LETTER FROM THE BRITISH PRODUCER, COLIN MACCABE

In the first week of May 1985 I was appointed Head of Production at the British Film Institute (BFI). It was not just a new job, but a new career and I was keen to meet everybody in the business. I rang Channel 4 – “They’re all in Cannes next week”, I rang British Screen “I’m afraid we’re all going to be in Cannes next week”. I rang the Trades, I rang the professional associations. The same response. On the well-known principle that if the mountain will not come to Mohammed then Mohammed will go the mountain, my second day in my new job had me asking my assistant to book me a flight and a hotel in Cannes. For the first lesson of the film business is that everybody is in Cannes. Not just all the suits in the British film industry, but the Hollywood majors, the small European distributors with whom I was to do business for the next five years, and filmmakers from Mali and Thailand, from Brazil and Mexico. Nowhere else in the world is every level of the film business gathered together. And while the glitz and the glamour, the money and the sleaze are all in evidence; it still remains the case that the only real currency in Cannes is film. In the end, all the journalists and festival managers, all the producers and financiers are there for one reason, for that moment when a new film casts a fresh angle on the world where illumination is provided by sound and image.

In the first week of May 1985 I was appointed Head of Production at the British Film Institute (BFI). It was not just a new job, but a new career and I was keen to meet everybody in the business. I rang Channel 4 – “They’re all in Cannes next week”, I rang British Screen “I’m afraid we’re all going to be in Cannes next week”. I rang the Trades, I rang the professional associations. The same response. On the well-known principle that if the mountain will not come to Mohammed then Mohammed will go the mountain, my second day in my new job had me asking my assistant to book me a flight and a hotel in Cannes. For the first lesson of the film business is that everybody is in Cannes. Not just all the suits in the British film industry, but the Hollywood majors, the small European distributors with whom I was to do business for the next five years, and filmmakers from Mali and Thailand, from Brazil and Mexico. Nowhere else in the world is every level of the film business gathered together. And while the glitz and the glamour, the money and the sleaze are all in evidence; it still remains the case that the only real currency in Cannes is film. In the end, all the journalists and festival managers, all the producers and financiers are there for one reason, for that moment when a new film casts a fresh angle on the world where illumination is provided by sound and image.

|

|

It was what the French call a “coup de foudre”. A rather prolonged one. It struck first as I lunched on the beach  where Tony Kirkhope of The Other Cinema and Andi Engel of Artificial Eye taught me more lessons about cinema through their jokes than I had learned in a thousand lectures. It struck again that first night as I lurched from party to party, meeting producers and distributors from every corner of the globe, all of them with projects – at least by the third drink – which sounded as though they would not simply herald a revolution in cinema, but probably in the world as well. It struck for a third time the next morning as, for the first time, I sat in the Grand Palais at 8.30 in the morning before the largest screen I had ever seen and watched, through a paint bubbling hangover, a newly struck print perfectly projected with perfect sound. The film was Peter Bogdanovich’s Mask and, if it was not a great film, Cher had never looked more beautiful.

where Tony Kirkhope of The Other Cinema and Andi Engel of Artificial Eye taught me more lessons about cinema through their jokes than I had learned in a thousand lectures. It struck again that first night as I lurched from party to party, meeting producers and distributors from every corner of the globe, all of them with projects – at least by the third drink – which sounded as though they would not simply herald a revolution in cinema, but probably in the world as well. It struck for a third time the next morning as, for the first time, I sat in the Grand Palais at 8.30 in the morning before the largest screen I had ever seen and watched, through a paint bubbling hangover, a newly struck print perfectly projected with perfect sound. The film was Peter Bogdanovich’s Mask and, if it was not a great film, Cher had never looked more beautiful.

All great loves, if they are to endure, need a rational basis to support the initial mad attraction and I worked out pretty quickly that, not only did I want to go to Cannes every year, but my job was to make sure that I had a hit there. The British Film Institute Production Board funded small films that could not, because of their subject matter or their formal innovation, find commercial backing. But my job didn’t finish with the delivery of an answer print. We were determined that these small films would reach their widest possible audience. Although they were many festivals which could help in this, there was only one that could take a small film and launch it into worldwide distribution. I had seen this happen in 1985 when Spike Lee’s She’s Gotta Have it” exploded out of the festival. From May 1985, I had only one ambition – to take a film to Cannes and have it acclaimed by the only audience that could take a tiny film onto the world stage.

Still Lives Distant Voices directed by Terence Davies

One of the first films I produced was Terence Davies’s Distant Voices and when I sat down and watched the final cut in November 1985, I knew I had my Cannes film. The only problem was that it was only 45 minutes long. There were many voices urging immediate release, for the film would undoubtedly be a -Affiche.jpg) hit on the festival circuit and Andi Engel went so far as to offer the best screen in London, The Lumiere, where he would exhibit it as a feature. But I couldn’t get Cannes out of my mind. I knew that Terence had a companion piece, Still Lives, and, although he still had to write the script and the money was unraised, the thought of Cannes made me determined to take the risk and aim for a full length feature. It took 2 more years for the second half to be written financed and shot, but when in 1988 the audience in the old Palais burst into what seemed never-ending applause, I knew the risk had paid off. In fact the applause lasted about 15 minutes, but in those 15 minutes, buyers from almost every country in the world had decided they wanted to acquire the film. A film recording the ordinary lives of a working class family in pre-consumer Liverpool, without real narrative incident or spectacular effects, secured a world audience through its selection and reception at Cannes. Two years later Isaac Julien’s Young Soul Rebels achieved similar success and I was, at forty, to conclude the last night of my adolescence when at 9 o’clock in the morning, and without having slept, I concluded its sale to Gerard Vaugeois and Film de l’Atalante over a glass of pastis. The next year bought an even more signal honour when Terence Davies’s The Long Day Closes, in my opinion his very finest film, was selected for the main competition and I was able to make the montée des marches.

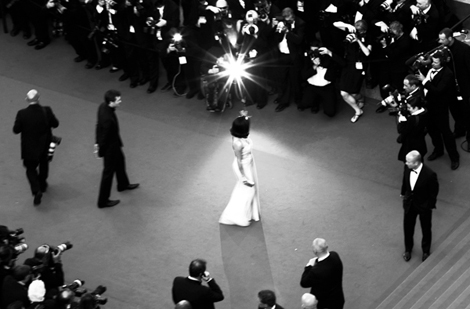

hit on the festival circuit and Andi Engel went so far as to offer the best screen in London, The Lumiere, where he would exhibit it as a feature. But I couldn’t get Cannes out of my mind. I knew that Terence had a companion piece, Still Lives, and, although he still had to write the script and the money was unraised, the thought of Cannes made me determined to take the risk and aim for a full length feature. It took 2 more years for the second half to be written financed and shot, but when in 1988 the audience in the old Palais burst into what seemed never-ending applause, I knew the risk had paid off. In fact the applause lasted about 15 minutes, but in those 15 minutes, buyers from almost every country in the world had decided they wanted to acquire the film. A film recording the ordinary lives of a working class family in pre-consumer Liverpool, without real narrative incident or spectacular effects, secured a world audience through its selection and reception at Cannes. Two years later Isaac Julien’s Young Soul Rebels achieved similar success and I was, at forty, to conclude the last night of my adolescence when at 9 o’clock in the morning, and without having slept, I concluded its sale to Gerard Vaugeois and Film de l’Atalante over a glass of pastis. The next year bought an even more signal honour when Terence Davies’s The Long Day Closes, in my opinion his very finest film, was selected for the main competition and I was able to make the montée des marches.

The Long Day Closes (1992) directed by Terence Davies – final scene

But Cannes is not only about the showing of completed films, it is also about the raising of money for projects as yet merely figments of the imagination. Until 1993, my experience of production was limited to raising money from small arthouse distributors. That year, however, I came to Cannes with slightly bigger fish to fry, but unable to find a frying pan large enough. Channel 4 had asked me to find a project to celebrate the centenary of cinema and I had persuaded Stephen Frears to try his hand at a history of British cinema.

Extract from the documentary by Stephen Frears about the history of British cinema

Frears in turn had pitched the project to Martin Scorsese who had long wanted to make his own history of American cinema. Perhaps those two films should have been enough, but the ambition we had formed at the BFI was to make sixteen such films that would celebrate the real global range of cinema, not limited to the Anglophone or the developed world. The idea was to organize a huge “club” production in which each country paid for its own film and in exchange for ceding all its international rights acquired the rights for all the other films in its own territory. The only original idea of the series was to ask great directors to make a film about the history of film in their own country or region. Fiction or documentary, narrowly focused or attempting a long overview, we asked only that the director make a personal film. The enthusiasm with which our request was greeted was phenomenal – Oshima in Japan, Nelson Pereira dos Santos in Latin America, George Miller in Australia – in every country, our director of choice said yes.

The only snag was that we had nothing to offer to get the club production going. Channel 4 would pay for both Scorsese and Frears but then they would, not unreasonably, take all rights. I had to find at least $500,000 of the Scorsese budget if I was to have anything to offer to other countries. By May 1993, I was in despair. I had tried all my contacts as a producer and had got nowhere. That year Jeremy Thomas was made Chair of the British Film Institute and it was with some trepidation that l went to knock on his door in the Carlton. Jeremy is now one of my closest friends, but at that time, I just knew him as the most legendary producer of my generation, a man who, entirely independently, backed his own taste and succeeded. Jeremy has a slight squint, which makes it difficult to know if he is giving you his full attention, and he is also a man with the quickest mind that I have ever met – he always seems to be doing four things at once. As I sat in his suite, trying to encapsulate the ambition of the series and to say why it was so important for the British Film Institute to make a series that really celebrated the full range of world cinema, Jeremy was serving drinks to guests, taking telephone calls, reading the trades and rolling cigarettes. I sputtered to a stop, not at all sure that Jeremy had heard, let alone, understood, a word. “Are you free now?” he said. “Yes” I gulped. “Then follow me”. For the next 30 minutes, we raced up and down the Croisette diving into an office here and a hotel there. It could only happen at Cannes, but at the end of the race I had a cheque for $500,000 dollars and all 16 films became possible.

went to knock on his door in the Carlton. Jeremy is now one of my closest friends, but at that time, I just knew him as the most legendary producer of my generation, a man who, entirely independently, backed his own taste and succeeded. Jeremy has a slight squint, which makes it difficult to know if he is giving you his full attention, and he is also a man with the quickest mind that I have ever met – he always seems to be doing four things at once. As I sat in his suite, trying to encapsulate the ambition of the series and to say why it was so important for the British Film Institute to make a series that really celebrated the full range of world cinema, Jeremy was serving drinks to guests, taking telephone calls, reading the trades and rolling cigarettes. I sputtered to a stop, not at all sure that Jeremy had heard, let alone, understood, a word. “Are you free now?” he said. “Yes” I gulped. “Then follow me”. For the next 30 minutes, we raced up and down the Croisette diving into an office here and a hotel there. It could only happen at Cannes, but at the end of the race I had a cheque for $500,000 dollars and all 16 films became possible.

Stephen Frears

The end of the story was even better because who knows if the 16 films would have reached a global audience had it not been for Gilles Jacob and Cannes. In early January 1995, Jacob phoned me to tell me that he had heard of the series and would be interested in looking at the films that were finished. Seven of them would be ready for May and Jacob took all seven, placing them in a special section. The week during which I showed a film a night at Cannes is still one of my most cherished memories. The festival made me feel as though I had really made a contribution to the celebration of cinema. The coup de foudre had, miraculously, become a marriage.

> DOWNLOAD A PDF OF THE ARTICLE

The Festival de Cannes would like to thank all the authors for contributing for free.