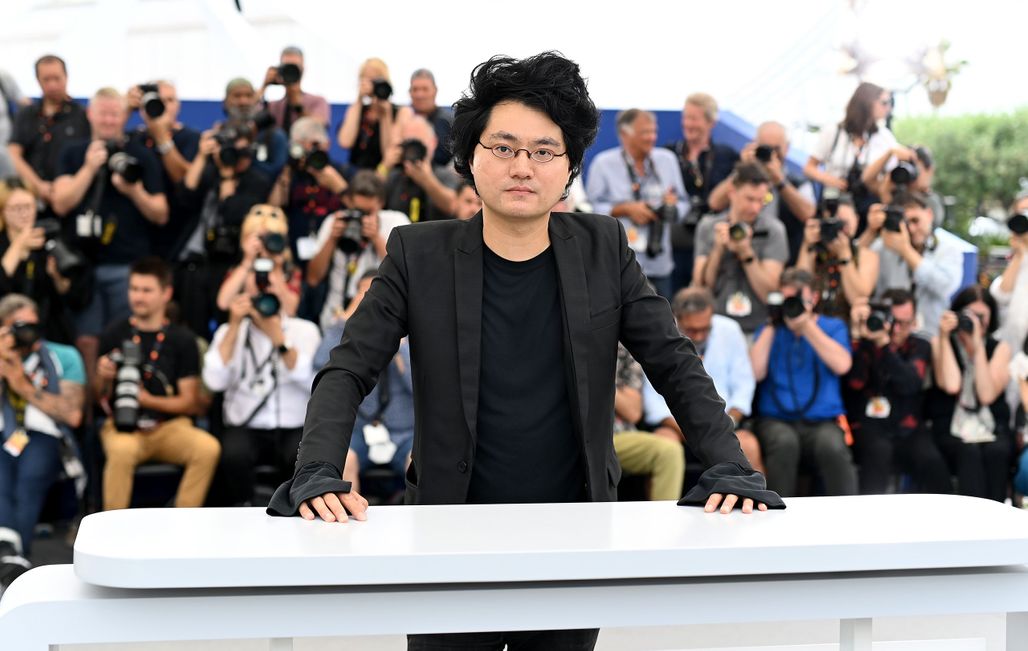

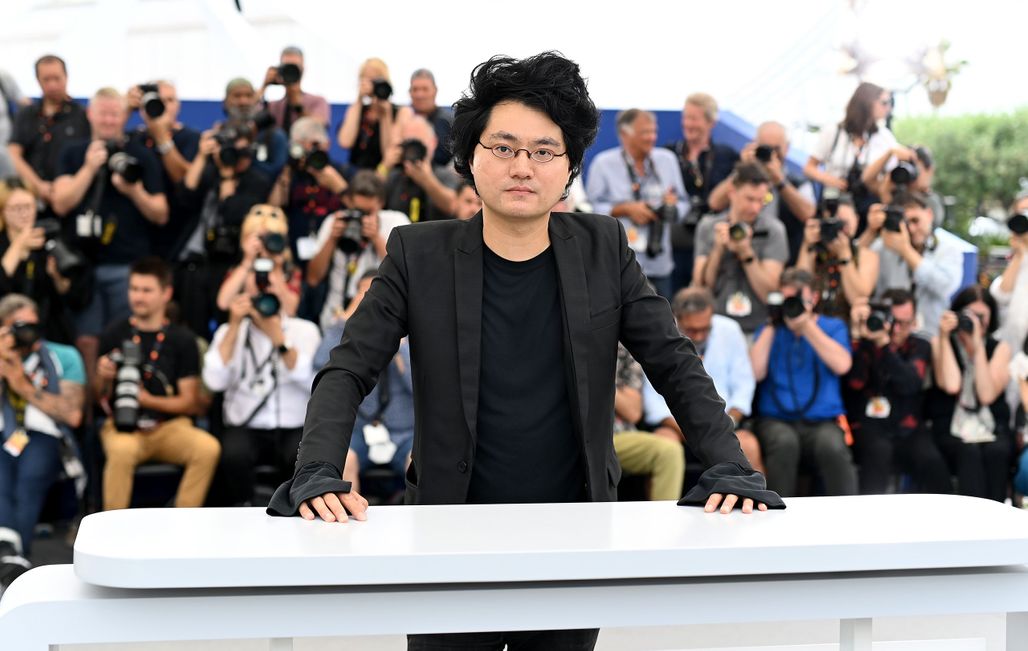

Encounter with Davy Chou, member of the Un Certain Regard Jury

There’s something vibrant about Davy Chou‘s films. The Franco-Cambodian director who made an impact in the Certain Regard section last year with Retour à Séoul (Return to Seoul), a film about Freddie’s quest for identity, returns this year as part of the Certain Regard Jury, presided over by John C. Reilly.

What has changed in your profession since the selection of “Return to Seoul” in the Certain Regard section?

I had already shown films at the Directors’ Fortnight and the Critics’ Week, but the Official Selection gave me a special spotlight, especially internationally. Before coming to the Festival, “Return to Seoul” had been pre-purchased by Sony Pictures Classics and Mubi. So all the attention was already on the film, and the press wanted to know how good it was. The combination of Certain Regard, these two acquisitions, and positive reviews has brought about quite a few changes in the past year. The film has been released in several foreign countries, and that’s a big change. Returning a year later in a position on the Jury, I didn’t expect it at all, and it’s an extremely privileged position.

And now that you’re here?

Being invited here is a true honour. The only strange thing, to be honest, is that I remain a filmmaker who hasn’t made many films, and I will be “judging” filmmakers who have the same experience as me, or even more. There are filmmakers showing their third film or who are older. And at the same time, it’s an opportunity for me to defend the cinema that I believe in and certain visions.

What does the cinema represent for you?

I mostly live in Cambodia, where there were no cinemas between the 1990s and around 2011. I interact with young people who didn’t have that habit at all when they were young, unlike me, because I was born and raised in France. We ask ourselves, “Will we lose this cinema experience?” And when I see that I’m surrounded by people who didn’t have that in their youth and how unique and rare that experience is, it would be extremely sad to lose it.

Which filmmakers inspire you?

My love of cinema has evolved with age. I grew up with New Hollywood. Then I became interested in the French New Wave. After that, I discovered modern cinema with In The Mood For Love in 2000, which brought a more radical and formal cinema, from Hou Hsiao-hsien and Jia Zhangke to Apichatpong Weerasethakul. But I also love American cinema, like Paul Thomas Anderson, James Gray, or Quentin Tarantino. All filmmakers who invent new forms inspire me, and that’s the most difficult thing to do today. I see it; everyone has their own influences.

“One of the challenges I face is coming after the history of cinema and finding room to invent a form.”

How do you free yourself from these models?

That’s a question that occupies me. If I’m a bit critical of my work, I would say that I can see in “Le Sommeil d’or” and “Diamond Island” a trace that is almost too literal of influences. I know why I did it. Because these are films that I shot in Cambodia, a country that has lost the memory of its cinema. More than that, it has been hindered in the development of its cinema due to the Khmer Rouge, which is the subject of my first film. So it made sense to draw from influences of modern Asian cinema in relation to shooting in a country that has somewhat lost its history of images. But in “Return to Seoul,” for example, which is a film that deals with identity, particularly cultural identity, I was

The theme of the past and roots is present in some of your films. What inspires you about this subject?

We make films with who we are. What I find funny in hindsight is that sometimes we attach ourselves to ideas for underlying reasons that push us to embrace our intuitions. Then, in the process of creation, we realize that these are very intimate and almost autobiographical things. When I was making “Return to Seoul,” I didn’t think it was a film that would tell my own story. I’m caught between two cultures, I knew absolutely nothing about Cambodia until I was 25, and now I spend more than 50% of my time there. Yes, these are themes that are dear to me. It’s even more than that: it’s me.

What are you currently working on?

I’m doing some writing. I’m waiting for the post-Cannes period. The fact that I get to see two, three, or even four films a day allows me to explore images from all over the world, from emerging or established filmmakers. Seeing these proposals, these forms, and all this variety as a filmmaker is extremely stimulating. Plus, we position ourselves as members of the Jury. It’s the perfect activity to close the chapter of this year following “Return to Seoul” and start the next film. This whirlwind of images for twelve days will be the key moment for me to transition into creating new forms.