A JOURNEY THROUGH AFRICAN CINEMA

BYJEAN-PIERRE GARCIA*

|

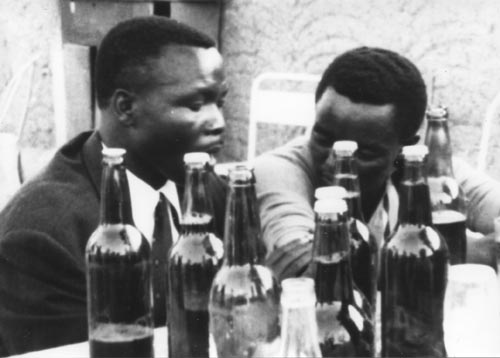

| Borom Sarret, Sembène Ousmane, 1963 |

The film that really marked the beginning of African cinema was Borom Sarret (1963) by Senegalese director Sembène Ousmane. Although Sudan’s Gadalla Gubara had been the first African on the continent to make a film with his documentary Song of Karthoum (1950), Sembène Ousmane remains the father figure by common consent. In tackling the story of a cart-driver subjected to the rules and regulations of the new regime, Borom Sarret sides with the poor of Dakar. This short film, which stirred consciousness and spoke out symbolically, led the way for future generations of filmmakers firmly focused on their own continent.

|

|

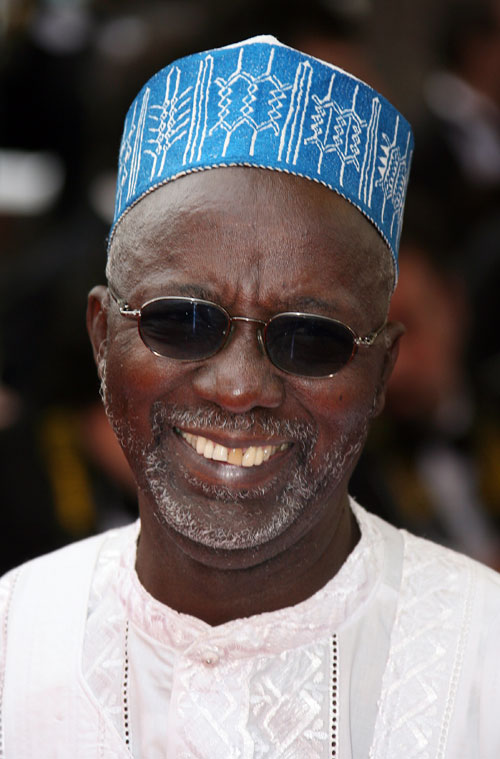

| Gadalla Gubara, 2007 © Nadja Korinth | Gadalla Gubara, Song of Khartoum, 1950 |

Filmmakers: (re)awakening consciousness

|

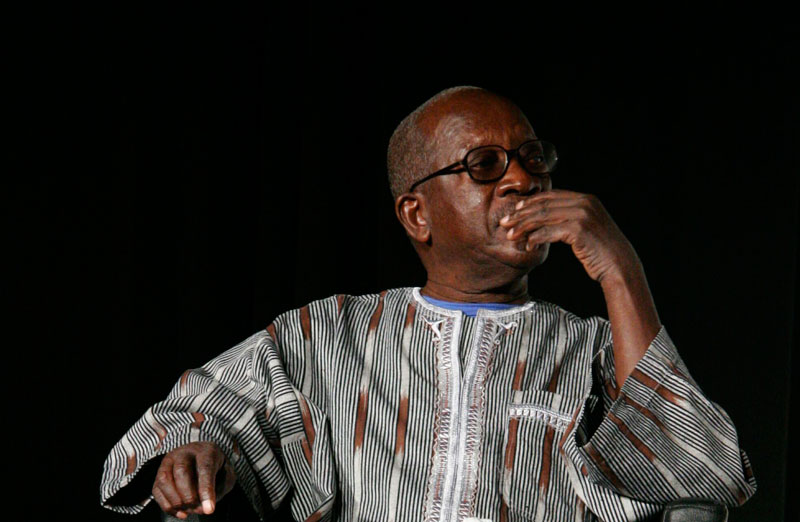

| Sembène Ousmane’s Cinema Masterclass, 2005 |

For the “father” of African cinema, the newly gained political independence only made sense if it was accompanied by a restoration of dignity, which had hitherto been suppressed by the weight of the administration and its reductive mechanisms (language, religion, education and the police). From the outset, cinema became the instrument of choice in this process of re-conquest: images were used to rebuild self-image, as well as the image of every population on the continent. In his cinema seminar at Cannes in 2005, Sembène Ousmane recalled: “I was gripped by a need to ‘discover’ Africa. Not just Senegal, but just about the entire continent… I became aware that I had to learn to make films if I really wanted to reach my people. A film can be seen and understood even by illiterate people – a book cannot speak to entire populations!” Sembène Ousmane laid the aesthetic foundations of his filmmaking (very close to Italian neo-realism) and set them in a pan-Africanist context. The initial equation was simple: independent Africa “needed” filmmakers who could (re-)awaken consciousness to counter colonial cinema, which had set out merely to entertain its audience, alienating them in the process.

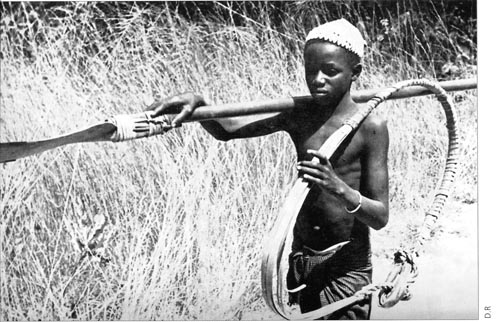

Around fifteen films made their mark over the course of this first decade (1964-1974). All dealt with either the colonial past and the liberation movements, or cultural assimilation and the problems of the newly independent states (corruption, bureaucracy, the shifting of wealth, etc.) The traumatic aftermath of the colonial past was addressed in Oumarou Ganda’s Cabascabo(1) (1968, Niger), Sarah Maldoror’s Monagambee (1968, Angola), Michael Raeburn’s Rhodesia Countdown (1969, Rhodesia), Sembène Ousmane’s Emitai (1971), and Nana Mahomo’s Last Grave at Dimbaza (1974, South Africa).

|

|

|

| Cabascabo, 1968 |

Emitaï, 1971 | Concerto For an Exile, 1968 |

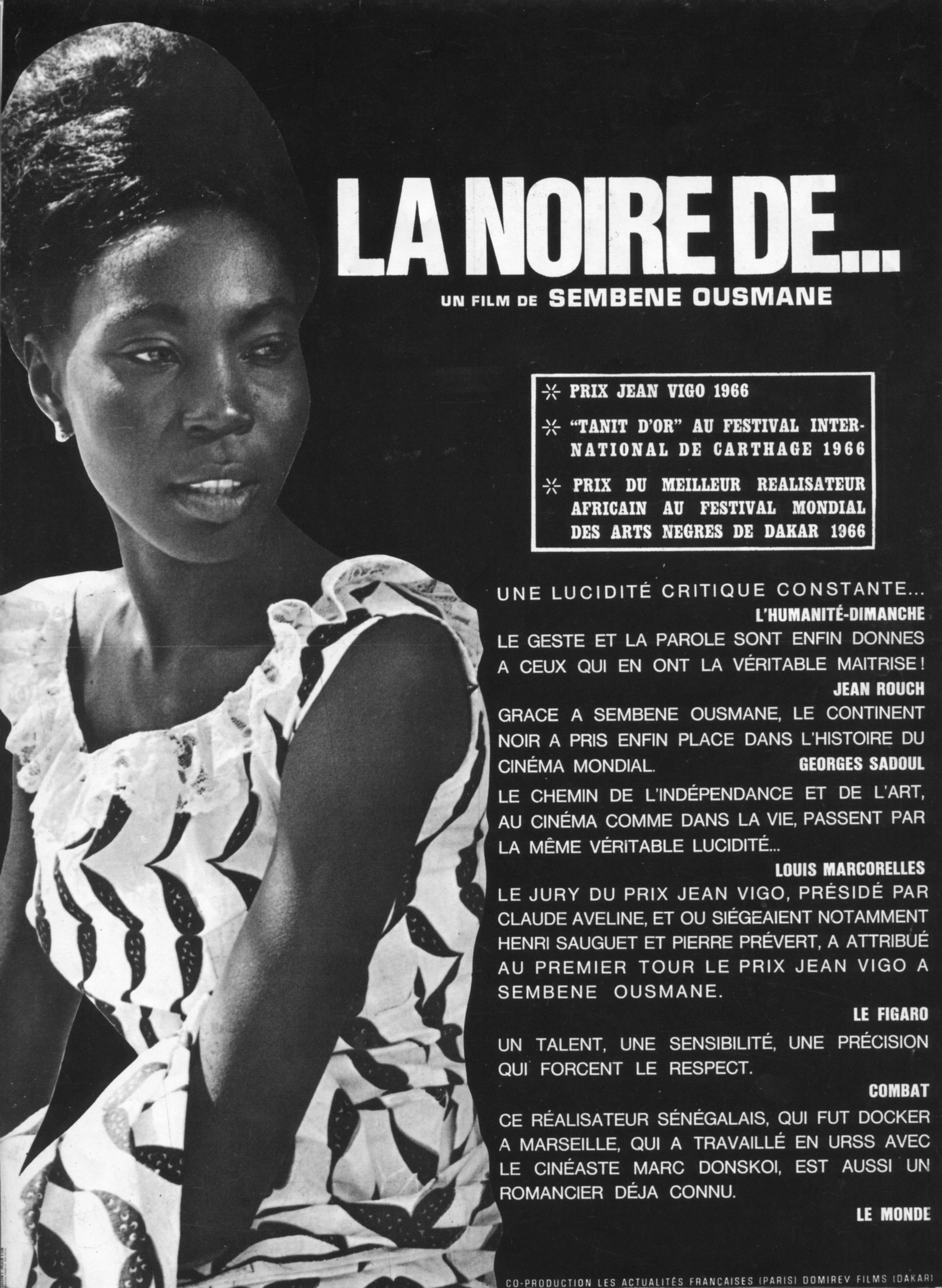

The films frequently focused on the suffocating links between the European and African capitals, as in Concerto For an Exile and Take Care, France by Désiré Écaré (1968 and 1970, Ivory Coast) or Djibril Diop-Mambéty’s Badou Boy (1970, Senegal). Other themes explored include the loss of identity through immigration, as in Sembène Ousmane’s Black Girl (1966), or the conflict with new regimes or corruption as in his The Money Order (1968) and Xala (1974).

|

|

| Black Girl, Sembène Ousmane, 1966 |

Reconstructing Africa’s own history; weaving its identity

The Africa that made its entry into the cinematic world in 1975 had thrown off its colonial shackles. Nine films were selected at Cannes between 1975 and 1985, all of which endeavoured to reflect African reality while examining the cultural roots of societies undergoing change. One image could serve as a common denominator for works as varied as N’Diangane by Mahama Johnson Traoré (1975, Senegal), Harvest: 3,000 Years by Haile Gerima (1976, Ethiopia), Ceddo by Sembène Ousmane (1977), Ababacar Samb-Makharam’s Jom (1981, Senegal) and Souleymane Cissé’s The Wind (Finyé, 1982, Mali): that of a pendulum constantly swinging between the present and the past. It is in this movement, with its focus on group identity (whether in cities or villages) in which individuals exist only in relation to a common destiny, that the films of this period can be contextualised. These films set out to recapture their country’s history: the stories of everyday men and women reflecting those of the earliest narratives and myths.

Jom, Ababacar Samb, 1981

|

| The Wind, Souleymane Cissé, 1982 |

Rather than praising the brave feats of one particular character, it is “the spirit of resistance” that Sembène commends in Emitai (1971) and Ceddo (1977), just as Ababacar Samb-Makharam celebrates a sense of honour (Jom) rather than singing a eulogy to one particular man of honour. The aim of these films is to bear witness, rather than present a hero in the Western sense of the term. This rather disconcerting (for Westerners) rule of thumb, coupled with the difficulty of classifying these films into production-distribution categories, explains the relative difficulty they encountered in winning over European audiences. This reduced key films in cinematographic history, such as Djibril Diop Mambéty’s Touki Bouki (1973) or The Wind (Finyé, 1982) to mere secondary status.

African cinema had not yet emerged from its ghetto, in the sense that it had not yet acquired or won international stature. It was entirely devoted to marking out its own cultural and human space, while its filmmakers staked out their territory. The challenge in the 1980s was to achieve recognition on a national and international scale.

Touki Bouki, Djibril Diop Mambéty, 1973

1987: Yeelen (Brightness)

|

|

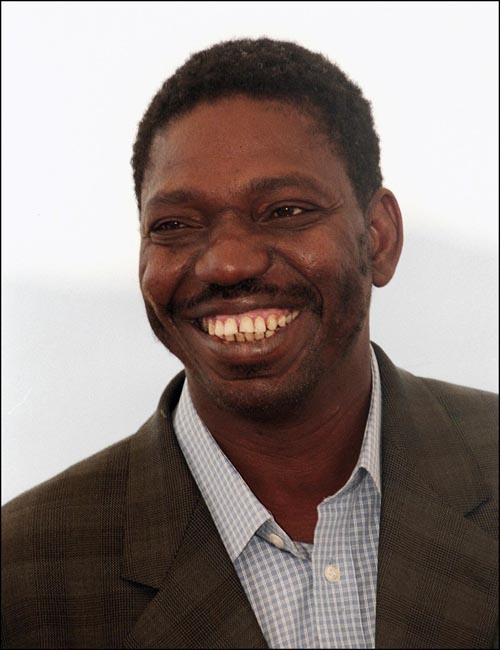

| Souleymane Cissé | Idrissa Ouedraogo |

The real turning point for African cinema occurred in 1987 with the selection of Yeelen (Brightness) by the Malian Souleymane Cissé for the official competition on the one hand, and of Yam Daabo (The Choice) by Burkina Faso’s Idrissa Ouedraogo for the Critics’ Week on the other. Yeelen was in fact the first Black African Film to compete at Cannes, and the film played its part to the full. The initiatory voyage undertaken by its main character setting out to master the forces surrounding him mirrors that of African cinema in the world of festivals – and Cannes in particular. The next steps were Raymond Rajaonarivelo’s Tabataba (1988, Madagascar) and Idrissa Ouedraogo’s Yaaba (1988, Burkina Faso), both of which featured in the Directors’ Fortnight. Then Tilaï (1990) by the prolific Ouedraogo, once again selected for the official competition.

Yeelen, Souleymane Cissé, 1987

Tilaï , Idrissa Ouedraogo, 1990

But then came the events of 1991, which certain journalists hungry for an exotic headline labelled the “Black Croisette”. For the first time, there were four African feature films at Cannes: Ta Dona by Adama Drabo (Mali), Sango Malo by Bassek Ba Kobhio (Cameroon), and Laada by Drissa Touré (Burkina Faso) were screened at Un Certain Regard, while Pierre Yaméogo’s Laafi (Burkina Faso) was selected for the Critics’ Week.

The decade turned out to be a prolific one: Hyenas by Djibril Diop Mambéty was entered for the international competition in 1992, as was a brilliant adaptation of Friedrich Dürrenmatt’s The Visit. Meanwhile, tiny Guinea-Bissau made its entry at Un Certain Regard with Flora Gomes’s Udju Azul di Yonta, along with October, by unknown Mauritanian filmmaker Abderrahmane Sissako.

|

|

|

|

Hyenas, 1992 |

Udju Azul di Yonta, 1992 |

October, 1993 |

Attitudes towards films made in sub-Saharan Africa have changed. The strength of the themes, the unique relationships not only to a film’s locale but also to its sound and music, and the staging ideas (imbued with a sophisticated bareness) developed by African directors have provided the answers sought by so many. Beyond the obvious themes, what was once considered disconcerting has come to be seen as a sign of vitality and evidence of a constantly renewed creative energy. The link to an oral tradition is expressed by symbolic, dramatic or amusing images that are as subtle as proverbs. When, in 1991, African cinema enjoyed its “merry month of May” as the late lamented Jacques Le Glou put it, it seemed as if African cinema had at last taken off. But such a view did not take Africa’s fragile economic situation into account, or the dependence of these filmmakers on funding from countries in the North. A closer look at African film production reveals that the number of films made each year is varied and cyclical. Everything depends on the support policies of European organisations and administrations, and their levels of funding. To take just the last two decades: there were peaks of production in the early and mid 1990s as a result of significant, regular and well-distributed support, before the machine seemed to grind to a halt.

Since then, a whole new set of directors have come to the fore: Abderrahmane Sissako (Life on Earth – 1998, Heremakono – 2002, Bamako – 2006), Mahamat-Saleh Haroun (Abouna – 2002, Daratt – 2006, A Screaming Man – 2011- Chad), Flora Gomes (Po di Sangui – 1996, Nha Fala – 2002) and Newton Aduaka (Ezra – 2007- Nigeria). Meanwhile, Sembène Ousmane achieved a brilliant coda to his career with Moolaadé (2004). These key works nonetheless remain shining exceptions in an impoverished cinematographic landscape characterised by lack of commitment from African funders or states towards their filmmakers and producers. Will new digital productions lead to a long hoped-for renaissance? This seems unlikely in the near future, but then, Africa has always had an astonishing ability to surprise us!

Po di Sangui, Flora Gomes, 1996

Daratt, Mahamat Saleh Haroun, 2006

Bamako, Abderrahmane Sissako, 2006

_______________________________________

(1) : Jean Rouch was the one who “discovered” Oumarou Ganda in I, a Negro (1958) and encouraged him (as he did a number of African filmmakers) to make his own films. Far from “viewing Africans as insects”, Jean Rouch knew how to combine an ethnologist’s values with the aesthetic demands of an accomplished film director. As a humanist, he showed respect for others as well as for himself.

> DOWNLOAD A PDF OF THE ARTICLE

* Jean-Pierre Garcia is Editor of Le Film Africain & du Sud magazine.

The Festival de Cannes would like to thank the authors for cntributing for free.