FRENCH CINEMA AND THE FESTIVAL DE CANNES

BY NOEL HERPE*

|

.jpg) |

| Martine Carol in Caroline chérie |

|

| Antoine et Antoinette, J. Becker |

|

| L’Amour d’une femme, J.Grémillon |

Who developed the notion of “French quality”? And who on earth would have believed that this prestigious label would end up being remembered as an outdated academic approach? In reality, French cinema after 1945 was not all that academic.

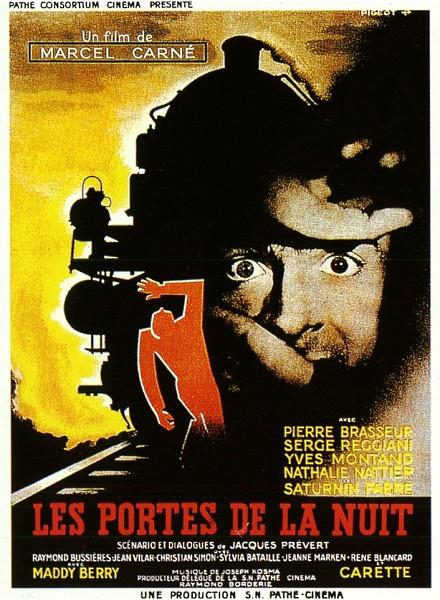

It was a worthy successor to the poetic realism of the pre-war period, to which it added a number of late blooms, all as beautiful and full of hopelessness as their predecessors: Les Portes de la Nuit (Marcel Carné, 1946) or Dédée d’Anvers (Yves Allégret, 1948). It also managed to integrate an Italian style of neo-realism, or even an English influence, with the great “docu-fictions” of the Resistance, accompanied by half-tone chronicles filmed by Jacques Becker (Antoine et Antoinette, 1947) or Jean Grémillon (L’Amour d’une Femme, 1953). It also had the ability to resuscitate myths: the myth of the Belle Époque, the idealised golden age of pre-1914 to where the great Hollywood defectors, such as Jean Renoir and René Clair, retreated. It was a cinema capable of inventing stars: in place of the ageing superstars of the 1930s (Raimu, Harry Baur, Jules Berry), younger, more glamorous actors arrived, who were better suited to the Utopian ideas of the Liberation. These were stars like Gérard Philipe in Fanfan la Tulipe (Christian-Jaque, 1951), Martine Carol in Caroline chérie (Richard Pottier, 1951) and other dreamlike creatures, who the ingenious Max Ophuls used as the very subject of his films.

|

Fanfan la Tulipe, Christian-Jaque, 1951

The demonstration of genius ruled supreme right into the 1950s, which later came to be thought of as a rather vapid period in French cinema. Genius scintillates in the works of Robert Bresson, whose “cinematographer” theory rejected the standard conventions of film and forced the spectator to watch and listen in new ways. Genius also slips into the works of Jacques Tati, who established a rigorous mechanism of burlesque to mock the shortcomings of the modern world (Mon Oncle, 1958). Intolerably excessive genius is present too in the works of Henri-Georges Clouzot, with the exception of those that were already constrained to the demands of the detective film genre (Quai des Orfèvres, 1947), or those that aimed to highlight the genius of another man (Le Mystère Picasso, 1955).

Mon oncle, Jacques Tati, 1958

Quai des orfèvres, Henri-Georges Clouzot, 1947

Above all, this post-war cinema identified with a very specific form that was no longer poetic in the least: naturalism. It was a naturalism derived from the literature of Zola and Simenon, authors who were cherished by the screenwriters of the day. This naturalism became the perfect cinematographic expression of the spirit of the times. Only naturalism, with its mixture of pessimism and repressed idealism, could call up the shadows of occupied France (La Traversée de Paris by Claude Autant-Lara, 1956), or describe the oppressiveness of a Fourth Republic in decline (André Cayatte’s ambitious legal series). Made by left-wing directors, these films tackled real taboo subjects, but restricted their boldness to the political arena. This limitation explains the legitimate impatience of a younger generation of filmmakers, new directors who emerged mostly from a review created in 1951 called Cahiers du Cinéma. Criticising the naturalist tendencies of their predecessors, they denied them their provocative taste for the natural in their writings (and then in their films).

La Traversée de Paris, Claude Autant-Lara, 1956

Jeanne Moreau in Ascenseur pour l’échaffaud directed by Louis Malle, 1957

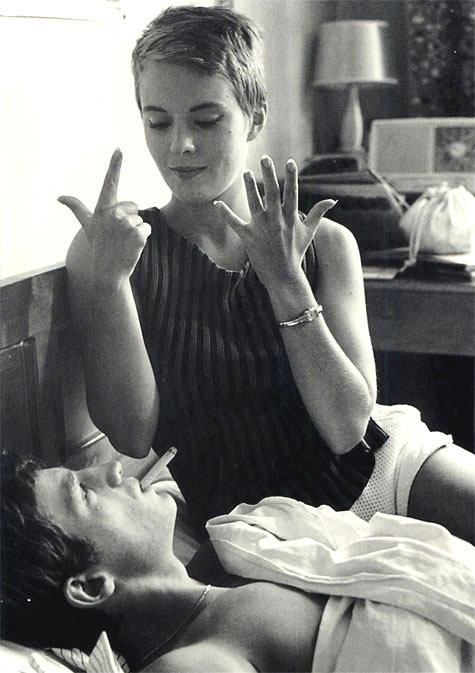

Les Quatre Cent Coups by François Truffaut (1959) and A Bout de Souffle by Jean-Luc Godard (1960) were the first films to spearhead this French “New Wave”. The major hallmarks of this new trend were filming outdoors with youthful actors who were allowed to improvise. But this renewal in the 1960s also gave birth to a more cerebral, stylised cinema in the films of Alain Resnais, who explored the mechanics of memory and collective representation (Hiroshima Mon Amour, 1959), and in the films of Agnès Varda and Jacques Demy, who reinvented the documentary and musical comedy genres.

Les Quatre cent coups, François Truffaut,1959

|

|

| A bout de souffle, Jean-Luc Godard, 1960 |

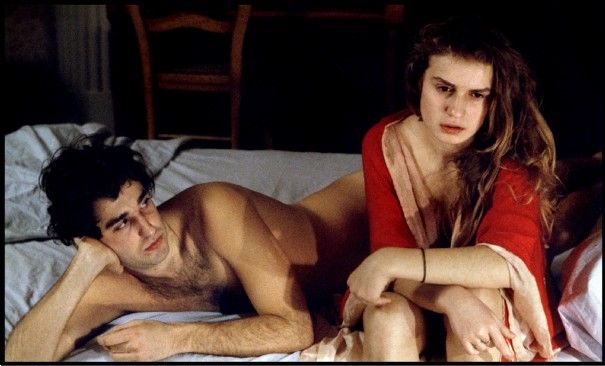

Truth be told, this New Wave (with its offshoots) only played an ephemeral role at the box office itself. However, its influence was enduring and international, and it imposed its “arthouse politics” and the faces of unforgettable actors like Jean-Paul Belmondo, Jeanne Moreau, and Catherine Deneuve for decades to come. It became permanently established as a school of thought, inspiring a whole range of traditions that emanated from its founding fathers. In this sense, one can identify a Truffaut tradition, featuring romantic subjectivity and effusive emotion, that has been brilliantly incarnated in each subsequent generation by figures such as Jean Eustache (Mes Petites Amoureuses, 1974), Léos Carax (Boy Meets Girl, 1984) and Arnaud Desplechin (Comment Je Me Suis Disputé… Ma Vie Sexuelle, 1996).

|

|

|

| Mes petites amoureuses Jean Eustache,1974 |

Boy Meets Girl Léos Carax, 1984 |

Comment je me suis disputé… Arnaud Desplechin, 1996 |

In the same manner, it is easy to distinguish the progeny of Demy today in the flamboyant novelistic style of André Téchiné or Christophe Honoré. Nevertheless, the ghost of naturalism is tenacious. At the heart of the New Wave, it was ironically reincarnated by Claude Chabrol, whose bourgeois chronicles were narrated in a chillingly detached style – one that earlier filmmakers, such as Clouzot or Duvivier, would not have disavowed.

|

La femme infidèle, Claude Chabrol, 1969

|

| A nos amours, Maurice Pialat, 1984 |

|

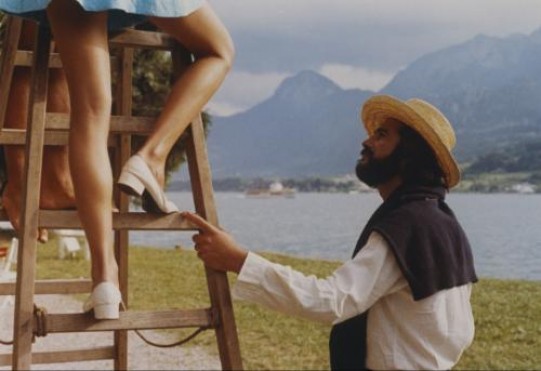

| Le Genou de Claire, Eric Rohmer, 1970 |

In the 1970s, naturalism was explored with extraordinary vigour in the works of Maurice Pialat, who finally gave true meaning to the expression “a slice of life”: a section of brutal reality, carved right from the flesh. More recently, naturalism has been extended by the works of Jacques Doillon (Le Jeune Werther, 1993) and Abdellatif Kechiche (L’Esquive, 2002), both chroniclers who explore the complete redefinition of French identity.

One could go on unravelling these lineages and derivations at great length, for example by demonstrating the persistent recurrence of “left-wing fiction” or feminine auto-fiction. One could also isolate the case of a filmmaker who has remained unique: Eric Rohmer. His works alternate contemporary cycles with costume drama films and he has never had to renounce his financial independence, or his puritanical hatred of artifice. What one encounters in all of these cases is a flexible relationship with reality, which actually constitutes the true continuity of French cinema, beyond the battles in Hernani and its obvious ruptures. Resistant to the fantastic genre or to the codes of comedy (with the exception of a tenacious craftsman like Jean-Paul Rappeneau), the author of French films essentially casts his view over the world around him, over the society of his peers and over his own personal history. In this great family that likes to tear itself apart, the offspring always remain Lumière heirs, to a greater or lesser extent.

Gérard Depardieu and Anne Brochet in Cyrano de Bergerac, JP. Rappeneau, 1990

France at Cannes

One of the missions of the first Festival de Cannes in September 1939 was to showcase French cinema more effectively. The Biennale in Venice, under the influence of Fascism, had not shown any favour to La Grande Illusion. However, it was not until 1946 that the first Festival actually took place and was able to showcase French films on the international scene. Although a balance had to be maintained between the cinematographic productions of various nations, it was rare in those early years for France not to appear on the list of award-winning films. The major beneficiary of this increased attention was a brilliant and multi-talented filmmaker, who was the incarnation of both a “politically committed” neo-realism and a certain continuity with the pre-war period: René Clément won awards in 1946 for La Bataille du Rail, in 1949 for Au-Delà des Grilles and in 1954 for Monsieur Ripois (but oddly, not for Jeux Interdits, which was screened on the fringe of the Competition, but went on to make the entire world weep).

La Bataille du rail, René Clément, 1949

Un condamné à mort s’est échappé, Robert Bresson, 1957

In successive years, the Cannes jury generally found itself rewarding works that did not enjoy a consensus of approval, such as Un Condamné à Mort s’est Échappé (Robert Bresson, 1957) or Mon Oncle (Jacques Tati, 1958). Challenged by the young François Truffaut, the French selection decided to include his Quatre Cents Coups in the 1959 selection – a historically ironic decision that did not escape the attention of Jacques Audiberti: “As the ultimate joke, the admirals are now cajoling the mutineer! (…) Waving his banner, the banished rebel is returning to his grateful country!”

To add another metaphor, it was mostly the “proletarian” foam of the New Wave that was commended by the Croisette: the foam from a port in lower Normandy, for instance, that was transformed into a beautiful vision by Jacques Demy (Les Parapluies de Cherbourg, 1964), or the foam from the beach of Deauville, romantically filmed by Claude Lelouch (Un Homme et Une Femme, 1966). In both cases, the charm of the music was a major factor in garnering votes from the jury in Cannes.

Les Parapluies de Cherbourg, Jacques Demy, 1964

Un homme et une femme, Claude Lelouch,1966

|

| Hiroshima mon amour, Alain Resnais, 1959 |

However, this period also witnessed many diplomatic incidents: in 1955, 1959 and 1966, films by Alain Resnais were withdrawn, including Nuit et Brouillard under pressure from Germany, Hiroshima Mon Amour under pressure from the United States and La Guerre est Finie under pressure from Spain, although André Malraux was able to maintain the official screening of Hiroshima. In 1966, the selection of Jacques Rivette’s film La Religieuse was highly contested, but had Malraux’s blessing yet again. It was only after May 1968 and the mini-coup of a handful of French filmmakers that the Cannes competition became less bound to protocol and more open to innovative and current cinematic ideas.

La Religieuse, Jacques Rivette, 1966

However, the dual demands of a festival that is both international and national meant that this was not an easy task to accomplish. It meant a new division of responsibilities, which was initiated in the 1970s by the Delegate General Maurice Bessy and perpetuated by his successor Gilles Jacob from 1978 onwards. From 1983, the French selection (which had previously been closely monitored by the Ministry of Culture) was delegated to an independent committee that was to send three or four hand-picked films to Cannes each year. An out-of-competition section was simultaneously created (“Un Certain Regard”) along with a prize for the best film (the Caméra d’Or), followed by the Cinéfondation later on, which would help to spot and promote more meticulous filmmakers, such as Raymond Depardon, Pascale Ferran, Jean-Marie Straub, and many new arrivals.

Van Gogh, Maurice Pialat, Competition 1991

Little by little, this eclectic approach helped mitigate the debates that French cinephiles had always enjoyed indulging in: in 1973, the Grand Prix awarded to La Maman et La Putain by Jean Eustache was booed, as was L’Argent by Robert Bresson in 1983. In 1987, the Palme d’Or awarded to Sous le Soleil de Satan by Maurice Pialat was also contested. But such spectacles are also what feed the myths surrounding any festival. After the series of uncontested honours that have been bestowed on Entre les Murs (Laurent Cantet, 2008), Un Prophète (Jacques Audiard, 2009) and Des Hommes et Des Dieux (Xavier Beauvois, 2010), is there perhaps some nostalgia for the taint of scandal?

Entre les murs, Laurent Cantet, Palme d’or 2008

Un prophète, Jacques Audiard, Grand Prix 2009

Des hommes et des Dieux, Xavier Beauvois, Grand prix 2010

>> DOWNLOAD A PDF OF THE ARTICLE

* Noël Herpe is a film writer and historian.

The Festival de Cannes would like to thank the authors for contributing for free.