CHINESE CINEMA AND THE FESTIVAL DE CANNES

BY CHARLES TESSON *

|

The first season of the Festival de Cannes took place in 1946, in the aftermath of the Second World War. Following victory over Japan, with which it had been at war since 1937, China was now in the throes of civil war between the Kuomintang’s Nationalist troops led by CHIANG Kai-Shek and the Communist forces, which took power in 1949, leading to the creation of the People’s Republic of China. As much as Taiwan rejoiced in the pull-out of the Japanese, the arrival of the Nationalists, followed by their exile after the defeat in 1949 cast a shadow over their destiny. The provisional government of the Republic of China, born on the continent in 1911, set up its headquarters in Taiwan and decreed martial law, which was lifted in 1986. The British colony of Hong Kong, on the other hand, was later to be victim of the Japanese occupation, before regaining its former status, which it held until 1997.

|

|

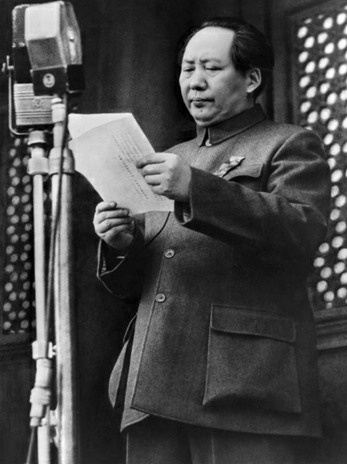

| Zhang Sichuan | Offices of the Mingxing Films Company |

Cinema arrived very early in China, with films by the Lumière brothers screened in Shanghai as early as 1896, followed by films made by Edison the following year, but it was not until 1913 that the first feature film, entitled The Difficult Couple, was shot by ZHANG Sichuan. 1922 saw the creation of Mingxing, the largest film production company of the period, along with Tianyi (founded by the Shaw brothers, and later operating in Hong Kong). After the wave of realistic dramas, sword-fighting films came into fashion as the dominant genre in the 1920s. From 1930, with the founding of Lianhua (the “United China Film Company”), the occupation of Manchuria in 1931 and the bombing of Shanghai in 1932, entertainment films were set aside in favour of a progressive cinema that was engaged with reality.

|

| Hu Die |

|

| Ruan Lingyu |

This first golden age (1931-1937) saw the emergence of female stars (HU Die, RUAN Lingyu) and a second generation of talented film makers: SUN Yu, CHENG Bugao, CAI Chusheng, YUAN Muzhi, WU Yonggang. The war against the Japanese (1937-1945) ruptured this dynamic, with some film makers remaining in Shanghai, some finding refuge in Hong Kong and others joining the Long March. Although it was a troubled time, the period of civil war (1945-1949) gave birth to beautiful films such as Spring in a Small Town (FEI Mu, 1948) and Crows and Sparrows (ZHENG Junli, 1949).

The 3rd generation of film makers began with the birth of the People’s Republic (SHUI Hua, LING Zifeng, SANG Hu, XIE Jin, XIE Tieli), making Beijing the new centre for cinema. While Japanese and Indian films were being celebrated in Cannes at that time, Communist China was not represented at all. The 1960s were the years of the sacrificed generation (the 4th), because their careers were interrupted by the Cultural Revolution. When Chinese cinema resumed normal activity in the second half of the 1970s, Cannes was forging new ties with China. This began with the screening in 1979 (Un Certain Regard) of Threshold of Spring by SHIE Tieli, which had been made in 1963, before the Cultural Revolution, the later The True Story of Ah Q (1982) by CEN Fan, a former actor and director of opera films in the 1950s, The Herdsman or Mu Ma Ren (UCR, 1983) by the Shanghai director XIE Jin, author of Stage Sisters (1965), as well as A Girl from Hunan or Xiangnu Xiaoxiao (UCR, 1987) by XIE Fei, a 4th generation director.

|

|

| Spring in a Small Town, FEI Mu | Crows and Sparrows, ZHENG Junli |

|

|

| The True Story of Ah Q, CEN Fan | A Girl from Hunan or Xiangnu Xiaoxiao, XIE Fei |

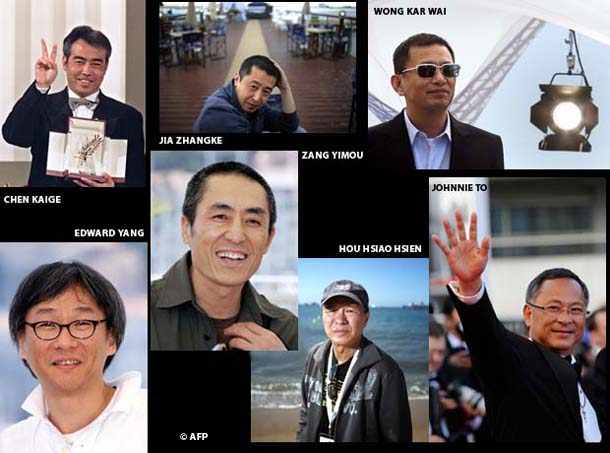

The early 1980s ushered in the 5th generation of Chinese cinema, with Yellow Earth by CHEN Kaige (1984) and Red Sorghum by ZHANG Yimou (winner in 1987 of the Golden Bear in Berlin). ZHANG Yimou was invited to Cannes with Ju Dou (1990), commencing a long relationship that would be renewed with To Live (1994), and with three more films prior to House of Flying Daggers (HC, 2004). CHEN Kaige was in Cannes with his fourth film, Life on a String (1991), and then with Farewell My Concubine (1993), which received the Palme d’Or.

The events in Tiananmen Square in 1989 gave a new generation of film makers (the 6th) an acute awareness of the limits of any opening up to democracy. This generation was represented in Cannes by ZHANG Yuan (East Palace, West Palace, UCR, 1997), and then by the WANG Xiaoshuai’s third film, So Close to Paradise (UCR, 1999); three other films of his have been selected (Drifters, Shanghai Dreams, Chongqing Blues). JIA Zhangke (Xiao Wu, Artisan Pickpocket, 1988, Platform, 2000), was invited to Cannes with Unknown Pleasures (2002), and later with 24 City (2008) and his documentary on the history of Shanghai (I Wish I knew, UCR, 2010). If Chinese cinema has become a standard fare in Cannes (LOU Ye, with this third film Purple Butterfly in 2003, and then with Summer Palace in 2006 and Spring Fever, in 2010), the festival has also screened films that are unique and unforgettable, like Devils on the Doorstep (2000) by the actor-director JIANG Wen, a film that brought him reprisals in his own country, and Petition (Special Screening, 2000), ZHAO Liang’s fascinating documentary, a very rich genre (see also WANG Bing), and the most adept genre for expressing the current Chinese reality today.

HONG KONG

In the early 1930s, the production companies in Shanghai, motivated by the success of the first “talkie” in Cantonese (White Golden Dragon, TANG Xiaodan, 1932), opened subsidiaries in Hong Kong (Daguan, Nayang) to produce films in the local language. After 1937, a number of film makers from Shanghai came to work there, fleeing the Sino-Japanese war, before being caught up in it once again. From 1945, the local film industry was developing with productions in Cantonese (Kung-fu, Cantonese opera, musical films, melodramas) and in Mandarin, thanks to Shanghai film makers like LI Pinqian and ZHU Shilin, the latter an auteur of memorable dramas of social realism. This cinema, which was not widely exported, remains quite unknown today.

In the early 1930s, the production companies in Shanghai, motivated by the success of the first “talkie” in Cantonese (White Golden Dragon, TANG Xiaodan, 1932), opened subsidiaries in Hong Kong (Daguan, Nayang) to produce films in the local language. After 1937, a number of film makers from Shanghai came to work there, fleeing the Sino-Japanese war, before being caught up in it once again. From 1945, the local film industry was developing with productions in Cantonese (Kung-fu, Cantonese opera, musical films, melodramas) and in Mandarin, thanks to Shanghai film makers like LI Pinqian and ZHU Shilin, the latter an auteur of memorable dramas of social realism. This cinema, which was not widely exported, remains quite unknown today.

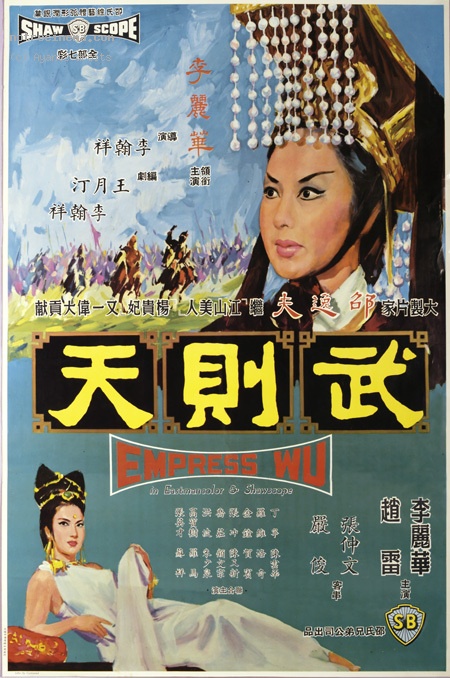

The arrival of the big studios like Cathay and Shaw (with the Shao brothers from the Tianyi production company) inspired new ambitions in the industry, with sword-fighting films, imperial Court dramas, and filmed Chinese operas. Cannes was tuned into the work of the unjustly forgotten first star director from the Shaw studios, LI Han-Hsiang, screening his films The Enchanting Shadow, (Qingnü youhun, 1960), a historic drama (The Magnificent Concubine, Yang Kwei Fei, 1962) and Empress Wu Tse Tien (1963). The Shaw studios produced sword-fighting films in Mandarin (in the 1960s, and then subsequently kung-fu films inspired by Shaolin) and the rival studio, Golden Harvest, launched the revival of serious kung-fu films in Cantonese with Bruce Lee and accompanied by kung-fu comedy with Jackie Chan.

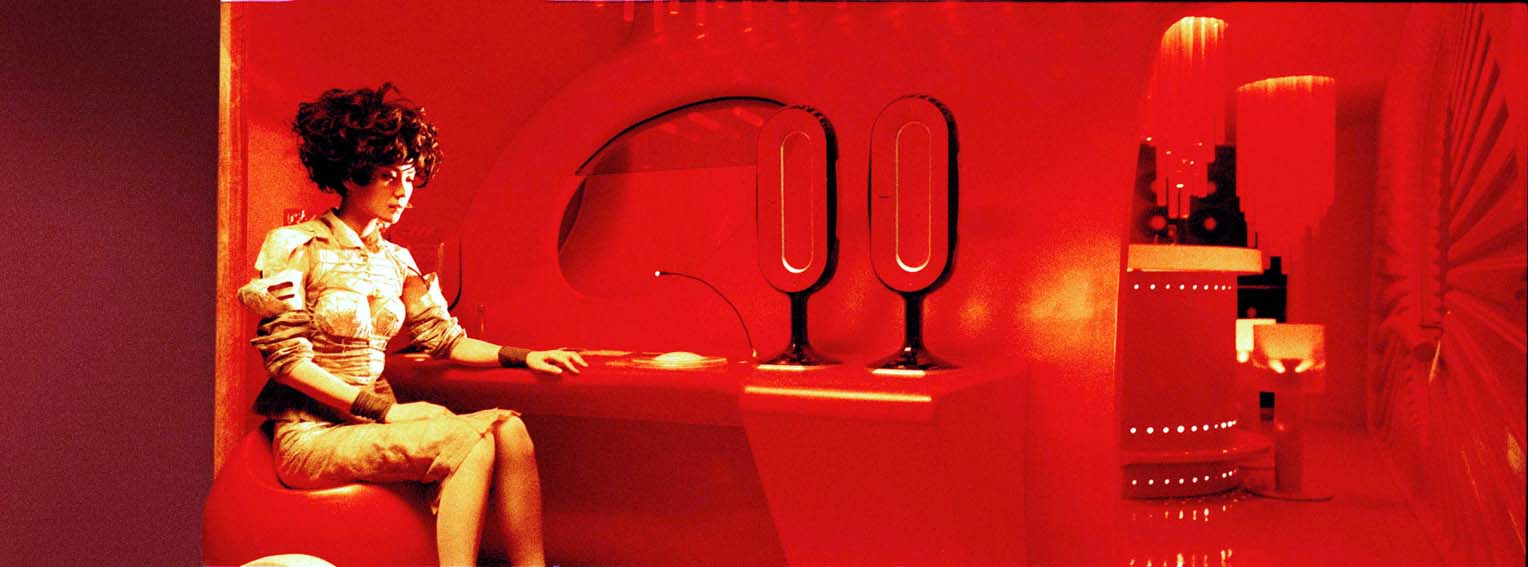

If, within the new generation of the 1980s, the Festival de Cannes overlooked TSUI Hark, belatedly present with Triangle (HC in 2007, co-directed by Ringo LAM and Johnnie TO), it made a hit with the screening of the fourth film of Ann HUI, Boat People (HC, 1983) followed by Song of Exile (UCR, 1990). On the other hand, for Cannes, WONG Kar-Wai is the film maker of Hong Kong, ever since Happy Together (1997, his fifth film), winner of the award for Best Director, and then In the Mood for Love (2000) and 2046 (2006).

.

The cinema of Johnnie TO benefitted from the renewed interest in the Hong Kong detective film genre, made famous by the films of John WOO. Although Johnnie TO’s recent work has been more commercial, he has taken a more stylised turn and received acclaim in Cannes with Breaking news (HC 2004), Election (2005), Election 2 (HC, 2006) and Vengeance (2009). This recognition is not surprising, as he has come to represent, on the international scene, (along with several others, including WONG Kar-Wai, TSUI Hark, and John WOO, who is now back in China) the cinema of Hong Kong.

TAIWAN

|

| The Sandwich Man, 1983 |

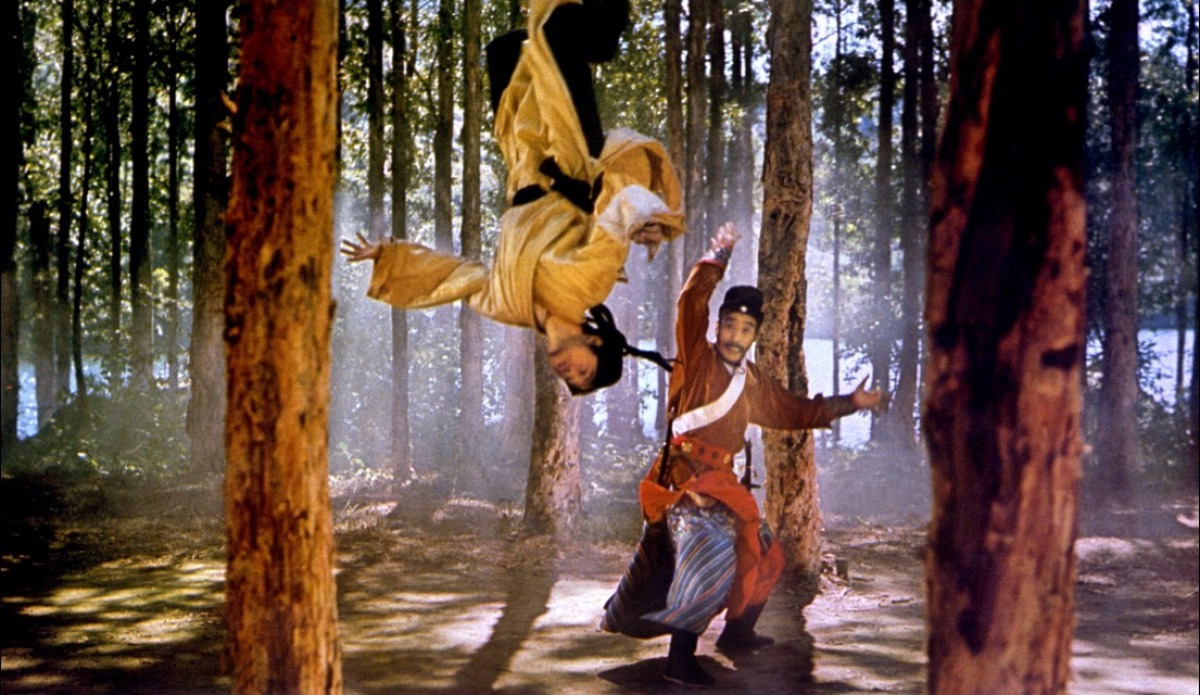

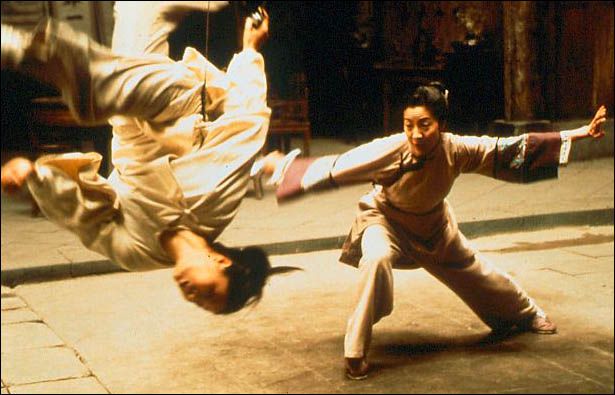

From a factual point of view, it is incorrect to say that Taiwanese cinema was born with the new cinema (the two decisive omnibus films of which are In Our Time, 1982 and The Sandwich Man in 1983), even if, in light of its history, the statement may be understandable. After the Japanese occupation, Taiwan was subjected to the occupation of the Kuomintang Nationalists, who imposed the production of propaganda films in Mandarin. When LI Han-Hsiang and King HU, his former assistant and now director, left the Shaw studios to withdraw to the island, the quality of film production was greatly enhanced. These historical productions, focusing on Imperial China, were divorced from the present-day reality (an orientation to which the government did not object). This was the breach in which the New Cinema was to settle itself, in its preoccupation with the unique history of Taiwan over the previous century. After having shown its support for LI Han-Hsiang when he was working in Hong Kong, Cannes presented King HU’s masterpiece, Touch of Zen (1975), a sword-fighting film, a genre that was unknown at that time outside China. This seminal work, would be imitated often (ZHANG Yimou) but never equalled. Indeed, Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon (Ang LEE, HC, 2000) was not the first sword-fighting film to be screened at Cannes.

|

| Touch of Zen, King HU, 1975 | Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon, Ang LEE, 2000 |

While the New Cinema was present at several festivals (in Europe: Pesaro, les Trois Continents) that screened the films of HOU Hsiao-hsien (The Boys from Fengkuei, 1983, A Summer at Grandpa’s, 1984, A Time to Live, a Time to Die, 1985, Dust in the Wind, 1986) and those of Edward Yang, albeit in a less prolific manner (Taipei Story, 1985), the Festival de Cannes invited HOU Hsiao-hsien to screen The Puppetmaster (1993), the director having been honoured with a Lion d’or in Venice for A City of Sadness (1989). This was the start of a wonderful and loyal relationship with Cannes that was to be extended with Good Men, Good Women (1995), Goodbye South, Goodbye (1996), Flowers of Shanghai (1998), Millennium Mambo (2001), Three Times (2005) and The Flight of the Red Balloon (CR, 2007). For his part, TSAI Ming-Liang, noticed for his films Rebels of the Neon God (1992), Vive l’amour (1994) and The River (1997) entered the Competition in Cannes with The Hole (1995) and then with What Time is it there? (2001) and Face (2009). It was thanks to the Festival de Cannes that Edward Yang obtained international acclaim for Yi Yi (2000), winning the Best Director’s award, although the Festival de Cannes had already screened A Confucian Confusion in 1994. He died of cancer at the age of 59 in 2007, and one can only regret that That day, on the Beach (1983) and even more so his masterpiece, A Brighter Summer Day (1991), a film of four hours duration, did not receive such attention in their time.

|

| Flowers of Shanghai, Hou Hsiao Hsien, 1998 |

The revelation of Chinese cinema since the beginning of the 1980s (a new generation in Hong Kong, the New Cinema in Taiwan, the 5th generation in China) has been the great event of these recent years. By delving into a pictorial tradition that stretches back over a millennium, the cinema of King HU, through its art of movement (playing on what is clear and what is out of focus), his sense of editing and rhythm in combat scenes, has ties with calligraphy and reconstitutes the ideogram, with its combination of thick and thin strokes. These figures that fluctuate on a blank background form a ballet that we also find in the films of WONG Kar-Wai, where calligraphy becomes choreography, a suite of mannered vanities in a dizzying eddy, but also in the works of Johnnie TO, whose hieratic silhouettes are drawn into another, more infernal round. China has a particular attachment to ancestral values (Confucianism), an art of detachment (Taoism), that one can feel in its painting and in its poetry but that is expressed in film in the work of HOU Hsiao-hsien through his singular manner of keeping distance, of bringing emotion to the surface by maintaining distance from faces, while at the same time telling stories according to a logic (“detour and access”) that breaks with traditional narrative style. If China is haunted by its recent history (Farewell My Concubine) and its current transformations (JIA Zhangke), it is undoubtedly Edward YANG with Yi Yi who has best succeeded in achieving this balance between present reality, marked by the influence of America in daily life (urban architecture, for example) and the traces of the Japanese occupation on the island, and the past reality, more diffuse, that springs out through the painting of emotions, so typical of the Chinese cinematic tradition (Spring in a Small Town, FEI Mu). The expression of emotion remains the most complex channel in Chinese cinema, its most mysterious aspect, whereas calligraphy, through its poetic abstraction, is its most accomplished visible aspect, astonishing in its virtuosity.

[All the films mentioned are in Competition, unless otherwise indicated: UCR for Un Certain Regard, HC for Out of Competition and SS for Special Screening]

* Charles Tesson is a film critic and historian

Photo credits Christophe L.