THE HISTORY OF RUSSIAN CINEMA

BY JOEL CHAPRON *

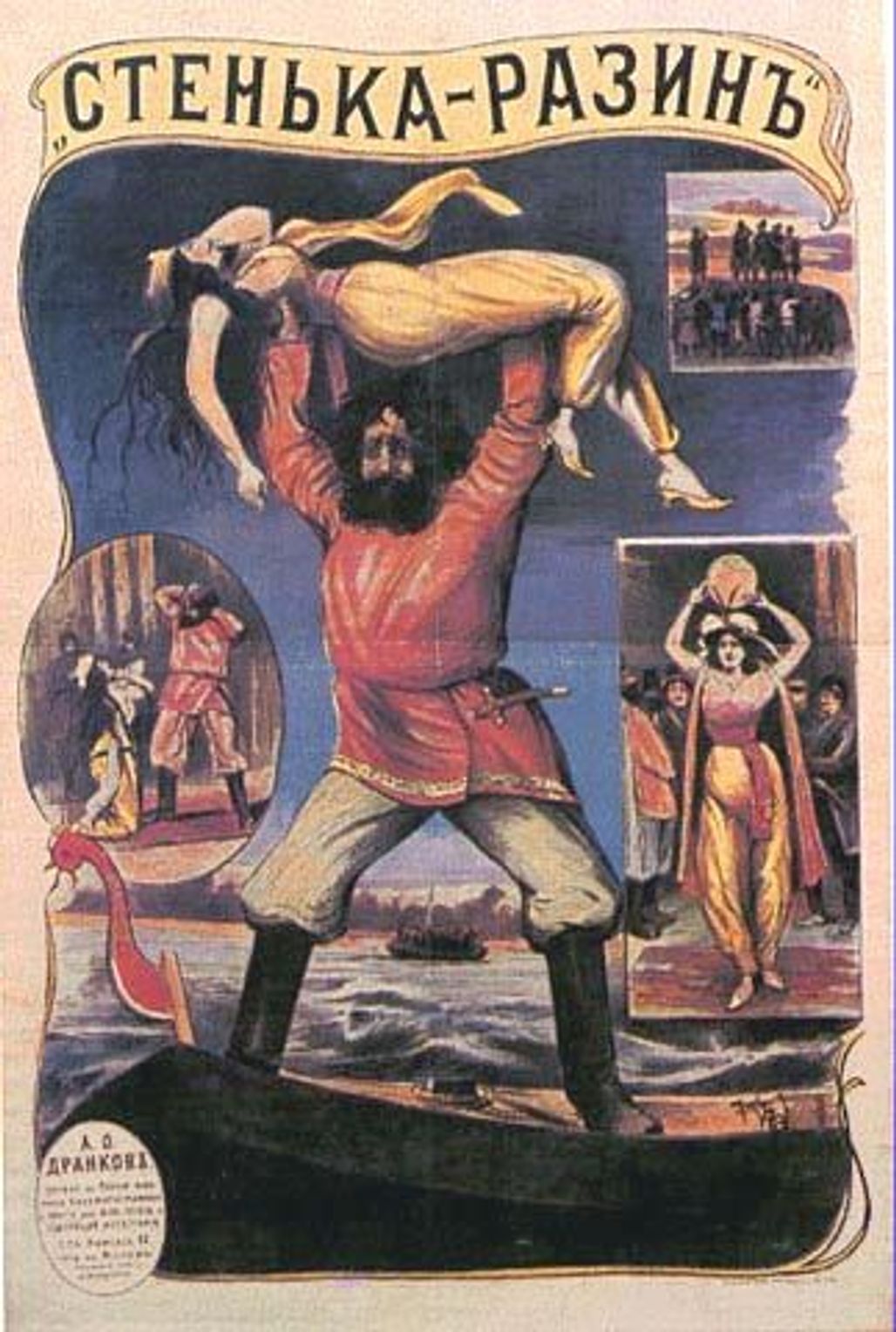

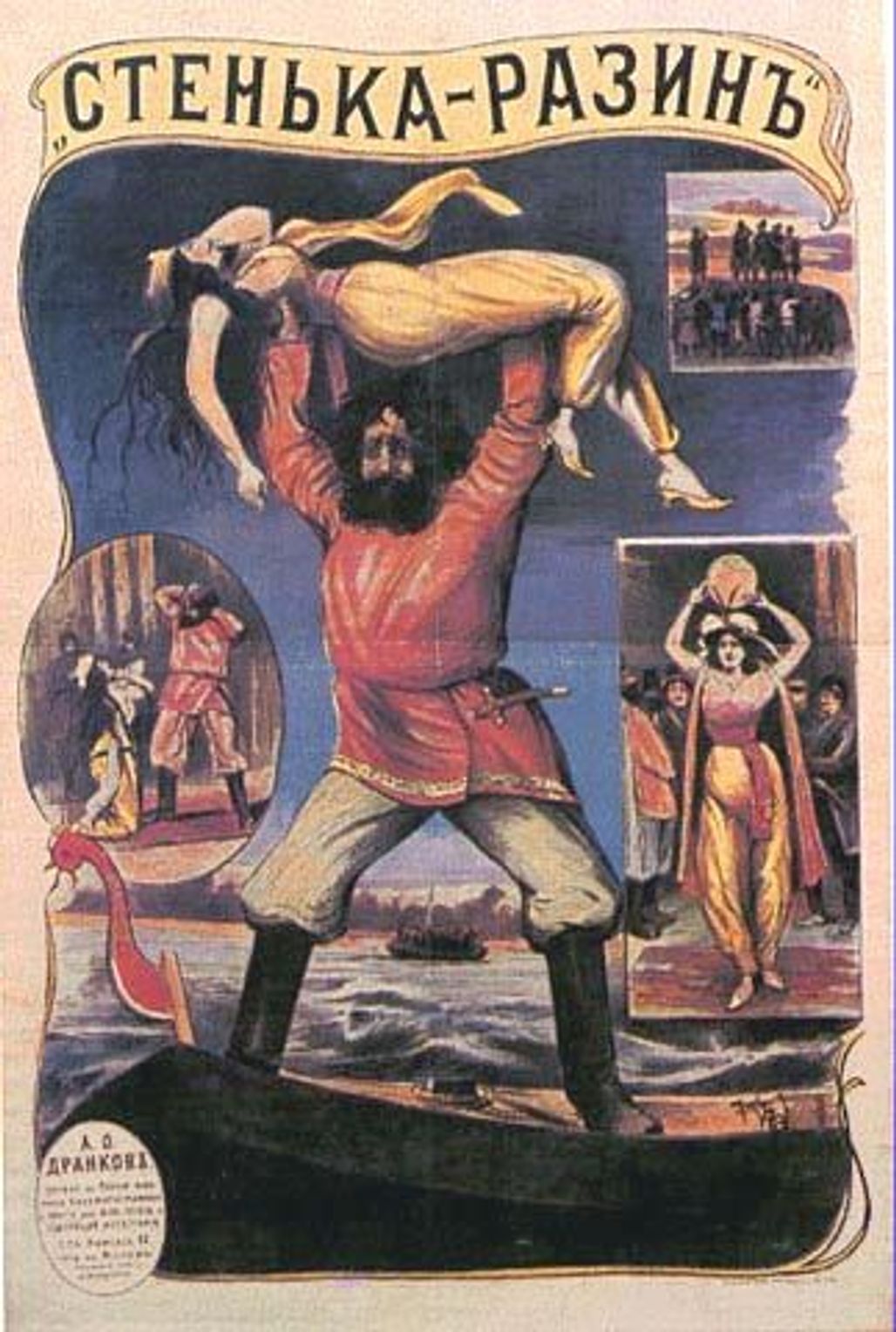

The first Russian fiction film, Stenka Razine by Drankov, dates back to 1908. By 1913, Russia already had 1,400 cinemas and had produced around a hundred films. From 1914, the Tsarist regime began making propaganda films. Protazanov, Gardin and Mozzhukhin enjoyed remarkable careers during the years of conflict.

The Revolution in 1917 brought disarray to the film sector. Many filmmakers emigrated (Ermolieff, Mozzhukhin, Protazanov – who later returned). In 1919, the film industry was nationalised and the world’s first film school (the VGIK) was created. Film became the main vector of communication, education and propaganda. In 1922, Lenin relaxed his grip and re-established a private film industry that was to give birth to the works of Barnet, Protazanov and Pudovkin. The state cinema produced Eisenstein’s Strike. From Eisenstein’s The Battleship Potemkin to Abram Room’s Bed and Sofa, avant-garde films and documentaries (Vertov) were produced alongside more traditional films on historic themes or dealing with everyday life. The great theories on editing were developed during this period.

|

|

|

| Strike directed by Eisenstein | Bed and Sofa directed by Abram Room |

|

|

The Battleship Potemkin directed by Sergueï Eisenstein

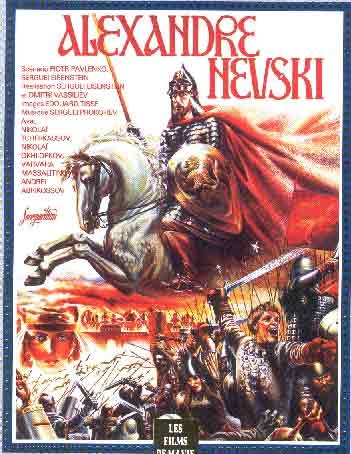

From the end of the 1920s, the film industry was affected by the tightening of Stalin’s ideological grip and avant-garde cinema (Kouleshov, Vertov, Eisenstein) was condemned as “elitist”. In 1932-1934, film production was subjected to the dogma of Socialist Realism, although the Hollywood model was admired. The 1930s were marked by musicals (Alexandrov, Pyriev), “psychological” films (Donskoy), films about ordinary life (Trauberg and Kozintsev) and epics. After the great Stalinist purges, the film industry saw a popular revival of films about historic figures that exalted patriotism (Petrov’s Peter the Great, Eisenstein’s Alexander Nevsky, Pudovkin’s Souvorov) in the face of a rising tide of various forms of fascism. However, the war revived documentaries (Donskoy, Vertov, Dovzhenko). The post-war period veered towards the cult of Stalinism (Chiaureli’s The Fall of Berlin), while the number of films was in decline.

|

Alexander Nevsky directed by Eisenstein

Production took off again with the advent of “the thaw” (1955-1956), when restrictions were relaxed and the individual was once again at the centre of filmmakers’ preoccupations. Upon their return from the war, Chukhrai (Ballad of a Soldier), Bondarchuk (Destiny of a Man) and Ozerov (Liberation) depicted the tribulations that had been suffered. In 1958, Kalatozov was singled out to receive the Palme d’Or in Cannes for The Cranes are Flying. In spite of ideological obstacles — with sanctions ranging from being summoned to the Kremlin (Khutsiev for I am Twenty) to a ban on filmmaking (Askoldov for Commissar), as well as re-editing, cuts, changes to the dialogue, delayed releases, the banning of festivals, censorship of the credits, and so forth — Tarkovsky, Konchalovsky, Paradzhanov, Guerman, Muratova, Chepitko, Okeev, Mikhalkov, Klimov, Panfilov, Iosseliani, Khamraev and Norstein, all earned their places in the pantheon of the 1960s and 1970s (although some of their films were not discovered until after the Perestroika). At the turn of the 1970s, the gap widened between the image that the Soviets held of their cinema (as a popular art form) and the way it was perceived by the Western world (as a demanding auteur genre). In foreign film festivals, the favoured Soviet films were those made by directors who ran into problems with censors, reflecting the degradation of the USSR’s image. Even today, contemporary Russian cinema still suffers from this dualism.

Production took off again with the advent of “the thaw” (1955-1956), when restrictions were relaxed and the individual was once again at the centre of filmmakers’ preoccupations. Upon their return from the war, Chukhrai (Ballad of a Soldier), Bondarchuk (Destiny of a Man) and Ozerov (Liberation) depicted the tribulations that had been suffered. In 1958, Kalatozov was singled out to receive the Palme d’Or in Cannes for The Cranes are Flying. In spite of ideological obstacles — with sanctions ranging from being summoned to the Kremlin (Khutsiev for I am Twenty) to a ban on filmmaking (Askoldov for Commissar), as well as re-editing, cuts, changes to the dialogue, delayed releases, the banning of festivals, censorship of the credits, and so forth — Tarkovsky, Konchalovsky, Paradzhanov, Guerman, Muratova, Chepitko, Okeev, Mikhalkov, Klimov, Panfilov, Iosseliani, Khamraev and Norstein, all earned their places in the pantheon of the 1960s and 1970s (although some of their films were not discovered until after the Perestroika). At the turn of the 1970s, the gap widened between the image that the Soviets held of their cinema (as a popular art form) and the way it was perceived by the Western world (as a demanding auteur genre). In foreign film festivals, the favoured Soviet films were those made by directors who ran into problems with censors, reflecting the degradation of the USSR’s image. Even today, contemporary Russian cinema still suffers from this dualism.

Ballad of a Soldier directed by Tchoukhraï

The Perestroika changed the whole picture. In 1986, the Union of Filmmakers pushed the old guard aside and made room for the reformers. Pichul (Little Vera), Podniek (Is it Easy to be Young?), Abouladze (Repentance), Sokurov (The Lonely Voice of Man) and Shakhnazarov (Zero City) showed images that had previously been forbidden and addressed themes that had long been taboo (drugs,  sex, the Gulag, poverty, Stalinism, vulgar language, etc.), conferring a new image on Russian cinema. In 1990-1991 (with the dissolution of the USSR), Lounguine (Taxi Blues), Kanevski (Freeze, Die, Come to Life), and Bobrova (Hey, You Geese) reflected the social collapse. The 1990s were deeply rooted in this trend, even though “money-laundering films” abounded. However, the disorganisation of the system prevented these filmmakers from being screened publicly. Thanks to co-productions (mainly with France), directors like Mikhalkov (Burnt by the Sun), Guerman (Khrustalyov, My Car!), Dykhovitchny (Moscow Parade), Todorovski (Katia Ismailova) and Sokurov (Russian Arc) managed nevertheless to make films.

sex, the Gulag, poverty, Stalinism, vulgar language, etc.), conferring a new image on Russian cinema. In 1990-1991 (with the dissolution of the USSR), Lounguine (Taxi Blues), Kanevski (Freeze, Die, Come to Life), and Bobrova (Hey, You Geese) reflected the social collapse. The 1990s were deeply rooted in this trend, even though “money-laundering films” abounded. However, the disorganisation of the system prevented these filmmakers from being screened publicly. Thanks to co-productions (mainly with France), directors like Mikhalkov (Burnt by the Sun), Guerman (Khrustalyov, My Car!), Dykhovitchny (Moscow Parade), Todorovski (Katia Ismailova) and Sokurov (Russian Arc) managed nevertheless to make films.

Nikita Mikhalkov’s signature

Nikita Mikhalkov’s signature

The revival dates from 2004, with the release of the first blockbuster, Night Watch (Bekmambetov), promoted by televised publicity. Since then, comedies and action films have been generating a national market share of 15% to 25%, while the auteur films continue to be celebrated at festivals, especially since Zviaguintsev carried off the Lion d’Or for The Return (Venice, 2003).

READ >>> CANNES AND RUSSIA: WITH LOVE OR WITHOUT

* Joel Chapron works as a Russian interpreter and foreign correspondant at the Festival de Cannes. He is in charge of Central and Eastern European countries at Unifrance, Associate Lecturer at the University of Avignon, author of numerous articles on Eastern European cinema and editor of the new edition of the Dictionary of Film (Larousse).

The Festival de Cannes would like to thank all the writers for their free contributions.

PHOTOS AND DRAWINGS BY SERGUEI EISENSTEIN: