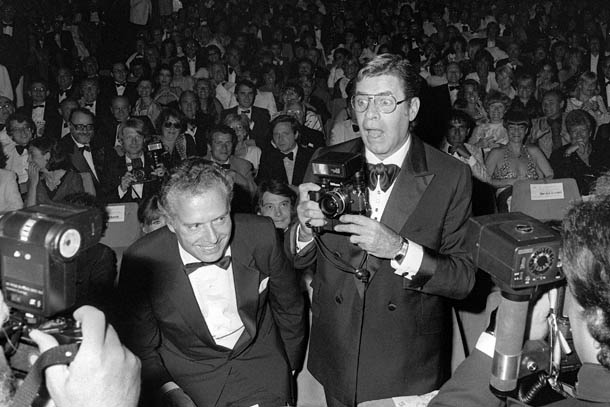

If the high-profile failure of Michael Cimino’s very brilliant, criminally underrated Heaven’s Gate (1981) signaled the official end of the New Hollywood, the 1980s nevertheless brought to Cannes the likes of Sam Fuller’s The Big Red One (shown in 1980 in a truncated, studio-imposed edit, and again in 2004 in a gloriously restored director’s cut), Michael Mann’s Thief (1981) and Scorsese’s King of Comedy (1983), which brought co-star Jerry Lewis to the red carpet of the Palais. And over at the newly launched Un Certain Regard parallel section, one could discover the work of the indefatigable American independent Henry Jaglom (Sitting Ducks, Someone to Love).

Jerry Lewis, Cannes, 1982.

Michael Cimino’s Heaven’s Gate

The Cannes selection was now firmly in the hands of Gilles Jacob, who had been hired to replace outgoing festival director Maurice Bessy in 1976, only to find his predecessor not quite willing to relinquish power…for the next two years! By the end of the ‘80s, however, Jacob had built important and long-lasting relationships with Clint Eastwood, Woody Allen and the Coen Brothers, all of whom continue to premiere their films at Cannes to this day. It is an achievement all the more remarkable in that this decade was hardly one of Hollywood’s most golden, as the studios once run by Irving Thalbergs and Harry Cohns fell under the sway of corporate conglomerates focused narrowly on the bottom line. So another “new” Hollywood came to emerge, with its high-concept, big-budget blockbusters, easily marketable and merchandisable all over the globe—without needing to be adapted in any way.

Woody Allen’s The Purple Rose of Cairo (1985)

Steven Spielberg‘s E.T. The Extra Terrestrial

In fact, this wasn’t entirely a bad thing, as it gave wunderkinds like Spielberg an opportunity to flourish with work like E.T. The Extra Terrestrial (which had its world premiere at the festival’s closing night in 1982). Yet, for most of the decade, the American cinema on display in Cannes was of a smaller, more personal variety—much of it made by foreign émigré directors working outside the studio system, or in the case of Paul Schrader’s Mishima: A Life in Four Chapters (1985), an American director working very far away from the comforts of home. Germany’s Wim Wenders explored the landscape of Paris, Texas, winning the 1984 Palme in the process, while Italy’s Sergio Leone screened his masterful Jewish-American gangster epic Once Upon a Time in America Out of Competition. France’s Barbet Schroeder took on the life of Los Angeles’ alcoholic poet laureate, Charles Bukowski, in Barfly (1987), and Russia’s Andrei Konchalovsky—a Grand Jury Prize winner for his 1979 Siberiade— ventured deep into the Louisiana bayou to make Shy People (for which Barbara Hershey won the Best Actress award). These last two films were also the work of two maverick Israeli producers, Menahem Golan and Yoram Globus, who had taken over a failing American distribution company called Cannon and turned it into a prolific maker of both low-budget exploitation movies and surprisingly high-minded auteur cinema—at least until some unethical business practices got the better of them.

ventured deep into the Louisiana bayou to make Shy People (for which Barbara Hershey won the Best Actress award). These last two films were also the work of two maverick Israeli producers, Menahem Golan and Yoram Globus, who had taken over a failing American distribution company called Cannon and turned it into a prolific maker of both low-budget exploitation movies and surprisingly high-minded auteur cinema—at least until some unethical business practices got the better of them.

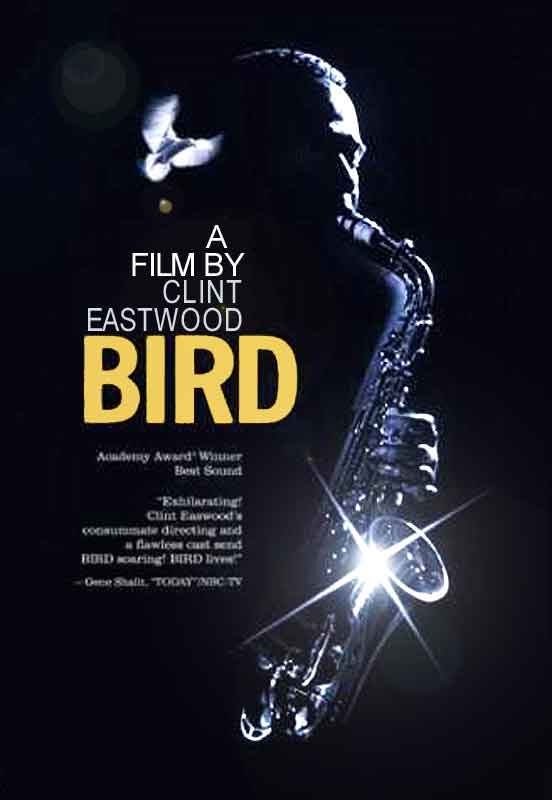

Around the same time, an upstart American film festival, first called the Utah/US Film Festival and later Sundance, was gathering steam as a showcase for new work from a renewed American independent cinema. Cannes was quick to take note. Of the 1988 competition selections, only Clint Eastwood’s Bird bore the logo of a major studio, while Schrader’s Patty Hearst and actor Gary Sinise’s debut feature Miles From Home hailed from the upstart indie sector. The following year, the Sundance and Cannes universes collided when Steven Soderbergh’s Sex, Lies and Videotape went from an Audience Award at the Utah festival to a Palme d’Or (and a Best Actor prize for James Spader) on the Croisette, besting Spike Lee’s Do the Right Thing.

The American indie domination of Cannes continued over the next two years, with David Lynch’s Wild at Heart and the Coen Brothers’ Barton Fink winning the two subsequent Palmes—in an unprecedented trifecta, Joel Coen was named Best Director for Barton too, with a third prize for best actor going to star John Turturro. By 1992, Cannes seemed in the throes of a veritable Yank invasion, with six U.S. films (including Altman’s The Player and Lynch’s notorious Twin Peaks: Fire Walk with Me) selected for Competition, alongside another four (including Abel Ferrara’s Bad Lieutenant) in Un Certain Regard and three more (including Quentin Tarantino’s Reservoir Dogs) screened Out of Competition. But as the ‘90s moved on, this hot streak seemed to be cooling: For every unqualified American sensation at Cannes in these years (Pulp Fiction, Ed Wood, L.A. Confidential), there was a much longer trail of second-rate work by great filmmakers (John Boorman’s Beyond Rangoon, the Coens’ Hudsucker Proxy, Altman’s Kansas City, James Ivory’s Jefferson in Paris), good films relegated to obscurity by uncomprehending studios (Ferrara’s Body Snatchers, Soderbergh’s King of the Hill, Cimino’s Sunchaser) and the cosmic folly of Johnny Depp’s directorial debut, The Brave, deservedly cast into obscurity by its own maker.

|

|

| Quentin Tarantino’s Pulp Fiction |

Curtis Hanson’s L.A. Confidential |

Robert Altman’s The Player

Somehow, it seemed, America and Cannes had drifted apart, and it would be up to the new sheriff in town to bring them back together again. “When I came to Cannes, one of the first things Gilles asked me was to go to Hollywood and to make a new connection with American cinema and especially with the studios,” Thierry Frémaux, who succeeded Jacob as Cannes’ Artistic Director in 2001, told this writer in a 2007 interview. And it was a demand Frémaux took to heart, making multiple annual trips to Los Angeles and re-establishing a strong link between Cannes and today’s A-list directors, studio heads and other reigning power brokers.

The dividends were immediate, with 20th Century Fox offering Baz Luhrmann’s Moulin Rouge for the opening night of the 2001 Festival—a markedly strong year that also featured the premieres of David Lynch’s Mulholland Dr. and the Coens’ The Man Who Wasn’t There (which shared the Best Director Award), and of Shrek, officially signaling the arrival of computer animation on the Croisette. The following year brought with it the first competition documentary in decades, Michael Moore’s Bowling for Columbine, as well as the first competition appearances of Alexander Payne (About Schmidt) and Paul Thomas Anderson (Punch-Drunk Love), two of the increasingly rare American directors managing to make auteur films with studio-sized budgets. And the Cannes of the millennial decade continued apace, showcasing a broad range of American movies from the populist heights of the Matrix and Star Wars franchises (in the ever-more numerous slots devoted to Out of Competition films) to what some deemed the naval-gazing lows of Vincent Gallo’s The Brown Bunny (2003)—a film still defended by its creator.

The dividends were immediate, with 20th Century Fox offering Baz Luhrmann’s Moulin Rouge for the opening night of the 2001 Festival—a markedly strong year that also featured the premieres of David Lynch’s Mulholland Dr. and the Coens’ The Man Who Wasn’t There (which shared the Best Director Award), and of Shrek, officially signaling the arrival of computer animation on the Croisette. The following year brought with it the first competition documentary in decades, Michael Moore’s Bowling for Columbine, as well as the first competition appearances of Alexander Payne (About Schmidt) and Paul Thomas Anderson (Punch-Drunk Love), two of the increasingly rare American directors managing to make auteur films with studio-sized budgets. And the Cannes of the millennial decade continued apace, showcasing a broad range of American movies from the populist heights of the Matrix and Star Wars franchises (in the ever-more numerous slots devoted to Out of Competition films) to what some deemed the naval-gazing lows of Vincent Gallo’s The Brown Bunny (2003)—a film still defended by its creator.

The Coen brothers’ Fargo (1996)

Increasingly, the Palais des Festivals’ red carpet seemed to extend all the way from the Croisette to the Academy Awards, in the case of the majority of the films already mentioned, and also Mystic River, Fahrenheit 9/11, A History of Violence, An Inconvenient Truth, No Country for Old Men, Changeling, Precious and Blue Valentine. At the same time, films like Alejandro Gonzalez Iñarritu’s Babel and Tarantino’s Inglourious Basterds, both technically American productions, continued to blur the lines of nationality and language in our increasingly globalized society. What country, after all, can truly lay claim to Lars von Trier’s magnificent Dogville, a movie funded with Euros, but filmed in English and set in an imaginary America drawn from the dream factory of classic Hollywood? Or the films made by Woody Allen during his extended European vacation? And so we venture forth into the 2010s, and Terrence Malick looms on the horizon.

* Scott Foundas is a film critic and programmer. He is Associate Program Director for the Film Society of Lincoln Center and a regular contributor to Film Comment and other publications.

The Festival de Cannes would like to thank the authors for contributing for free.