INTERVIEW – Abbas Kiarostami : “The quest for innovation has to take place in short films and in a director’s first films”

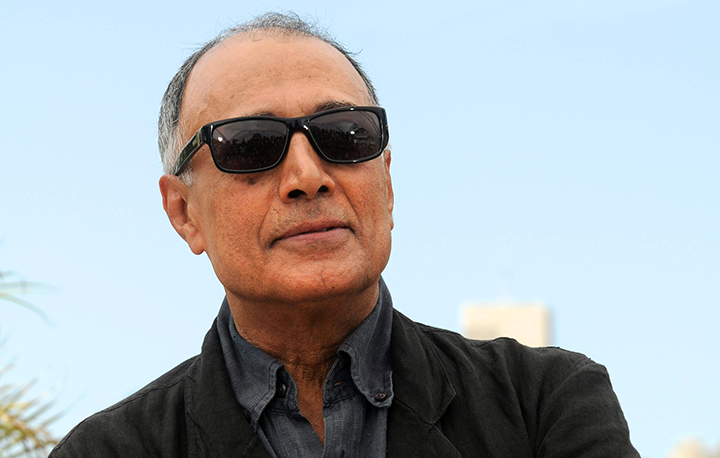

Poet, painter, photographer… At the age of 73, Abbas Kiarostami is a director whose talent is not only expressed on screen, although it is through his films that the Iranian director has been consecrated in the eyes of the world. A major figure of free and innovative “cinéma d’auteur” and a member of the Iranian “nouvelle vague” that appeared in the seventies, he won the Palme d’Or in Cannes in 1997 for Taste of Cherry (Ta’m e guilass). This year, he is President of the Cinéfondation and Short Films Jury. He recalls his first ventures in film.

What kind of a young director were you?

I am inclined to say that the only point I can see now, at my age, that I had in common with young filmmakers of the day was that we were all young. I had not studied film. I did not see it as my vocation. I studied painting but I did not end up as a painter. Then at some point I realised that the cinema would be a refuge for me and that film would be the medium in which I could best express myself.

What are your memories of your first experiences behind the camera?

My first film was extremely difficult to make. As luck would have it, it was a big hit and was recognised. For me, that didn’t mean that I would become a filmmaker. I believed that this chapter was over and that I would not make any more films. Nevertheless, I did make more films, and then I made even more of them. When I made my first feature film, I told myself that I should take stock of the fact that being a filmmaker was my job. For this first film, I encountered two types of audiences: one was composed of people who loved my films and the other, larger group did not like them at all. That is still true today.

What qualities does a first film need for it to be a success?

What convinced me that my first film was a success was that it was recognised in a festival and that it was selected for the award for best short film. For me, that was the criterion of success. Today, in retrospect, I do not think that a good film is a film that wins a prize. Nor do I think that a good film is one that draws a big audience or that gets positive reviews from the critics. I think that the determining criterion is its sustainability. A good film is one that lasts, that history deems worthy of staying with us. I do not remember who set this time frame at thirty years. Whoever it was said that after thirty years we can judge whether a film is sustainable, whether we even know if it still exists or if it has disappeared.

What importance do you attach to short films in the career of a filmmaker?

They are extremely important because they give the director an opportunity to be bold and to experiment. The personality of a director is felt very strongly in his or her short films. In feature films, the producer and the financing inevitably cast a long shadow, as well as audience taste. No director can ignore these two factors. As a result, the short film is more important because it is so personal. The quest for the avant-garde, for innovation, has to take place in short films and in a director’s first films.

Abbas Kiarostami © FIF / CB

Tell me about Iranian film. Do you feel it is in a healthy condition?

To take a snapshot of Iranian cinema today, you have to make an extension between two types of films. On the one hand, there is the State cinema, financed by the authorities. In Iran, there are a number of filmmakers who work thanks to the State and for the State. I don’t think much about them and I don’t expect much of them because they these filmmakers are only known in Iran. Their films are meant for an extremely local and targeted consumption. Then there is an independent cinema that is flourishing. Today, unknown filmmakers are arriving from the most far-flung provinces of Iran. Thanks to the opportunities offered by new technologies and small digital cameras, they are delivering very high quality films. My hope is embodied in these people.

What is left of the Iranian New Wave that you were part of?

You will have to ask new generations to answer this question. They are the ones who could tell you what they have retained from it and whether there is a legacy, an influence. One thing is certain: the cinema and filmmakers of the time were much freer than they are today in Iran. We had the Kānun, this institute for the development of children and young people. Its directors gave us carte blanche and they did not interfere in any way in our work. This is quite a remarkable process that had an obvious impact on our work. However it seems to me that this New Wave has never broken. These filmmakers from the outlying provinces that I referred to just keep on renewing it constantly.

What do you still expect from cinema?

I don’t expect anything. Expectation belongs to young people. But without expecting anything, I keep working. The essence of film is in the production of images. There is never a month that goes by that I don’t make a short film, a little video piece or a photograph. Perhaps what I expect from cinema today is to know that I have made a new image when I fall asleep at night. Like a fisherman who always hopes to catch a fish when he casts his nets.

Interviewed by Benoit Pavan