BRAZILIAN CINEMA AND THE FESTIVAL DE CANNES

BY PAULO PARANAGUA*

Since the arrival of Edison and the Lumière brothers’ invention in Rio de Janeiro, film has served as an expression of the triangular relationship which Brazilian culture has constantly maintained with Europe and the United States. During the so-called “belle époque” – the early years of the twentieth century – all eyes were focused on the latest trends coming out of Paris and the Film d’Art, as well as on Italian divas.

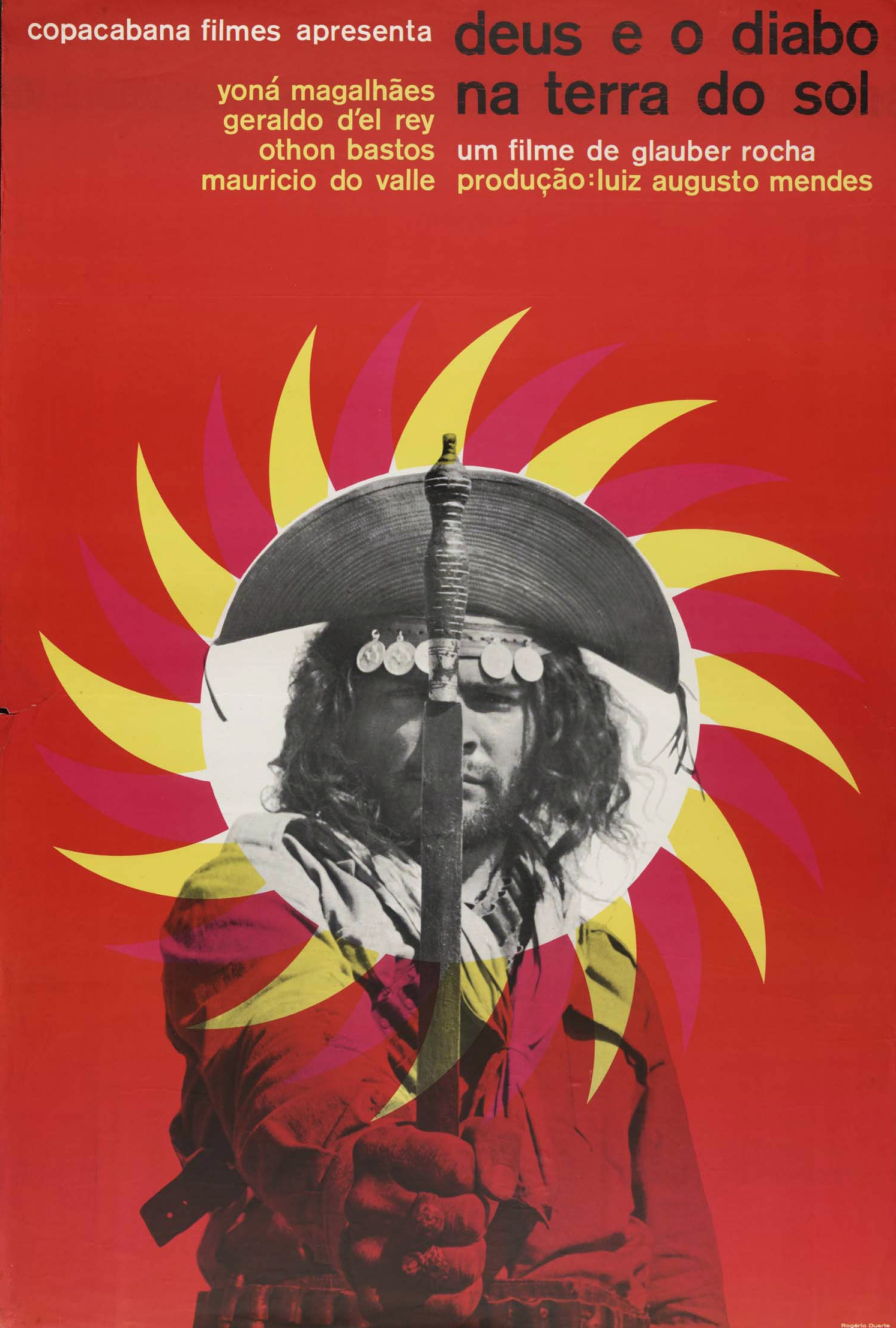

The First World War slowed this transatlantic flow and favoured the introduction of the Hollywood Majors. Brazil’s most important film director during the first half of the century, the self-taught Humberto Mauro from rural Minas Gerais, assimilated the new visual language by deconstructing films by King Vidor and Henry King. A complex personality to whom the Festival de Cannes paid tribute in 1982, Mauro was both a “modern film director” with an interest in technology and electronics, and a conservative attached to the rural and patriarchal world threatened by rapid urbanisation.

The First World War slowed this transatlantic flow and favoured the introduction of the Hollywood Majors. Brazil’s most important film director during the first half of the century, the self-taught Humberto Mauro from rural Minas Gerais, assimilated the new visual language by deconstructing films by King Vidor and Henry King. A complex personality to whom the Festival de Cannes paid tribute in 1982, Mauro was both a “modern film director” with an interest in technology and electronics, and a conservative attached to the rural and patriarchal world threatened by rapid urbanisation.

Upon leaving his native province to move to Rio de Janeiro, the country’s capital at that time, Mauro drew on a mix of influences and often borrowed from European cinema. His masterpiece, Ganga Bruta (1933),  is a brilliant and intense hybrid film lying somewhere between silent cinema and a babbling talkie. Mauro would continue to find inspiration for his work in Europe while at the head of the National Institute of Educational Cinema (INCE). The European debate on the relationship between cinema and education, and the activities of the Instituto Luce in Italy did not escape INCE, which itself promoted the production of high-quality documentaries. While at INCE, Mauro filmed the series, “Brasilianas”, focusing on popular songs and folk melodies, in which he gave free rein to his lyricism.

is a brilliant and intense hybrid film lying somewhere between silent cinema and a babbling talkie. Mauro would continue to find inspiration for his work in Europe while at the head of the National Institute of Educational Cinema (INCE). The European debate on the relationship between cinema and education, and the activities of the Instituto Luce in Italy did not escape INCE, which itself promoted the production of high-quality documentaries. While at INCE, Mauro filmed the series, “Brasilianas”, focusing on popular songs and folk melodies, in which he gave free rein to his lyricism.

By the end of the silent era, the local market was dominated by Hollywood films, but that did not stop the European avant-garde from projecting their aura onto a filmmaking elite. Two Hungarians living in Brazil, Rodolpho Rex Lustig and Adalberto Kemeny, emulated Walther Ruttmann in their documentary, Sao Paulo, A Symphonia da Metropole (Sao Paulo, A Metropoloitan Symphony, 1929). Mario Peixoto, writer and director of the truly unique work, Limite (Limit) (1930), which is considered the pinnacle of Latin American silent cinema, employed bold experimental techniques. Despite being disparaged by Glauber Rocha, who had not even seen it, Limite is, along with Mauro, representative of the immense hopes placed by these Brazilians in cinema as the key to revealing inner landscapes and the vast horizons of their time.

|

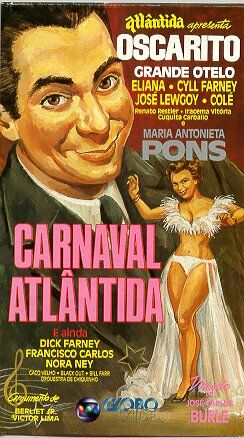

The talking-picture revolution coincided with the rise of cultural nationalism and the golden age of populism, embodied by the figure of Getulio Vargas (Head of State from 1930 to 1945, and then again from 1950 to 1954). During this period, musical comedies borrowed their melodies from carnival and their burlesque acting from variety shows. Local productions enjoyed unheard-of success with the general public, who voiced their satisfaction noisily in cinemas . The actors Oscarito and Grande Othello became stars in their own right. These “Chanchadas”, which were looked down on by the elite for a long time, sometimes used allegory and parody to focus on the typically Brazilian habit of swinging between the United States and Europe, and between the new popular culture of the masses and traditional erudite culture. Carnaval Atlantida (José Carlos Burle, 1952) and De Vento Em Popa (Carlos Manga, 1957) are classics today, thanks to the rereading of history favoured by the late Paulo Emilio Salles Gomes, the soul of Brazilian Cinema in Sao Paulo.

. The actors Oscarito and Grande Othello became stars in their own right. These “Chanchadas”, which were looked down on by the elite for a long time, sometimes used allegory and parody to focus on the typically Brazilian habit of swinging between the United States and Europe, and between the new popular culture of the masses and traditional erudite culture. Carnaval Atlantida (José Carlos Burle, 1952) and De Vento Em Popa (Carlos Manga, 1957) are classics today, thanks to the rereading of history favoured by the late Paulo Emilio Salles Gomes, the soul of Brazilian Cinema in Sao Paulo.

After the Second World War, Europe was characterised by both classicism and renewal. Paradoxically, the first serious attempt ever made to adapt the Hollywood model to Brazil was inspired by the Cinecittà. Indeed, the great Vera Cruz Studios (1949-1954) were set  up by a member of Sao Paolo’s new Italian-Brazilian middle class: Alberto Cavalcanti. He arrived on this scene like the prodigal son, having agreed to work in his native country for the first time in a career that he began in France and developed in Great Britain, marked by innovation and tasteful eclecticism. Despite notching up local and even international successes, the Vera Cruz went into liquidation after only five years, crippled by the harsh economic reality of the film industry.

up by a member of Sao Paolo’s new Italian-Brazilian middle class: Alberto Cavalcanti. He arrived on this scene like the prodigal son, having agreed to work in his native country for the first time in a career that he began in France and developed in Great Britain, marked by innovation and tasteful eclecticism. Despite notching up local and even international successes, the Vera Cruz went into liquidation after only five years, crippled by the harsh economic reality of the film industry.

At around the same time, a challenge also came from Italy in the form of neorealism. This genre would come to dominate debates at film societies and in magazines, gaining more or less strong support from communists and Catholics alike, before being embodied by the figure of Nelson Pereira dos Santos: Rio 40° (1955) and Rio Zona Norte (Rio, Northern Zone, 1957) both directed by dos Santos, along with O Grande Momento (The Grand Moment, 1958) produced by dos Santos and directed by Roberto Santos in Sao Paulo. These films represented an alternative form of expression and production for the new generation.

Next, the French movements known as Le Jeune Cinéma (Young French Cinema) and La Nouvelle Vague (The New Wave) would in turn become known across the continents, prompting exceptionally fruitful dialogue among directors from diverse countries. And a similar relationship to the transatlantic triangle would come to exist with Japan: Japanese films went down a storm with Brazilian cinema-goers, who enjoyed the existence of a strong Japanese community in Sao Paulo. “Cinema Novo” thus interacted on an equal footing with formulas and techniques from the United States, Europe and elsewhere. This collective movement brought together figures as diverse as Glauber Rocha, Ruy Guerra, Joaquim Pedro de Andrade, Leon Hirszman, Carlos Diegues and Eduardo Coutinho.

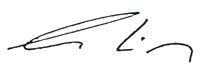

MEMORIES OF CANNES BY CARLOS DIEGUES

“ Brazilian Cinema Novo invented cinema for a country and a country for the cinema. When the movement instigated by my generation was born in the early 1960s, Brazil did not yet have an image of its own and was unaware of the ability film had to act as an audiovisual mirror. We gradually created this image as we developed modern Brazilian cinema. The 1964 Festival de Cannes played a decisive role in sparking international interest in this new cinema, which represented the first film-making movement to come out of what was then referred to as the Third World. Two films stood out in the Official Selection: “Vidas Secas” (Barren Lives) by Nelson Pereira dos Santos and “Deus e o diabo na terra do sol” (Black God, White Devil), by Glauber Rocha. In that same year, my first film, “Ganga Zumba”, which was screened during the Semaine de la Critique, also attracted attention.From that point onwards, thanks to Cannes and the French press, Brazilian Cinema Novo gained worldwide recognition as a leading example of the radical changes that the film industry was undergoing during that decade. I was 23 years old back then and those days at Cannes were full of discovery, excitement and awe: I had the wonderful feeling of being welcomed into a universal family that I had never imagined belonging to one day. It wasn’t just my first feature film: it was also my first trip to Europe, my first international festival and my first time wearing a dinner jacket (a hired one, of course!). And I was at Cannes! Yes, CANNES!

Carlos Diegues, November 2010 |

For the first time, the flow of influence changed direction, with Brazilians inspiring other directors in Latin America and beyond: after all, didn’t Miklos Jancso’s sequence shots and circular tracking come from Glauber Rocha? What did it matter anyway? Cinema had never been so cosmopolitan and open to external influences; images had never circulated so quickly, nor been so influential… At least, that was the panorama in the world of special screenings at film festivals, which started to sprout up all over the place, as if by magic. As for the general public, spectators were not on the same wavelength yet. In actual fact, the general public had fragmented and, from that point on, several types of audience would exist. Two factors explaining why this division was deeper than in other parts of the world were the profound inequalities existing in Brazilian society and the purely commercial nature of television.

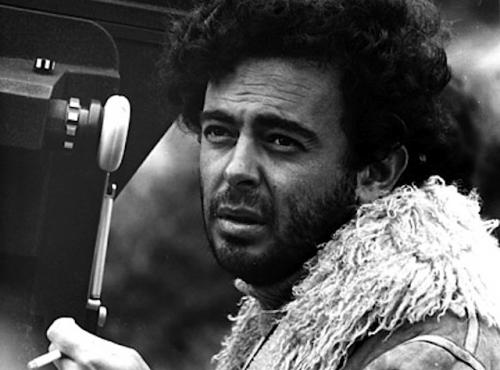

Glauber Rocha, Black God, White Devil, In Competition, 1964

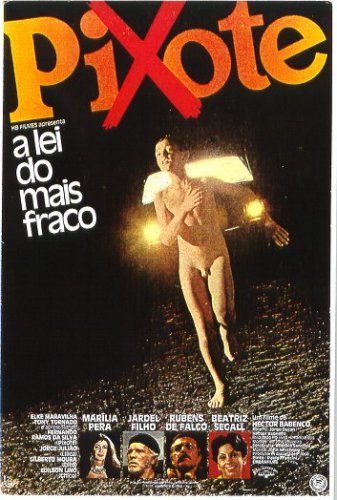

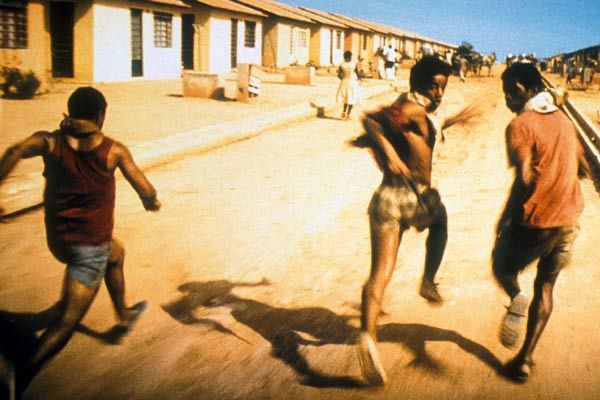

There were pre- and post-“Cinema Novo” eras. Modernity shook things up, even though production methods still lagged behind. The Embrafilme period (1969-1990), named after the state-funded production and distribution company that was swamped with “Cinema Novo” directors at the height of the military regime was, without doubt, the most prolific period in Brazilian filmmaking history. In 1980, production reached record heights (103 feature films) and some Brazilian films even competed with American ones at the box office. Héctor Babenco’s Pixote (1980) was sold to more than thirty countries. However, the “model” remained fragile since it was based on independent production supported by the State and it had to compete with a powerful television channel. While the number of cinemas fell, TV Globomade its way into everyone’s home. The “civilization of the image” prevailed. Audiovisual fiction shaped people’s behaviour and minds. The melodrama and “Chanchada” formerly employed by filmmakers would now become commonplace on the small screen. And all this to the detriment of cinema, which would soon become confined to audiences at shopping centres.

There were pre- and post-“Cinema Novo” eras. Modernity shook things up, even though production methods still lagged behind. The Embrafilme period (1969-1990), named after the state-funded production and distribution company that was swamped with “Cinema Novo” directors at the height of the military regime was, without doubt, the most prolific period in Brazilian filmmaking history. In 1980, production reached record heights (103 feature films) and some Brazilian films even competed with American ones at the box office. Héctor Babenco’s Pixote (1980) was sold to more than thirty countries. However, the “model” remained fragile since it was based on independent production supported by the State and it had to compete with a powerful television channel. While the number of cinemas fell, TV Globomade its way into everyone’s home. The “civilization of the image” prevailed. Audiovisual fiction shaped people’s behaviour and minds. The melodrama and “Chanchada” formerly employed by filmmakers would now become commonplace on the small screen. And all this to the detriment of cinema, which would soon become confined to audiences at shopping centres.

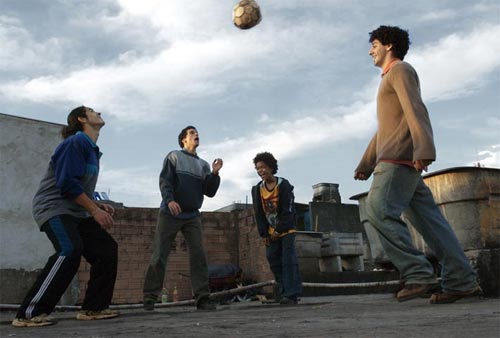

After all but disappearing, Brazilian cinema managed to rise from its ashes thanks to support often received from the United States or Europe. Another generation found a voice: Walter Salles and his brother, Joao Moreira Salles, or the documentary maker Fernando Meirelles and José Padilha. Some of these directors maintained a dialogue with the “Cinema Novo”, while others preferred to start afresh. Globalisation would henceforth be on everyone’s mind. With the Sundance Institute, the Cinéfondation or Ibermédia, a new triangular relationship would guarantee the continuity of Brazilian films into a new century marked by an unexpected rise in the number of cinemas.

|

|

|

|

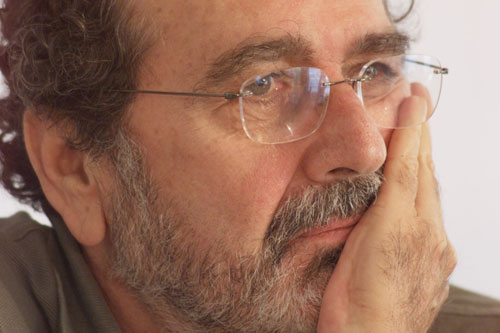

Walter Salles, J. Baldasserini |

Fernando Meirelles, R.R. Silvia, A. Rodrigues City of God, 2002 © AFP |

|

|

|

Brazil at Cannes

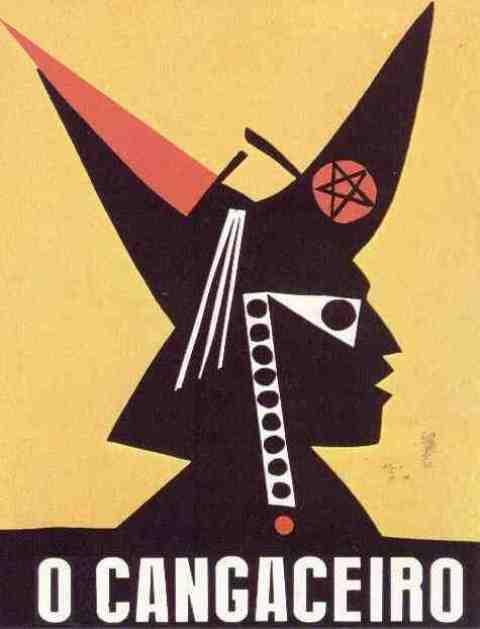

Vera Cruz Studios’ biggest box-office hit, O Cangaceiro (The Bandit) directed by Lima Barreto, was named the best adventure film at the Festival de Cannes in 1953. In 1962, O Pagador de Promessas (The Given Word) directed by Anselmo Duarte was awarded the Palme d’Or, probably one of the most controversial in the competition’s history. This work of transition between the old and the new did not go down very well with the “Cinema Novo” generation, even though the Croisette would come to serve as a platform for them to showcase their work.

%20(1961)%2002.jpg) |

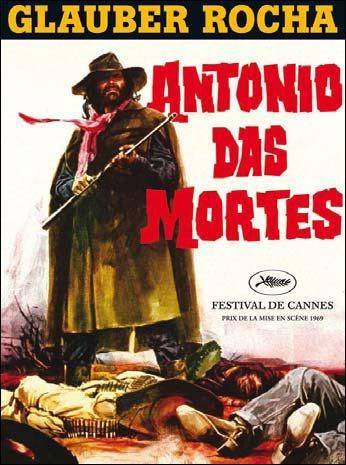

It would be there that, in 1963, Vidas Secas (Barren Lives) directed by Nelson Pereira dos Santos would charm the public and be awarded the OCIC prize. And it is there, too, that Glauber Rocha would present, Deus e o diabo na terra do sol (Black God, White Devil, 1964) and Terra em transe (Entranced Earth, 1967), before going on to win the Best Director Award for Antonio das Mortes (Antonio of the Dead) in 1969 followed by a special jury prize for the short film, Di Cavalcanti, in 1978. Subsequently, the cartoon, Meouw (Marcos Magalhaes, 1982), would also win the Best Short Film Award.

|

The Critics’ Week and Directors’ Fortnight took up the torch thanks to leading lights as effective as Pierre Kast. Twenty years after Vidas Secas, Nelson Pereira dos Santos would be carried down the stairs of the old Palais by admirers of his FIPRESCI award-winning film, Memorias do Carcere (Memories of Prison, 1984).

In 1986, the young Fernanda Torres won the award for best female actress for Eu Sei Que Vou Te Amar (Love me Forever or Never) directed by Arnaldo Jabor. In so doing, she signalled the arrival of a new generation of directors on the scene.

|

|

|

| O Cangaceiro (The Bandit), L. Barreto, In Competition, 1953 |

Arnaldo Jabor, Thales Pan Chacon, Lauro Escorel, |

Vidas Secas (Barren Lives) , N. Pereira dos Santos, |

* Paulo Paranagua is a journalist and film historian.

The Festival de Cannes would like to thank all the writers for their free contributions.