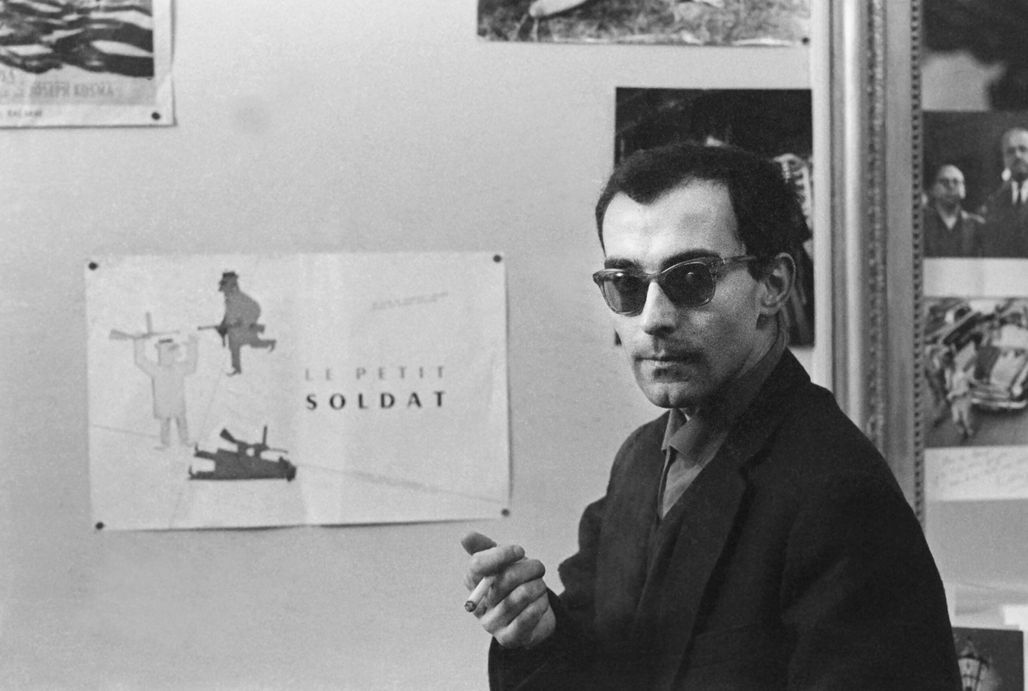

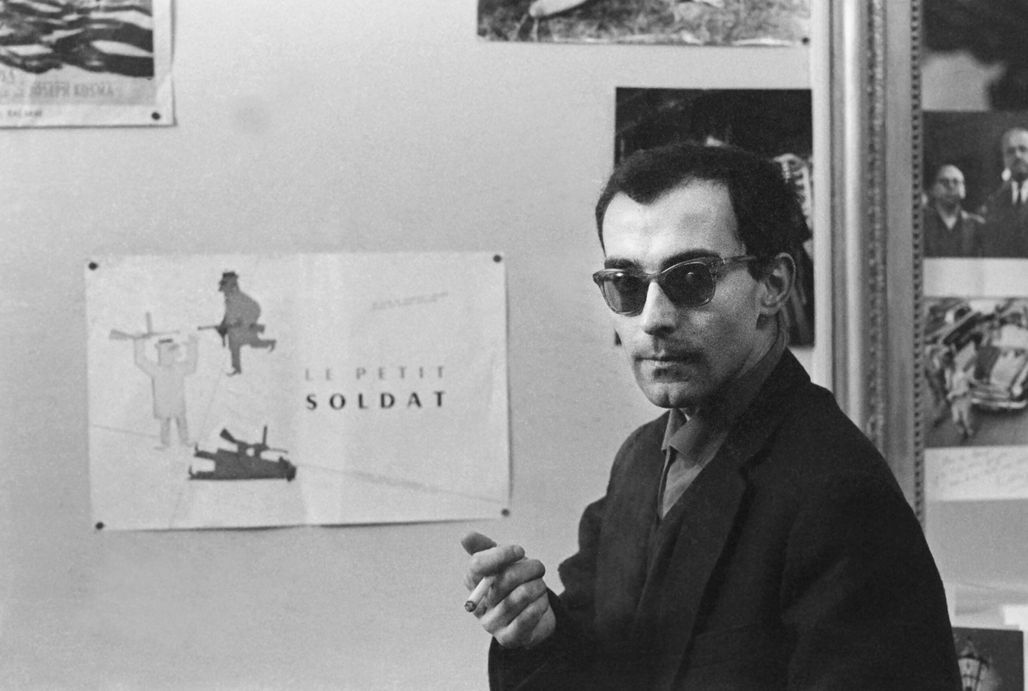

Godard par Godard (Godard by Godard), in the mind of a trailblazer of cinema

In Godard par Godard (Godard by Godard), Florence Platarets examines the career of Jean-Luc Godard without voice-overs or talking heads, letting him speak through a whole host of archives. The journalist and director of the Cinémathèque française, Frédéric Bonnaud, who wrote the documentary, looks back on its origins and on the way the New Wave director cleared the way for cinema.

How did the idea for this documentary come to you?

With Florence Platarets, we had directed a film on the New Wave and more specifically on the group of filmmakers who collaborated with Cahiers du cinéma: Truffaut, Rivette, Chabrol, Rohmer and Godard. We wanted to go further with one of them and it was Jean-Luc Godard who interested us the most. Godard literally spent his life giving interviews. The Godard cloistered away in Rolle, who didn’t want to see anyone, that was at the very end of his life. But before that, for fifty years, he did not cease to talk with journalists. He was someone who, with his own work and his place in cinema history, was extremely precise, intelligent and invigorating. When we began the film, he was as lively as could be.

Where do the archives come from that you used?

In part from the INA. We knew that there were certain archives that existed and I had them in mind during the writing. I’m thinking particularly about the ORTF story about the shooting of Bande à Part (Band of Outsiders) with Anna Karina and Claude Brasseur. For the films, the main rights holders are Studiocanal and Gaumont. We were also delighted to ferret out some lesser-known archives from foreign television stations. So we had great beacons to structure the films.

“No one other than Godard demanded as much from cinema.”

What was your guiding line?

Our desire wasn’t to stop at the Godard of the sixties, close to Matisse, with big flat tints of colours, but to start with the Godard who was still struggling to be accepted and to continue on all the way to the edge of the 2000s.

How did he view his own filmography?

He considered À bout de Souffle (Breathless) (1960) as his first attempt and I believe, for him, there were more important films. I’m thinking of Vivre sa vie (1962) or Passion (1982), which allowed him to continue his investigations. Unlike most artists, he never made the same film twice. Godard was never someone who was at a standstill. No one other than him demanded as much from cinema. He had a way of being demanding to his own art that was unique. He had a need to explore all of cinema’s possibilities, both from a narrative and a documentary point of view. He was obsessed by the fact that one can think with cinema and that it can lend itself to all sorts of experimentation.

Serge Daney said of him that he was part of the secret factory of cinema. What do you think he brought to cinema?

A complete reappraisal. If Godard is so important, it’s because he did to cinema what Picasso did to painting. He’s someone who knew cinema and film history like the back of his hand but who, right from his first film, called everything into question. Truffaut said in our documentary that along with Citizen Kane (1941), À Bout de Souffle (Breathless) is the best debut film ever. It’s a film that profoundly and radically changed film writing itself. There was a before and after À bout de Souffle (Breathless).

An Ex Nihilo production, with the participation of France Télévisions and the CNC.