ARGENTINIAN CINEMA

BY PAULO PARANAGUA*

Gaucho Nobility, 1915

Given the lack of an effective national film archive, it is thanks to the Buenos Aires City Museum that we are today familiar with Argentinian silent films. The Last Indian Attack (Alcides Greca, 1918), produced in Rosario, illustrates Sarmiento’s classic dilemma between urban civilisation and the barbarism of indigenous provinces with a curious blend of authenticity and artfulness. The same issue was treated in a more compassionate and conventional way in La Quena de la Muerte (Nelo Cosimi, 1928).

The Last Indian Attack (Alcides Greca, 1918)

During the silent era, screenings on calle Corrientes, the Broadway of Buenos Aires, were accompanied by “Latin American orchestras” playing tangoes. Max Glucksmann, a cinema owner, distributor and producer of new musical varieties, was also the first to publish music scores at a time when Argentinian music was becoming an export product.

During the silent era, screenings on calle Corrientes, the Broadway of Buenos Aires, were accompanied by “Latin American orchestras” playing tangoes. Max Glucksmann, a cinema owner, distributor and producer of new musical varieties, was also the first to publish music scores at a time when Argentinian music was becoming an export product.

In a way, the talkies can be seen to have promoted the links between tango and cinema. The director, José Agustin Ferreyra, whose career began in 1915, drew inspiration from the melodramatic atmosphere of popular songs and made a genuine star of Libertad Lamarque. Paramount quickly caught on to the potential of tango and signed a contract with its foremost exponent, Carlos Gardel, who was a living legend until his accidental death in 1935.

Argentinian producers continued to exploit the same vein to saturation point, alternating between tear-jerking melodramas and populist comedies. One particularly outstanding actress from those days still lingers in people’s memories: Nini Marshall, to whom Alfredo Arias paid a worthy tribute.

|

|

| Libertad Lamarque | Nini Marshall |

On the eve of World War II, major studios mushroomed in the suburbs of Buenos Aires: Lumiton, Argentina Sono Film and Estudios San Miguel, where Spanish Republican refugees found shelter with Miguel Machinandiarena, a boss of Basque descent. The Ghost Lady (Luis Saslavsky, 1945), for example, was a gorgeous Spanish version of Carnival in Flanders, featuring dialogues by Calderon de la Barca that were reworked by the poet Rafael Alberti.

The Ghost Lady (Luis Saslavsky, 1945)

While Argentina dominated Spanish-language productions, the United States backed its principal competitor, Mexico, for political reasons. In fact, the military who seized power in 1943 remained obligingly neutral towards the Germans, who were present in significant numbers in Argentina.

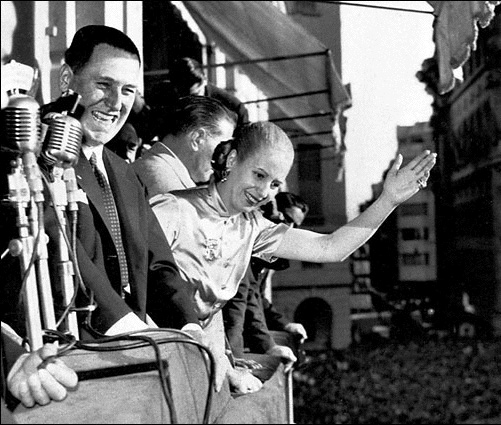

During the reign of General Juan Domingo Peron (1945-1955), his wife, the starlet Evita Peron, drew up a blacklist of artists who were forbidden to appear on screen or on the airwaves. Lamarque, Marshall and many others went into exile, strengthening their Mexican rivals. Peronist control focused on current affairs, but fear ensured that Argentinian productions remained mired in hoary clichés.

During the reign of General Juan Domingo Peron (1945-1955), his wife, the starlet Evita Peron, drew up a blacklist of artists who were forbidden to appear on screen or on the airwaves. Lamarque, Marshall and many others went into exile, strengthening their Mexican rivals. Peronist control focused on current affairs, but fear ensured that Argentinian productions remained mired in hoary clichés.

Modernity chomped at the bit in post-war cinema clubs and eventually flourished in Argentina after the fall of Peron, encouraged by the creation of a National Institute of Filmmaking in 1957. The figurehead for the transition between major studios and art-house films was Leopoldo Torre Nilsson, son of director Leopoldo Torres Rios, whose approach was distinctly realist.

The duo formed by Torre Nilsson and his novelist wife Beatriz Guido led to a series of oppressive works characterised by an expressionist, almost baroque, artistic vision: the trilogy, End of Innocence (1957) – The Fall (1959) – The Hand in the Trap (1961) gave the pair a place among the top ten most important living filmmakers according to critics in the English-speaking world.

La Casa del angel (1957) directed by Leopoldo Torres Rios

Throughout his prolific and irregular career, Torre Nilsson made use of crude neorealism (The Kidnapper, 1958), attacked political blockages (The Party is Over, 1960) and adopted the new generation’s freedom of expression (The Terrace, 1963), which he supported in the face of censorship and the over-cautiousness of more traditional producers.

Throughout his prolific and irregular career, Torre Nilsson made use of crude neorealism (The Kidnapper, 1958), attacked political blockages (The Party is Over, 1960) and adopted the new generation’s freedom of expression (The Terrace, 1963), which he supported in the face of censorship and the over-cautiousness of more traditional producers.

The “60s generation” or “Nuevo Cine” was a vague and diverse grouping that included, amongst others, David José Kohon, Leonardo Favio, Lautaro Murua, Manuel Antin and Fernando Birri, who were more or less divided between social angst, intimism and literary influences. However, even before it could reach its apogee, the movement faltered on account of the new restrictions imposed following the 1966 coup.

The “60s generation” or “Nuevo Cine” was a vague and diverse grouping that included, amongst others, David José Kohon, Leonardo Favio, Lautaro Murua, Manuel Antin and Fernando Birri, who were more or less divided between social angst, intimism and literary influences. However, even before it could reach its apogee, the movement faltered on account of the new restrictions imposed following the 1966 coup.

Under pressure, cinema found itself divided between a militant radical tendency, symbolised by the documentary, The Hour of the Furnaces by Fernando Solanas and Octavio Getino (1968), and allegory, a magnificent example of which is Invasion by Hugo Santiago (1969), based on a screenplay by Jorge Luis Borges and Adolfo Bioy Casares.

The Hour of the Furnaces directed by Fernando Solanas and Octavio Getino (1968)

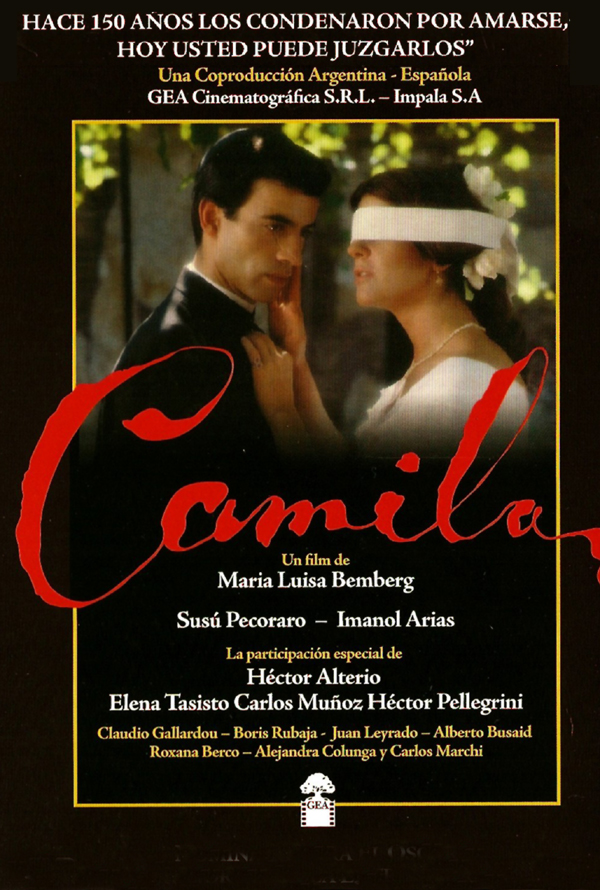

The democratic spring of 1973 paved the way for a greater range of expression, but this was short-lived as the putsch of 1976 plunged Argentina into a gulf of terror. This period also saw the rise of the directors Adolfo Aristarain (Time for Revenge, 1981) and Maria Luisa Bemberg (Camila, 1984).

The democratic spring of 1973 paved the way for a greater range of expression, but this was short-lived as the putsch of 1976 plunged Argentina into a gulf of terror. This period also saw the rise of the directors Adolfo Aristarain (Time for Revenge, 1981) and Maria Luisa Bemberg (Camila, 1984).

The renaissance of cinema under democracy, following a chaotic transition that was hardly auspicious for production, was nothing short of miraculous. Manuel Antin contributed to this revival in two ways: firstly, through his pluralist management of the National Institute of Filmmaking after democracy was restored in 1983, and secondly, by creating the Cinema University (known as the FUC) in 1991, which marked the beginning of a real explosion in film studies in Buenos Aires.

Now a bubbling metropolis once again, the capital’s festival of independent cinema has stolen top billing from the international Mar del Plata Festival, more prone to institutional vagaries. Buenos Aires is without doubt the city with the greatest number of film students per inhabitant in the world!

This desire for redemption through image gave birth to a new Argentinian cinema at the turn of the century. The country had never seen such a profusion of vocations or such a variety of movements. Local and international audiences made a success of The Secret in their Eyes (2009) directed by Juan José Campanella, a regular Argentinian contributor to the world of American television series, who won a timely Oscar.

Cinema-lovers will have retained the names of Pablo Trapero (Crane World, 1999), Lucrecia Martel (The Swamp, 2001) and Martin Rejtman (Silvia Prieto, 1998) from their very first films. Those undaunted by a more ascetic approach would no doubt also add Lisandro Alonso (Freedom, 2001) and Israel Adrian Caetano (Bolivia, 2001) to the list.

Children of militants who disappeared or died under the military dictatorship have embraced subjective documentary narrated in the first person to express their grief and duty to remember. In this, they have refused to be subservient to previous generations, as demonstrated by The Blonds (Albertina Carri, 2003) and M (Nicolas Prividera, 2007), preceded by an example of unabashed subjectivity, La T.V. y yo (Andrés Di Tella, 2002).

Argentinians are not short of hope or even faith in the future of their cinema. Long may it last!

Argentina at Cannes

Elsa Daniel, the muse of Leopoldo Torre Nilsson, made a lasting impression at Cannes back in 1959 during the presentation of The Fall. The director himself was awarded a prize by the FIPRESCI in 1961 for The Hand in the Trap. The international reputation of Torre Nilsson owes much to English and French criticism. Marcel Oms wrote a first monograph about him in 1962 in the Premier Plan collection directed by Bernard Chardère, a Cannes regular.

Elsa Daniel, the muse of Leopoldo Torre Nilsson, made a lasting impression at Cannes back in 1959 during the presentation of The Fall. The director himself was awarded a prize by the FIPRESCI in 1961 for The Hand in the Trap. The international reputation of Torre Nilsson owes much to English and French criticism. Marcel Oms wrote a first monograph about him in 1962 in the Premier Plan collection directed by Bernard Chardère, a Cannes regular.

Festival-goers had the privilege of watching a film by Manuel Antin, The Venerable Ones (1962), which tackles the fascistic tendencies still prevalent in Buenos Aires. As such, this ill-fated film remains unreleased in its own country.

At the 1985 festival, Norma Aleandro, an important figurehead of Argentinian cinema, won the prize for Best Female Actor (jointly with Cher) for Luis Puenzo’s The Official Story, which was also recognised by the Ecumenical Jury before scooping the Oscar for Best Foreign Film the following year.

The Official Story directed by Luis Puenzo

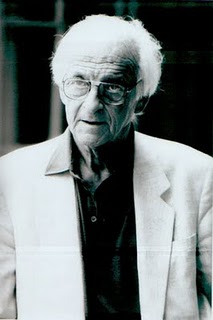

Strengthened by years of exile in France and a successful transition to fiction, Fernando Solanas won the Award for Best Director in 1988 with The South, an entirely musical film about a past that refuses to go away and the impossibility of turning back the clock. Returning to the Croisette four years later with The Journey, Solanas won the Ecumenical Prize and the Superior Technical Commission award.

The South directed by Fernando Solanas

Un Certain Regard, Critics’ Week and the Directors’ Fortnight have now taken up the baton for the new generation of Argentinian filmmakers.

> DOWNLOAD THE ARTICLE AS A PDF

* Paulo Paranagua is a journalist and film historian.

The Festival de Cannes would like to thank the authors for contributing to the website for free.