The Scope format, created in the 1950s, based on an invention by the French astronomer Henri Chrétien, is an anamorphic lens that allows filmmakers to capture and present panoramic images on the big screen. Unlike traditional formats, it opened up a new visual horizon of an unprecedented scope to directors. In France, the first film to officially demonstrate this process was Marcel Ichac’s Nouveaux Horizons (shot in CinemaScope). It was screened at Cannes in 1954, ahead of Henry Koster’s feature film The Robe. The wide screen offers a striking level of immersion. It brings the distant closer and plunges the spectator into grandiose landscapes and scenes of unprecedented depth. “The impression of depth disappears when the camera is static.” (Jean-Jacques Meusy, La Recherche n°359)

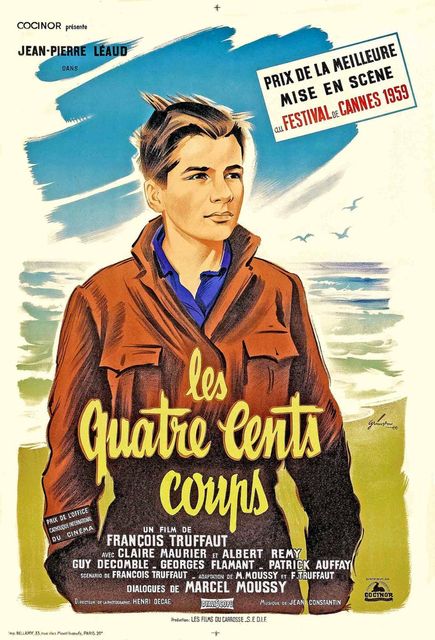

New Wave filmmakers like François Truffaut also embraced this innovation to serve as part of their aesthetic revolution. Truffaut’s first feature film Les Quatre cents coups (The 400 Blows) (Award for Best Director in 1959) was shot by Henri Decaë in black and white DyaliScope. The use of a wide screen made it possible to accentuate the narrowness of the apartment belonging to the parents of the protagonist, Antoine Doinel. “The Scope provides a greater impression of narrowness for real sets. Thus, in Les Quatre cents coups (The 400 Blows) the tiny sets where we shot kept their proportions, whereas the normal format would have deformed them.” (Henri Decaë – source: Les Directeurs de la photo et leur image by Christian Gilles)