QUEBEC CINEMA

EXIST, WHATEVER THE COST

BY HELEN FARADJI*

Since the very beginning, cinema in Quebec has faced two considerable challenges: successfully asserting its own identity and doing so by creating a loyal audience.

|

|

|

| Albert Tessier |

The omnipotent Church avoided it like the plague. The five elections between 1936 and 1956 with Maurice Duplessis as Prime Minister, established a climate of Great Darkness which was ill-suited to any creative experimentation. American neighbours simply included it in their own domestic market. Yet for early Quebec cinema, the simple fact of existing, albeit in its most inoffensive form (its main films being those by the priest Albert Tessier and the abbot, Maurice Proulx, which proudly depicted the values of a good, submissive people, nature and rural life), seemed an achievement in itself.

However, while the Government of Canada established the National Film Board (NFB) in 1939, at the heart of which the animation department led by the brilliant Norman McLaren rapidly gained ground, a neglected industry attempted to free itself by tapping into the great successes of cultural heritage led by international directors (long live colonisation!). Amongst these directors (which included the French filmmaker, Paul Gury, who produced Un homme et son péché – A Man and his Sin – 1949, and Séraphin, 1950), was Fédor Ozep, a pioneer of Soviet cinema who directed Whispering City / La Forteresse (The Fortress) (1947), a police drama which was filmed simultaneously in both French and English language versions and had two different distributors! A historical curio, but also a symbol of the questions which would, from that point onwards, be associated with the growing Quebec film industry: should the American or the French market be targeted? Should films be shot in the local French or international French, or even in English? How could these differences be managed?

|

|

|

|

|

| Claude Jutra |

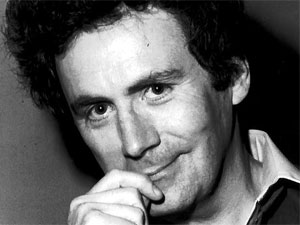

In 1948, an answer began to emerge. Written by the painter, Paul-Émile Borduas, the Refus global, a socio-political-artistic manifesto, united French-speaking artists and above all demanded the right to creative freedom. Other manifestations expressing this same desire appeared, such as the first short film by a young Claude Jutra, aged just 18 years old, which he filmed with his friend Michel Brault: Le Dément du lac Jean-Jeunes. Even mass-market productions, such as Tit-Coq directed by René Delacroix and Gratien Gélinas, started to assert their Quebec identity ever more clearly. Quebec cinema seemed to be ready to emerge from its chrysalis.

Whilst the NFB was established in Montreal in 1956, and film clubs and magazines were created, the effort underwent a transformation in 1958 when Michel Brault and Gilles Groulx directed Les Raquetteurs (The Snowshoers). Although they did not know it, the film was a pioneer of the Direct Cinema movement: it embodied this young form of cinema, which was confident and full of a real sense of national conscience, and was also present in Golden Gloves directed by Gilles Groulx and La Lutte (Wrestling) directed by Michel Brault, Claude Jutra, Marcel Carrière and Claude Fournier. Using a light, mobile camera, filmed in synchronous sound and capturing real-life, unique events, young Quebec cinema refused to educate or set an example. It aimed to stay loyal to the reality of a society undergoing great change. It was “film that claimed to distance itself from commercial success in in order to serve as the mouthpiece of real people and not pander to the dreams of the audience”, as documentary filmmaker Pierre Perrault put it perfectly in Caméramages.

Making the most of the revolutionary air that seemed to be inspiring young directors all around the world, a handful of filmmakers put Quebec on the map in moving images, while the Quiet Revolution created an atmosphere conducive to change and made it possible to assign the adjective “Quebec” as opposed to “French Canadian”. Some people credit the beginnings of this socially engaged form of cinema to the sublime documentary by Arthur Lamothe, Bûcherons de la Manouane (Manouane River Lumberjacks) (1962), others to Jutra with À tout prendre (Take It All) and his discourse on identity, racism, homosexuality and abortion (in 1963!). Others quote Pour la suite du monde (The Moontrap) by Pierre Perrault and Michel Brault, the first Quebec entry In Competition at the Festival de Cannes, or Le Chat dans le sac (The Cat in the Bag) by Gilles Groulx, who described the then current situation by depicting the end of a love affair between a francophone and an anglophone. Nonetheless, this burst of energy did not escape the interest of the rest of the world, with the Cahiers du Cinema even dedicating a special edition to Quebec cinema in March 1966. The mood of the time was also one of emerging feminism, the NFB opened its doors to women and created a studio dedicated to them, at the instigation of Anne Claire Poirier (De mère en fille (Mother-To-Be), Mourir à tue-tête (A Scream from Silence) and Il y a longtemps que je t’aime).

Yet, as in any good film, the honeymoon period did not last long. Although the Expo ’67 and the repertory cinemas were encouraging the boldness of this new cinema, censorship became the preferred instrument of control. Originally religious in nature, censorship became political, and despite allowing the booming popular cinema to be coloured by light-hearted eroticism (Valérie by Denis Héroux received unbelievable success in 1969, as did Deux femmes en or (Two Women in Gold) by Claude Fournier the following year), the October Crisis in 1970 solidified tensions between Quebec Nationalists and Canadian Federalists and intensified its severity. In 1971, the documentary On est au coton (Cotton Mill Treadmill) directed by Denys Arcand was consequently banned. Cap d’espoir by Jacques Leduc, 24 heures ou plus… by Gilles Groulx, Un pays sans bon sens! ou Wake up, mes bons amis!!! by Pierre Perrault also fell victim to the same fate. Yet filmmakers were inspired by the climate of agitation that was all around them: Réjeanne Padovani by Denys Arcand explored the behind the scenes of corrupted power and Les Ordres (Orders) by Michel Brault (Best Director Award Ex-aequo at Cannes in 1975) was based on the testimonials of people wrongly imprisoned during the crisis in order to better marry the assets of Direct Cinema with the new force of Quebec fictional cinema. International attention was also received by Claude Jutra for Mon Oncle Antoine (My Uncle Antoine) which reaped 21 prizes from around the world and established one of the recurrent themes of Quebec cinema: the absent father. Haunting and essential viewing, it would later influence the magnificent Bons débarras (Good Riddance) by Francis Mankiewicz.

Final scene of Orders directed by Michel Brault

Trailer for My Uncle Antoine directed by Claude Jutra

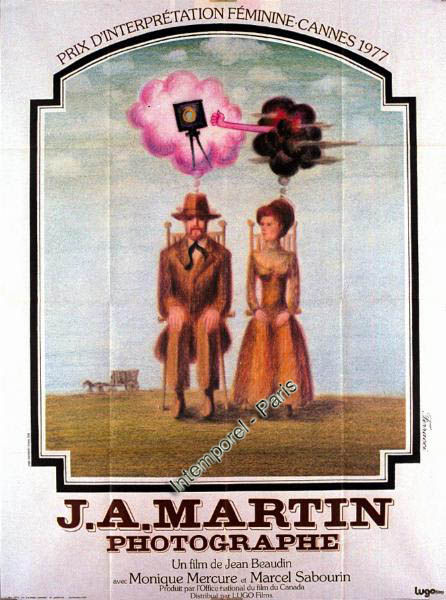

Indeed, Jutra was not alone in his success: Gilles Carle burst onto the scene at Cannes with Le Viol d’une jeune fille douce (The Rape of a Sweet Young Girl) (1968), La Vraie nature de Bernadette (The True Nature of Bernadette) (1972) and La Mort d’un bûcheron (Death of a Lumberjack) (1973) which launched Carole Laure’s acting career and confirmed the special status of filmmakers in France. In 1970, the prolific Jean Pierre Lefebvre saw three of his films (La Chambre blanche (The House of Light), Mon amie Pierrette (My Friend Pierrette) and Q-bec my love) selected for the Director’s Fortnight at Cannes. L’Eau chaude, l’eau frette (A Pacemaker and a Sidecar) (1976) by André Forcier was awarded the Press Grand Prix at Chamrousse and impressed the Jury’s President, Romain Gary. The amazing animated filmmaker, Frédérick Back, received his first Oscar for Crac! and Monique Mercure was awarded, ex-aequo, the Best Actress Award at Cannes for her role in J.A. Martin photographe (J.A. Martin Photographer) by Jean Beaudin. Quebec cinema was burning bright, everywhere, that is, except in Quebec.

Trailer for Death of a Lumberjack directed by Gilles Carle

|

|

|

Was this due to unfair competition from television? Or widespread indifference? The fact remains that Quebec audiences were abandoning Quebec film. To solve this problem, the industry settled on the sure values of heritage, via big-budget co-productions destined for both cinematic and televisual release. Although Les Plouffe (The Plouffe Family) by Gilles Carle came out on top, others such as Le Matou (The Alley Cat) or Bonheur d’occasion (The Tin Flute) displayed the limits of this type of luxury television-cinema. This status quo was, however, suddenly interrupted in 1986, by the surprise success of Déclin de l’empire américain (The Decline of the American Empire) directed by Denys Arcand. This film perfectly combined the author’s vision: box-office success and international recognition (the film received an Oscar nomination for Best Foreign Film). His unprecedented success – reproduced on a smaller scale by Jésus de Montréal (Jesus of Montreal), three years later – set the pace for Yves Simoneau (Pouvoir intime – Intimate Power), Jean-Claude Lauzon (a rising star of Quebec cinema, who died after having produced Un zoo la nuit (Night Zoo) and Léolo) and Léa Pool (who became the most well-known Quebec filmmaker worldwide, largely due to La Femme de l’hôtel (A Woman in Transit), Anne Trister and Emporte-moi (Set Me Free)). The fallout from the defeat of the “Yes” vote in the first referendum lead to indifference regarding questions of national identity. One filmmaker, however, bucked this trend: Pierre Falardeau, himself the very embodiment of political cinema of the time, revisited both the October Crisis of 1970 (Octobre), and the Rebellions of 1837 (15 février 1839), using the same cutting satire through his character Elvis Gratton.

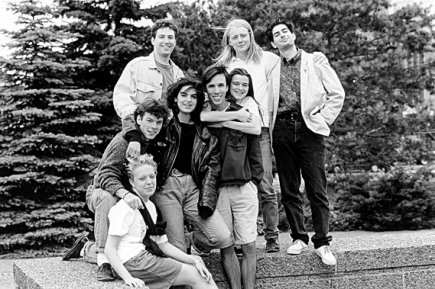

The TV series “La course destination-monde” 1990-91

Yet his films stayed off the radar at a time when a new generation was emerging via “La course destination-monde”, a TV series featuring young apprentice, globe-trotting filmmakers such as Philippe Falardeau (Congorama), Ricardo Trogi (Québec-Montréal), Yves Christian Fournier (Tout est parfait – Everything is Fine), Robin Aubert (À l’origine d’un cri) and Denis Villeneuve (Un 32 août sur terre – 32nd Day of August on Earth). This new generation slowly made its mark on Quebec cinema: a generation of talented stylists, fully versed in the aesthetics of advertising and music videos, and who leisurely pondered on all the mistakes made by dissatisfied thirty-somethings. Women’s cinema, motivated by a deep desire to break down prejudices, continued to expand as much in the fiction as the documentary genre, under the leadership of directors such as Paule Baillargeon (Le Sexe des étoiles – The Sex of the Stars), Micheline Lanctôt (Sonatine) and Catherine Martin (Les Dames du 9e).

Trailer for The Decline of the American Empire by Denys Arcand

Extract from Elvis Gratton by Pierre Falardeau

First sequence of Sonatine by Michèle Lanctôt

During the 1990s, this emphasis on form and originality inspired once more the films of André Turpin (Zigrail), Robert Lepage (Le Confessionnal – The Confessional), Manon Briand (2 secondes), Charles Binamé (Eldorado) and François Girard (Thirty-Two Short Films About Glenn Gould). Yet a new breed of films emerged, one somewhere between the heritage of Direct Cinema and the beginnings of low budget films, which would later infect the film industry with their boldness and urgent need to create: Robert Morin from Requiem pour un beau sans cœur (Requiem for a Handsome Bastard) through to Yes Sir! Madame…, presented a way of both filming and viewing that was as unique as it was striking. However, despite these undeniable artistic successes, it was commercial cinema, more specifically popular comedies, in the form of series such as Cruising Bar, Les Boys (The Boys) and C’t’à ton tour, Laura Cadieux (It’s Your Turn, Laura) that were most prosperous.

Trailer for The Confessionnal directed by Robert Lepage

Extract from Requiem for a Handsome Bastard directed by Robert Morin

Although Quebec’s cinematic identity had been fully asserted (in 1999, the first Jutra Award ceremony took place, affirming its uniqueness in a national context), the quest for revenue became even more of a priority in 2001, when Telefilm Canada implemented the policy of “performance envelopes”, thereby automatically awarding the majority of its funds to film producers who had already experienced the greatest successes at the box office. This situation did not, however, abate the emergence of several atypical works that periodically displayed the irrepressible diversity of Quebec cinema. The following list is by no means exhaustive: Les Invasions Barbares (The Barbarian Invasions) which followed Déclin (The Decline), was the biggest success of Denys Arcand’s career; La Grande Séduction (Seducing Doctor Lewis) by Jean-François Pouliot, remains to this day, the only mainstream Quebec comedy to have enjoyed international success; Gaz Bar Blues, the second feature film by Louis Bélanger, which casts a tender glance on a bygone Quebec that had all but disappeared; La Neuvaine (The Novena) by Bernard Émond was the first installment of a trilogy that illustrated theological virtues with unique thoroughness and an incomparable way of laying them bare; À l’ouest de Pluton (West of Pluto) by Henry Bernadet and Myriam Verreault presented a bittersweet portrait of contemporary adolescence and J’ai tué ma mère (I Killed My Mother) and Les Amours Imaginaires (Heartbeats) uncovered the talents of Xavier Dolan, who captured imaginations in both Quebec and France. In addition, C.R.A.Z.Y. by Jean-Marc Vallée and Incendies by Denis Villeneuve, both enjoyed runaway success on both sides of the Atlantic.

Trailer for West of Pluto directed by Henry Bernadet and Myriam Verreault

Extract from Heartbeats directed by Xavier Dolan

Trailer for Incendies directed by Denis Villeneuve

Yet despite the exceptions outlined above, Quebec cinema is still, to this day, torn between two conflicting poles. On the one side, the supposedly commercial productions (which are in fact financed by the State), revisit the conventions of supremely digestible and inconsequential cinema. On the other, independent film (often filmed in less than ideal circumstances), is shunned by its own audience, yet revered on an international level (films by Denis Côté at Locarno, Rafaël Ouellet at Karlovy Vary and Stéphane Lafleur at Berlin, as well as newcomers like Anne Émond, Guy Édoin and Sébastien Pilote). Marginal on its own soil, Quebec cinema, which remains steadfastly the reserve of film enthusiasts, is morphing into confused poetry, lined with traces of bittersweet humour, permeated by a sad downward force which reflects the state of Quebec cinema of today. A cinema which is losing its sense of self: in search of itself and unsure. A film industry in crisis, yet one which is ardently contemplating, with passion and integrity, the ways in which Quebec cinema can solve its own problems, by itself.

Trailer for Curling directed by Denis Côté

Trailer for The Salesman directed by Sébastien Pilote

> DOWNLOAD THIS ARTICLE AS A PDF

* Helen Faradji is a writer and film critic

The Festival de Cannes would like to thank all of the authors for contributing to the website for free.