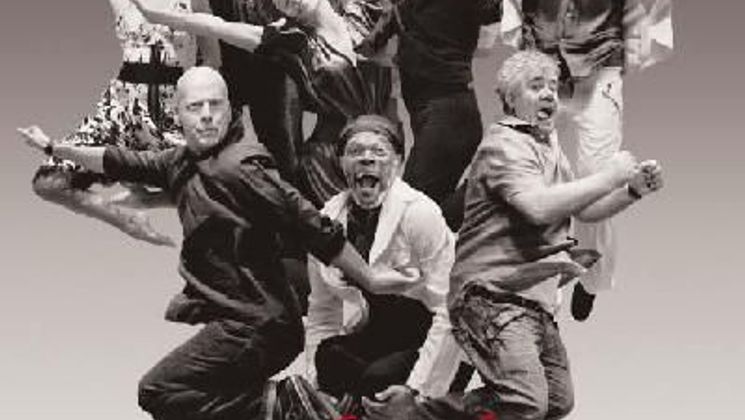

Master Class: Sergio Castellitto

The first of the three Masterclasses in filmmaking offered at this year’s Cannes Festival was given by Italian actor and director Sergio Castellitto, the hero of such films as My Mother’s

Smile and Who Knows, both screened at past Festivals. In response to questions from Elisabeth Quin, the actor described his career and indulged in some speculation about

the trade, with illustrations from his films. He then answered questions from the audience – which included such notable figures as Michel Piccoli and Marco Bellocchio, members of the

Cannes jury who have both worked with Sergio Castellitto. Excerpts follow.

On Buster Keaton: “I admire the way he uses existential anxiety to create a bond with the audience. He was the actor who taught me that I needed the courage to stand still, to do nothing, and

to express something using my gaze, for example, instead of a movement.”

On the start of his career: “In my case, experience stimulated the calling: the more I acted, the more I loved it. In the beginning, I didn’t want to be an actor. I believed that I lacked the

artistic aptitude for it, but perhaps I was actually fearful of discovering this aptitude in myself. My first teacher, the director Otomar Krejca, taught me something I’ve never forgotten: acting

is also allowing the other to act for you. It’s a bit like judo; you make use of the energy of the other.”

On the importance of the body: “I always start with the body, with behavior. The most intelligent technique an actor can adopt is to stop thinking. The body has its own

intelligence.”

On the European school of acting, compared to the American one: “We have an age-old theatrical tradition. We prefer to show, rather than to be. The American tradition is much newer, and they

are more naturalistic. I have never thought that it was better for an actor to cry for real. I believe in representation.”

On acting in French: “The problem with acting in a different language is that the first time, your voice changes. It gets higher. It took time for me to adjust my voice to my

body.”

On his dual role as actor and director: “When I am interpreting a role, I am the violin soloist, serving the composer’s score. At one point, I wanted to have a go at the megalomaniac

ambition: constructing the story. It was clear to me that the director, not the actor, is the one subject to megalomania. The actor is just a wild horse with intelligence. He must be intelligent,

to place himself at the director’s disposal, but he must also be intelligent enough to betray the director’s intentions, without it being noticed… Actors know they are behind characters, and

directors are behind cameras. Each has his/her own Trojan horse. To act is to give an opinion about things. But not to act is the same. Next to the column of your résumé that says

what you’ve done, there should be a column that says what you have not done…”

On Jacques Rivette: “I met him in a bar on the Champs-Elysées. He gave me a single page, and told me that I’d be given the script later. It wasn’t true; there was no such thing as the

script… When an actor asks him a question, he always replies, ‘I don’t know.’ It took me a long time to understand that what he wants is to discover it with the actor, day by

day.”

On My Mother’s Smile: “The first time, I didn’t understand a word of the script, but I was eager to work with Bellocchio. It’s one of the most spiritual films made in Italy

these past ten or fifteen years, with a sense of ethics. I am a religious man, and Marco is not, but we struck a wonderful balance. It’s a film that speaks of our country and its sociology

symbolically.”

Photo Copyright Anne-Laure Bigot