Birth of a Festival

2017 marks the Festival's 70th year, but when was the world's greatest film festival actually born? 1939? 1946? With the abortive first season, not to mention the two festivals cancelled due to lack of funding and a third because of political upheaval (1968), pinning down the exact age of the Festival de Cannes is no easy matter. A look back at the birth of the event might shed some light on the affair...

Fighting fascism: the political origins of the Festival

The desire to create an international film-based event in France owes its inspiration to another Festival. In 1932. the Venice Biennial – a major international artistic gathering – had decided to dedicate part of its programme to film. Alongside the Academy Awards (Oscars), the Mostra was one of the biggest international events to celebrate the silver screen.

In 1938 however, the Festival became one of the mainstages on which Italian politics under Mussolini, and his relations with Nazi Germany were played out. After Renoir's pacifist film Grand Illusion had been honoured the previous year, Goebbels was adamant that German films should feature among the prizewinners. At the last moment, and despitethe fact that the rules prohibited the awarding of prizes to documentaries, Leni Riefenstahl's Olympia won the Mussolini Cup, in joint first position with the Italian director Goffredo Alessandrini's Luciano Serra, Pilot, supported by the Duce's son Vittorio Mussolini, who controlled the film industry in Italy. The delegations sent by democratic nations were furious: Great Britain and the United States stormed out of Venice, vowing never to return. The lack of a neutral and free venue in which to showcase its work rapidly aroused the indignation of the film industry. The need for an alternative to the Venetian festival became apparent, not only in political but also in artistic circles.

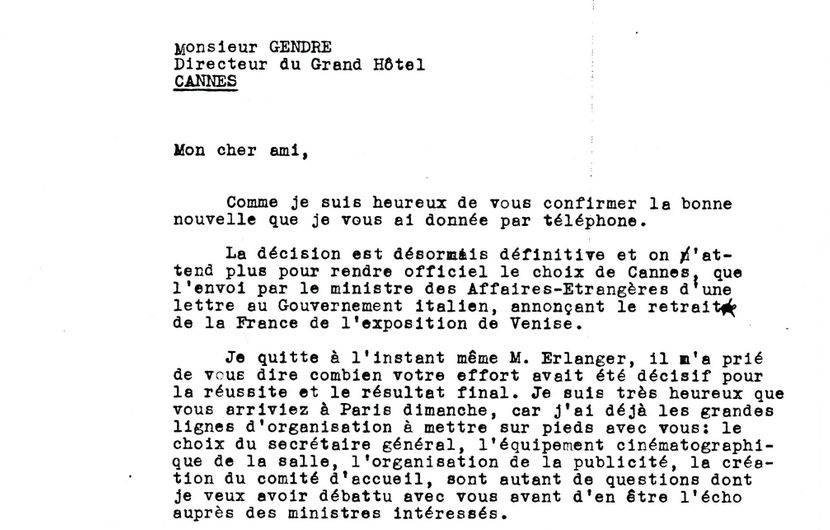

Philippe Erlanger, the brains behind the Festival

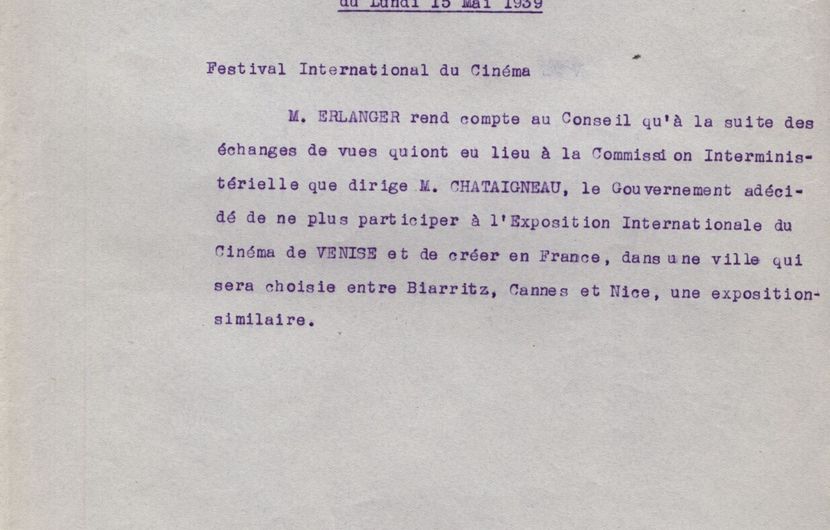

On 3 September 1938, on the return train journey from Venice to Paris, Philippe Erlanger, the French government representative at the Venice Festival and the Inspector General at the Ministry of Education and Fine Arts in charge of film, came up with the idea to turn France into a new forum for international cinema. In his report to Education and Fine Arts Minister Jean Zay, he listed the many political and economic benefits that organising an international festival would bring the country that was the birthplace of cinema.

The government was initially wary: in the international context at the time, just after the Munich peace agreement, the danger of insulting Italy on the diplomatic front made officials uneasy. Besides, public opinion was largely content with the prize awarded 'To the entire French production' at the 1938 Mostra.

Some months would go by before Jean Zay and Interior Minister Albert Sarraut finally gave their consent for the event to go ahead. The Association Française d’Action Artistique, under Zay's Ministry and connected for diplomatic matters to the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, was entrusted wwith establishing the foundations of the Festival under the leadership of Philippe Erlanger.

Extending France's influence and developing its film industry

The desire to create a democratic counterpoint to the Mostra was based not only on political but also on artistic grounds: the aim was to extend France's influence as well as contributing to the economic development of its film industry. In fact, Jean Zay wanted the State to help structure the entire profession, using this new world stage to promote the French film industry.

The Americans also played a part in Philippe Erlanger's plans. When Harold Smith, representing the American film industry, walked out of the Mostra, it was primarily an act of political protest against the totalitarian direction the event had taken. However, when the fascist Italian government passed a protectionist law guaranteeing itself a monopoly of the import and distribution of foreign films, on 13 September 1938, the American withdrawal also turned into an economic protest. The US film industry, seeking a new entry point to infiltrate the European market, fully supported the plans for an international film event in France. The opening of the French market to their productions, ratified in the 1946 Blum-Byrnes accords, was certainly an advantage for the Americans. Meanwhile, France seized the chance to have Hollywood participate in the plans, thus giving its own films access to the American market.

1939, the birth of a Festival

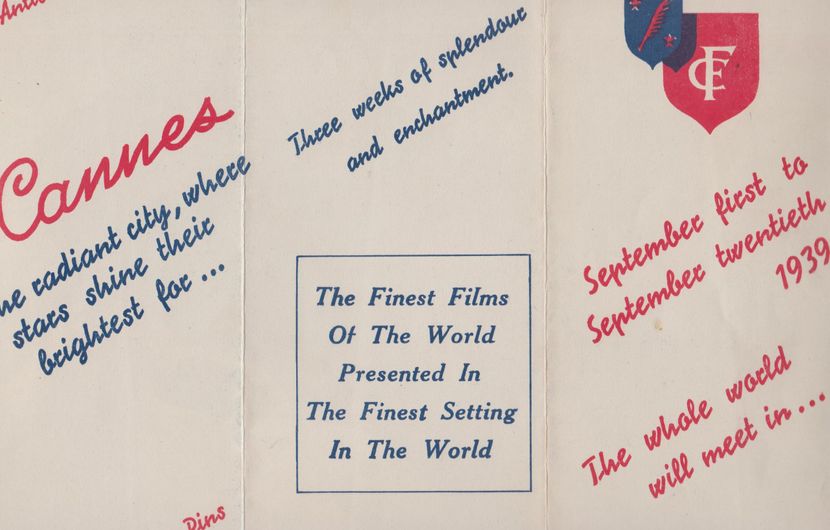

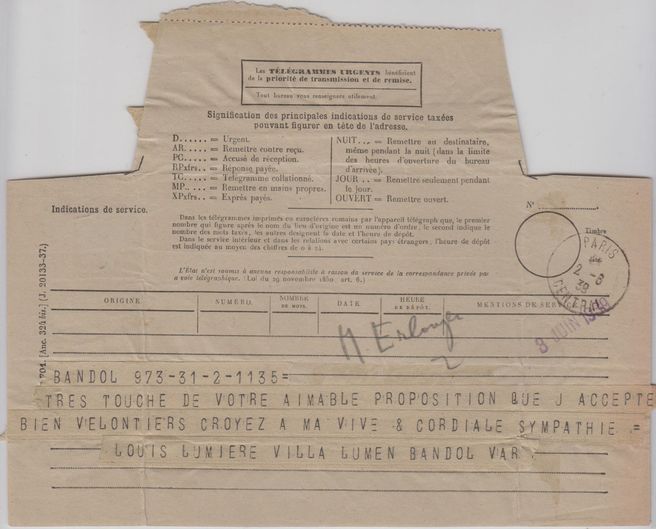

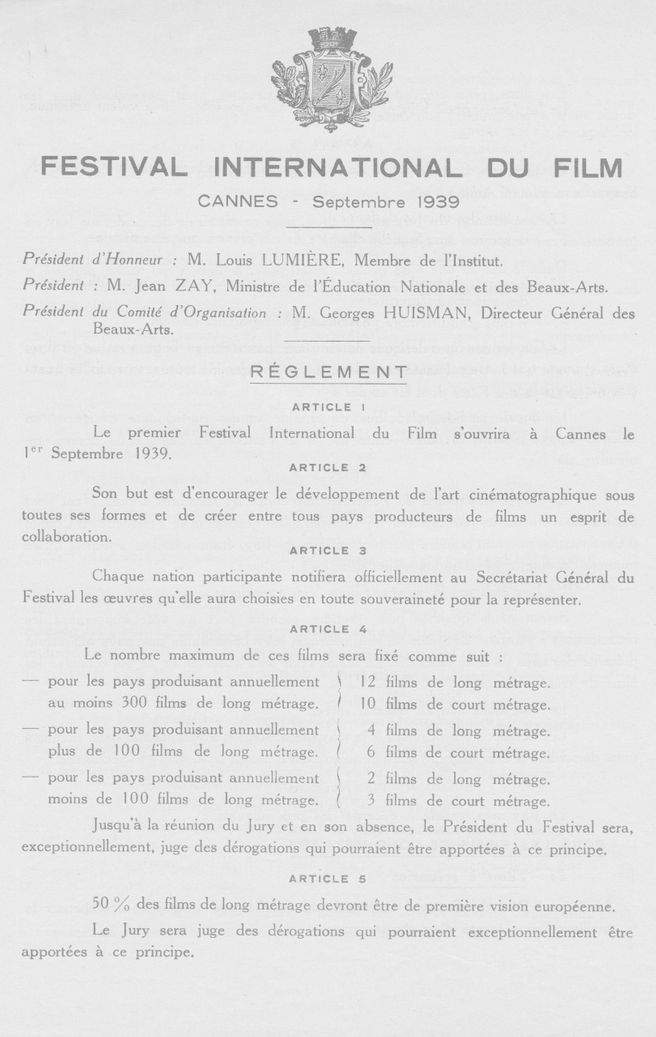

For the first ever event, scheduled for 1 September 1939, it was decided that the Festival would open under the presidency of Louis Lumière, the inventor of Cinematography. The invitations were sent out. Germany and Italy were invited, but to no-one's surprise, refused to attend. The United States, Great Britain and the Soviet Union all promised to be there.

As one of the main objectives was to preserve good diplomatic relations, each guest country chose the films it wanted to present and designated a member of the Jury. And in order to prevent undue rivalry, it was decided that each country would receive a 'Grand Prix'.

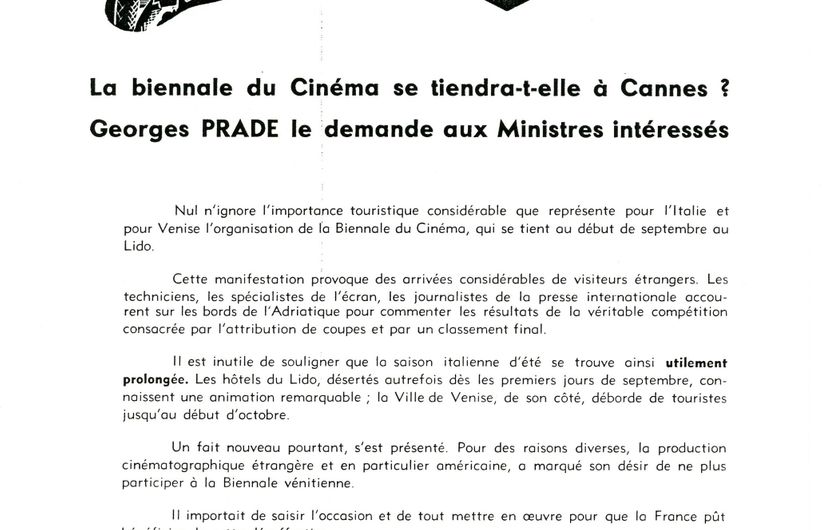

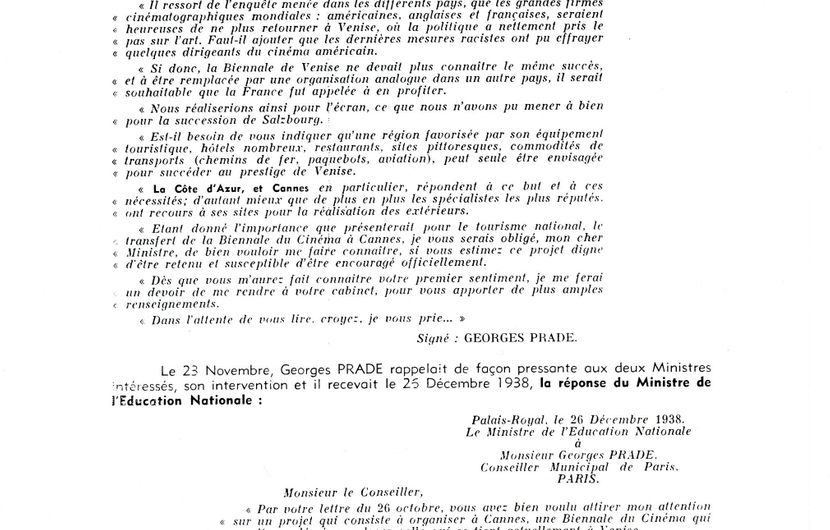

The choice of Cannes as a venue

The next task was to determine the place where the festivities would take place. In a bid to match the charm of Venice, all eyes turned to the South of France, with its sea, sun and extensive range of hotels. The economic benefits of such an event were significant, and several towns lined up to be candidates. Biarritz and Cannes were the final contenders, but thanks to the lobbying talents of Henry Gendre, manager of the Grand Hotel and Georges Prade, a municipal and departmental councilor working in Paris, the ultimate choice fell on the pearl of the Riviera, particularly given its ability to rapidly set up a cinema. The town's hoteliers soon understood that this was an ideal way to boost the tourist season and offered their full support in seeing the project through to fruition.

Challenging destiny

Georges Huisman, then director of the Beaux-Arts, was appointed by the Association Française d’Action Artistique to the head of the Organising Committee. With barely ten weeks in which to set up an event of international stature and organise the festivities, Philippe Erlanger said: 'We are truly challenging destiny.' But the members of the committee were far from inexperienced in these matters. Jean Zay's administration had already organised the Universal Expo in Paris in 1937 and the Association Française d’Action Culturelle had overseen the centenary of the French Revolution that same year, earlier in 1939.

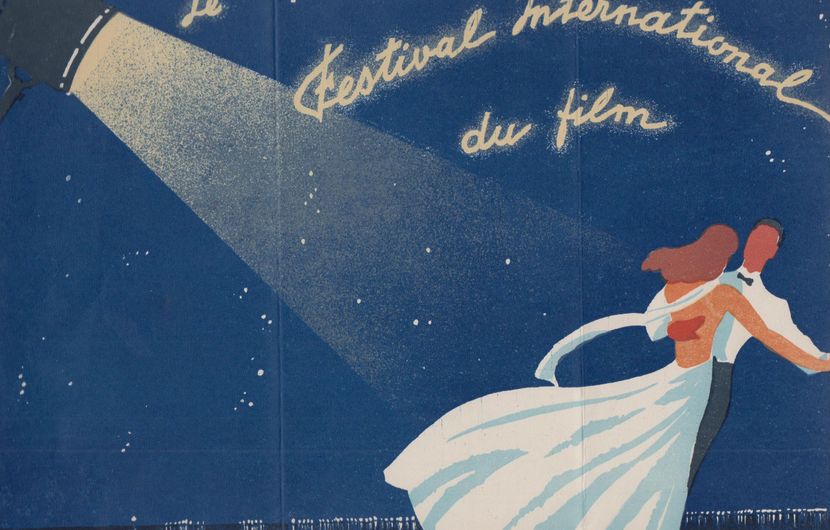

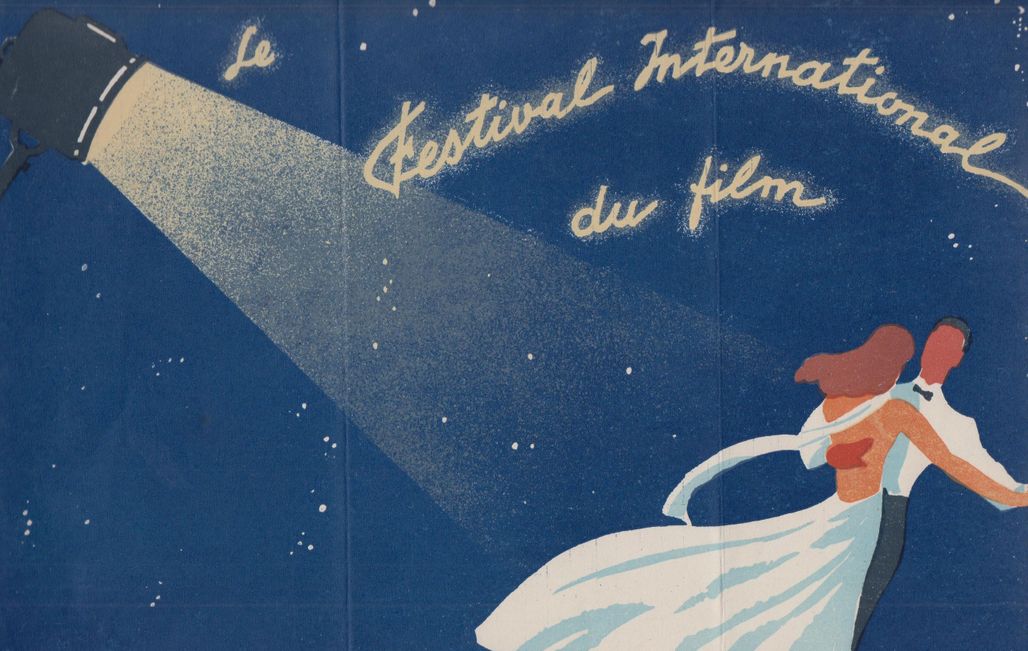

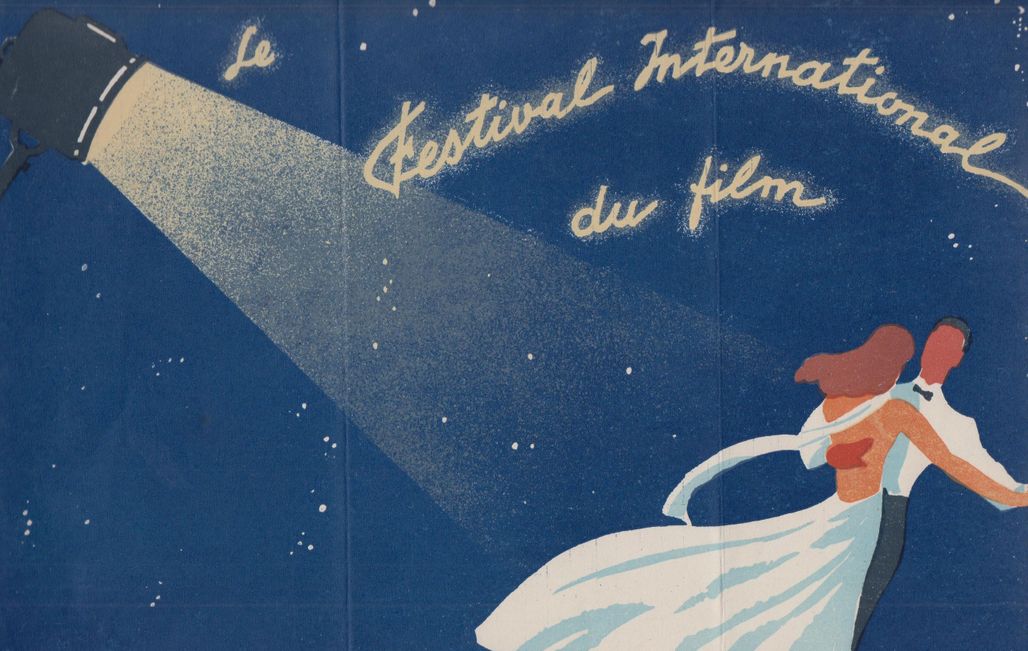

In Cannes, the Casino Municipal was converted into a cinema hall. A large room was set up in the main hall while the adjacent theatre was turned into a cinema to host the screenings reserved for the press and the Jury. The promotion of the event and the invitations to the stars were all part of the preparatory work leading up to the launch. Meanwhile, the design of the poster was entrusted to local painter Jean-Gabriel Domergue, and represented the first ever spectator couple at the Festival de Cannes.