1951–1999: A brief history of short films. Interview with Jacques Kermabon

As Editor-in-Chief of Bref, published by the Short Film Agency, and author of Une encyclopédie du court métrage français with Jacky Evrard in 2003, Kermabon prepared the programme for the seven shorts presented at Cannes Classics with Christian Jeune, director of the Film Department. We asked Kermabon– a member of the short film selection committee at Cannes – about A brief history of short films.

What gave you the idea of presenting a programme of short films as part of Cannes Classics?

This part of the Festival showcases the finest moments in motion picture history, in recently restored form. So it seemed obvious this should also include short films, a part of the film world that boasts truly remarkable works, some of which have been digitally restored.

The 70th anniversary of the Festival de Cannes seemed an excellent opportunity to offer the festival-goers a selection of films that have won acclaim down the years.

What were your selection criteria?

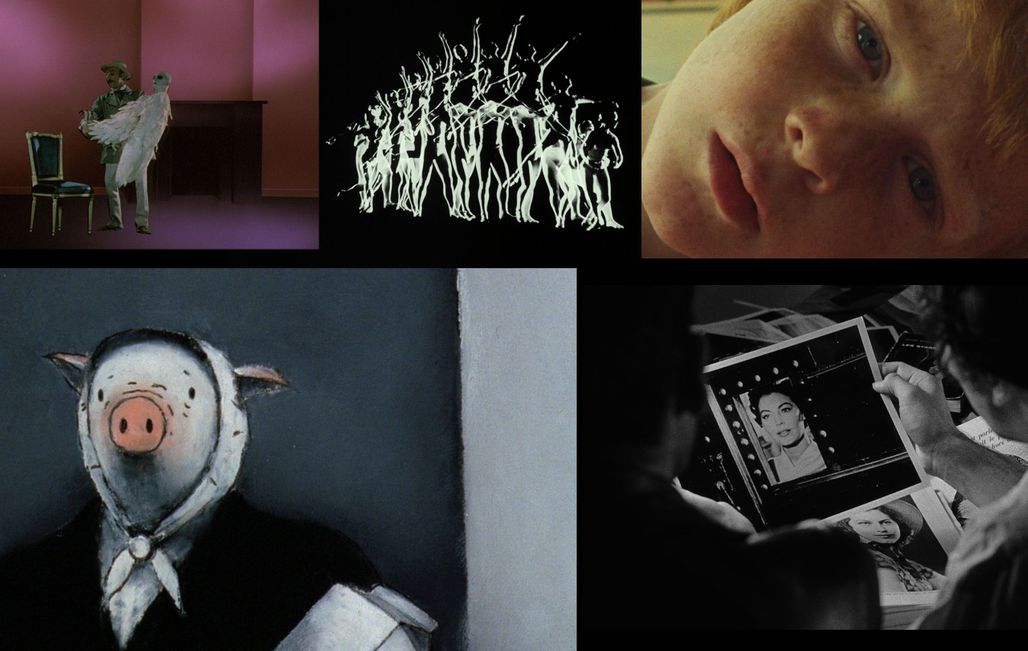

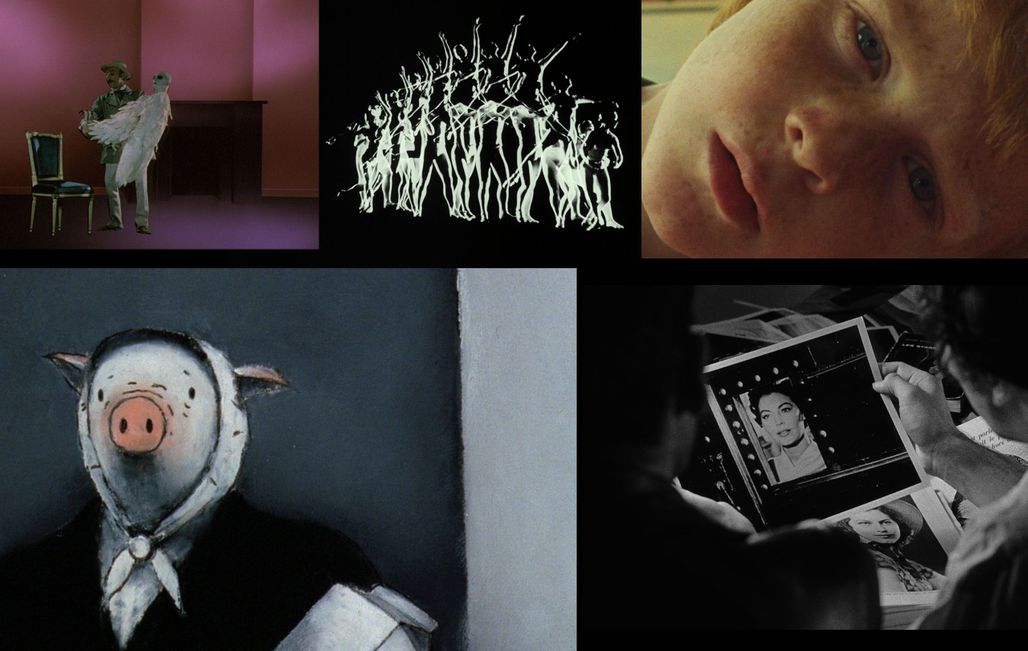

Our process was driven primarily by a need for eclecticism, in order to reflect a wide diversity of countries, years and genres. Alongside fiction, documentaries are represented – in a contemplative, experimental sense – by Bert Haanstra’s Miroirs de Hollande (1951), and from a more traditional point of view by the magnificent La Seine a rencontré Paris, by Joris Ivens (1958), based on a text by Jacques Prévert. Harpya, by Raoul Servais (1979), and When the Day Breaks, d’Amanda Forbis and Wendy Tilby (1999), embody two aspects of animation films.

These films all obtained the highest award at the Festival, except for Norman McLaren’s Pas de deux, which was selected in the year the event was cancelled. This souvenir from 1968 is also a nod to the work of the greatest artists of the 20th century.

What is interesting about this particular format? What does it offer that feature films don’t?

There’s no difference in essence between shorts and features. Apart from the question of length, it’s mostly the economic conditions and the way in which they are presented that distinguish them.

At the same time, the spectrum of short films is less bound up with market laws and so enjoys greater diversity. Of course, there are fictional works based on formulae similar to those of features, but there are also works that are more akin to poems, outbursts of passion, essays, visual explorations, and so on.

Jane Campion, president of the Cinéfondation and Short Film Jury in 2013, said she saw short films as a necessary step along the way for any director before making features.

Campion’s Peel (1986) is an eloquent example of this. Similarly, Xavier Giannoli (Interview, 1998) had a few trial runs before making his first feature. These initial steps no doubt gave him greater confidence, and helped him explore his limits and try out a few experiments. And yet, Peel and Interview are far more than simple calling cards. The scope and ambition of their directors are perfectly in tune with the chosen duration and the truth of the story they tell.

But there’s nothing limiting about this way of approaching the production of shorts. Many of the directors in the programme presented in Cannes Classics have never made a feature and nothing suggests they want to do so in future. Their works illustrate other dimensions of the short form.